10. Heroes and Villains of Ancient Africa:The Nok and Bantu Cultures

- Zack Edwards

- Aug 15

- 28 min read

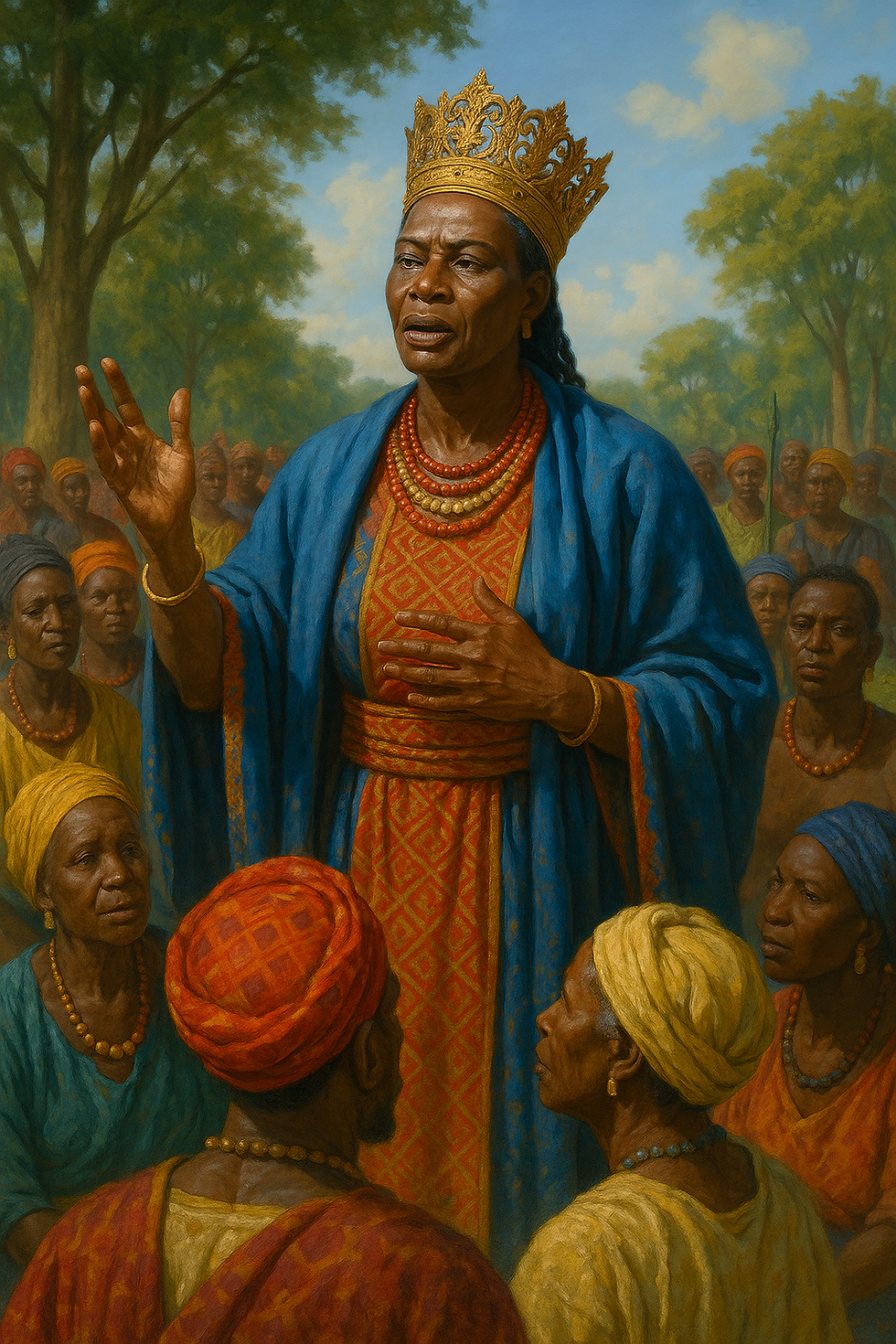

My Name is Mufwene: Elder Oral Historian (fictional composite figure)

My name is Mufwene, and I was born on the shores of a great lake whose waters stretch farther than the eye can see. From the moment I could walk, I was surrounded by voices—elders telling the tales of our ancestors, parents teaching the wisdom of the land, and fishermen singing to the rhythm of their paddles. My earliest memories are of sitting by the fire at night, my head resting on my mother’s knee, as my grandfather’s deep voice carried the stories of our people across the glowing embers.

Keeper of the Word

When I grew older, I was chosen to apprentice under the oldest storyteller in our village. He taught me that words are not merely sounds; they are vessels that carry the past into the future. I learned to recite the journey of our Bantu ancestors—how they came from lands far to the northwest, bringing with them seeds, iron tools, and the knowledge to tame both field and forest. I memorized the names of clans, the rivers they followed, and the mountains they crossed. Each story was a map of who we are.

Witness to Change

As the seasons passed, I saw my people grow and change. New crops, like bananas and plantains, came to our gardens from distant lands, and our herds grew stronger with cattle that thrived in our grasslands. We traded salt, ivory, and iron for beads, cloth, and stories from faraway places. I came to understand that history is not only in the past—it is in the way we adapt and yet remain ourselves.

The Weight of Memory

Being an oral historian is a heavy responsibility. I do not write my words on bark or hide; I speak them into the minds of the young, trusting they will carry them forward. I teach them the customs of respect for elders, the rituals of planting and harvest, and the songs that call the spirits of our ancestors to bless the living. Without these, a people forget who they are, and a forgotten people can be swept away like sand in the wind.

Speaking to the Future

Now my hair is white, and my voice is slower, but still I gather the children under the old fig tree. I tell them of the first migrations, of the unity of our language, and of the lakes that have been our lifeblood. I tell them that one day they will sit where I sit, holding the firelight in their faces and the future in their words. As long as the stories are spoken, the people will endure.

Tongue of Our Ancestors: Origins and Spread of Bantu Languages – By Mufwene

Our words, the ones we speak today, were born in the lands of West and Central Africa. There, in fertile valleys and forests rich with game, our ancestors shaped the first sounds of what would become the Bantu languages. These words carried the heartbeat of our people—names for the rivers that fed us, the tools we used, the spirits we honored. They were the thread that tied the living to the living, and the living to the dead.

Why We Left Our Homeland

In the time of the great migrations, our people faced changes that could not be ignored. The land grew crowded, and some fields no longer yielded the harvests they once did. Herds needed more grazing land, and our hunters sought new forests where game still roamed in plenty. We carried seeds of yam, millet, and later the banana, along with the skill to work iron, knowing these would sustain us wherever we went. The need for land, the pull of trade, and the call of opportunity set our feet upon long and winding paths.

The Journey Across the Continent

From the cradle of our speech, families began to move eastward and southward. They followed rivers, skirted mountain ranges, and crossed wide grasslands. Some settled near great lakes, others in forests where the trees grew thick and tall. Along the way, our words traveled with us, branching and changing like the rivers we crossed. New dialects were born, shaped by the songs, tools, and customs of the lands where we paused to make our homes.

Bringing More Than Words

We carried more than our language. We brought with us the knowledge of farming, planting in rows that turned wild land into gardens. We knew how to smelt iron, forging blades that cut deeper than stone could manage. We brought music, stories, and a way of life that honored our elders and kept our ancestors close in our thoughts. Everywhere we went, we traded and learned from the people we met, sometimes blending our ways with theirs, sometimes teaching them ours.

The Legacy of the Journey

Today, the Bantu languages are spoken across a vast part of Africa, from the equator down to the southern seas. Though the words have shifted and taken on new sounds, they still hold the shape of that ancient tongue. When I speak, I feel the weight of the journey in every syllable, as if my voice walks the same trails my ancestors once traveled. It is not just language—it is the map of our history and the proof that we are many peoples bound by a single, living thread.

My Name is Dagan: Ancestral Nok Artisan (fictional composite figure)

The earth here is red, rich, and alive with clay that shapes our homes and our art. My father was a farmer, my mother a potter, and from them I learned that the land is not just where we live—it is what gives us life. As a boy, I would sit for hours watching the elders mold figures from the clay, each one telling a story of our people and the spirits who walk among us.

Learning the Craft

When I was old enough to shape my own hands around a lump of clay, I began my training with the master artisans of our community. They taught me how to mix the earth with water until it was just right, how to carve the details that would give life to eyes and mouths, and how to fire the figures in the open kiln so the clay would harden like stone. Every sculpture had meaning—some to honor our ancestors, others to protect our homes, and a few to mark important events in our lives.

Iron and Transformation

Not long after I became skilled in my craft, our village saw a great change. Men from nearby settlements brought knowledge of working with iron. They showed us how to heat stone until it released a red-hot heart, which we could shape into tools and weapons stronger than any before. I took pride in making clay molds for their smelting furnaces and decorating them with patterns that told our story. The iron changed our farming, our hunting, and even our defense against those who might threaten us.

Life in the Village

Our days followed the rhythm of the seasons. In the wet months, the fields came alive with millet and yams, and in the dry months, we traded with neighbors for salt, beads, and oil. My work was never done; there was always another figure to make, another story to tell in the hardened curves of clay. Children would watch me work, their eyes wide, and I would tell them of the people before us, the migrations, and how we came to live between the hills and rivers.

Legacy in Clay

I do not know if my name will be remembered, but I know my hands have left a mark. The figures I have made will outlast my bones, resting in the earth until they are found by people I will never meet. They will know, even without my voice, that we were a people who shaped our world with both our hands and our hearts, and that art was our way of speaking to the future.

The Shape of Our Homes: Daily Life and Society in Nok Culture – Told by Dagan

Our homes rise from the earth itself, built from clay mixed with water and straw, shaped into walls that dry strong under the sun. The roofs are thatched with tall grasses, sloping to keep the rains from pooling. We build in clusters, each family’s home near the next, with open spaces where children play and elders gather to talk. The fire pits glow at night, and their smoke rises like prayers to the sky.

The Heart of Our Society

In our village, everyone has a place. Families work together, but our roles are clear. The elders guide us with wisdom, settling disputes and keeping the traditions alive. Warriors guard the village from raiders and wild animals. Farmers feed us all, tending the fields and bringing in the harvest. Traders travel to other settlements, carrying goods and stories. Artisans like me give shape to clay and help the spirit of our people take form in terracotta. Every person’s work is a thread in the cloth of our lives.

The Farmers and the Fields

The farmers are the lifeblood of our society. They plant yams, millet, and oil seeds in rows that turn the red earth green. In the wet season, the fields swell with life, and in the dry season, we store what we can in clay jars to feed us through leaner times. Farmers also keep goats and chickens, adding meat and eggs to our meals. Their skill in growing food allows others, like me, to spend more time on craft and trade.

Trade Beyond Our Horizon

Our people do not live alone in the world. Traders walk paths that wind far beyond our hills, bringing back salt from the far north, beads and cloth from distant markets, and stories from lands most of us will never see. We give in return what we have—iron tools forged from smelted ore, terracotta figures, and foodstuffs. Trade binds us to other peoples, bringing wealth and ideas that shape our ways.

The Artisans’ Place

As an artisan, my work is both practical and sacred. I shape clay into figures that stand in our homes, protect our families, and honor our ancestors. I craft pots for storage, vessels for cooking, and ornaments to mark important moments. In our society, artisans are respected for keeping the spirit of our people alive in our creations. Our work will remain long after our bodies are gone, speaking silently to those who will follow.

Choosing the Earth: Nok Terracotta Sculptures and Artistic Expression – By Dagan

When I speak of our terracotta sculptures, I speak of the heart of my craft. It begins with the earth itself. We search for clay that is smooth and strong, the kind that will hold together when shaped and will not crack under the sun’s fire. The best clay lies beneath the surface, where roots do not reach. We dig it out with care, for it is a gift from the land, and we must treat it with respect.

Shaping the Form

Once the clay is ready, I knead it until it is soft and free of stones. My hands then guide it into shape, sometimes building the figure from a single solid form, other times crafting separate pieces and joining them carefully. Each feature is placed with purpose. Large eyes to see beyond this world, patterned hairstyles to show beauty and status, and hands positioned to speak silently of the figure’s role. Some pieces are full figures, others only heads, but all are alive in their own way before the firing ever begins.

The Fire’s Trial

When the figure is complete, it must face the fire. We place it in an open pit kiln, covering it with wood and grass. The flames must burn hot enough to harden the clay but not so fierce that it cracks. As the smoke rises, I whisper to the spirit I have shaped, asking it to be strong for the generations to come. When the fire cools, the sculpture emerges hardened, ready to stand guard over the living.

The Language of Symbols

Every line, pattern, and curve in our art holds meaning. Scarification marks carved into the face tell of clan, honor, or life’s trials. Jewelry and hair designs speak of wealth or beauty. Some figures hold objects—tools, weapons, or bowls—hinting at their role in life or the spirit world. Our people can read these symbols as easily as words, knowing the story of a sculpture without a voice.

The Spirit Within

To us, a terracotta figure is more than clay. It is a vessel that connects the living to the ancestors. Some protect the household from harm, others guide the spirits of the departed, and some stand as offerings to the forces that govern the earth and sky. When I finish a sculpture, I do not see only the clay. I see the presence of those who came before, standing with us still, reminding us of who we are.

The Coming of Iron: Iron Smelting and Technological Advances – Told by Dagan

It was as if the earth itself had given us a secret. Before this, our blades were stone and our tools were bone or wood. They served us well, but iron brought a strength we had never known. The knowledge came to us through travelers and traders, and once we learned its ways, our lives began to change.

Finding the Ore

The first step is to find the right stone. We search the hills and riverbeds for the heavy, reddish rock that hides the iron within. It is carried back to the village in baskets, each piece a promise of sharper tools and stronger weapons. This stone is not ready to use—it must be transformed by fire.

The Furnace’s Heart

We build our furnaces from clay, shaping tall, narrow towers with an opening at the base for air and a mouth at the top for feeding the fire. Charcoal fills the furnace, layered with pieces of ore. When the fire is lit, we use bellows made from animal hides to breathe life into the flames. The heat grows fierce, hot enough to force the earth to release its metal. Hours pass, and the rock begins to soften, separating into slag and the bloom of iron at the furnace’s core.

Shaping the Metal

When the bloom is ready, it is taken from the furnace and hammered to drive out the impurities. The blacksmith shapes it into blades, spear points, and farming tools. Iron knives cut cleaner, iron hoes dig deeper, and iron-tipped spears strike harder. What once took days of labor can now be done in hours, and what once was fragile is now enduring.

The Journey of Knowledge

This skill did not stay with us alone. Traders and migrants carried it to far-off lands. The Bantu-speaking peoples took iron with them as they moved east and south, teaching others how to build furnaces and forge strong tools. In this way, the gift of iron spread across the continent, changing how people farmed, hunted, and defended their homes. I take pride knowing that what began in our hands now strengthens the lives of many.

The First Gardens: Agricultural Innovations of Bantu Peoples – Told by Mufwene

Long ago, when our ancestors still lived in the western and central regions of Africa, they learned to tame the soil. They planted yams, their vines curling across the earth, their roots swelling with food enough to feed a family for many days. Millet too became a trusted crop, its golden heads rising above the fields, easy to store and grind into flour that could last through the dry season.

The Coming of New Crops

As our people journeyed eastward, the paths they walked brought them into contact with traders from distant lands. From these exchanges came the banana and the plantain, plants that grew tall and green, their broad leaves whispering in the wind. They flourished in wetter climates, and unlike yams or millet, they could bear fruit many times in a single year. This meant fewer times of hunger and more stability for our villages.

Changing the Rhythm of Life

With these crops, our farming changed. Yams filled the stores for the dry months, millet gave bread to our tables, and bananas and plantains offered fresh food when other fields were bare. This abundance allowed our people to settle for longer in one place, no longer moving so often to find new land. Villages grew larger, and families had more children who could survive to adulthood.

The Growth of Our People

As food became more plentiful, our numbers increased. Fields stretched farther from the center of the village, and new clearings were made for farming. More mouths to feed also meant more hands to work. Young men and women cleared new land, planted seeds, and tended the crops, while the elders taught the old ways and preserved our stories. Our settlements became permanent homes rather than temporary camps.

The Legacy of the Fields

The knowledge of yam mounds, millet rows, and banana groves traveled with us as we spread across the continent. Wherever the Bantu tongue was heard, fields soon followed, and with them, the hum of life—children laughing, women pounding grain, and fires crackling at night. Agriculture gave us the power to root ourselves in the land, and in doing so, it gave us a future that stretched far beyond the horizon.

Cultural Beliefs, Spiritual Practices, and Ancestral Worship – Told by Mufwene

I will speak of the ways our people walk between the living and the spirits. To the Bantu-speaking peoples, the world is more than what the eyes can see. There is the world of the living, the world of the ancestors, and the realm of the spirits who guide the wind, the rain, and the growth of the crops. We believe these worlds are bound together, and what we do in one can stir the other.

The Place of the Ancestors

Our ancestors are never truly gone. When a person dies, their body returns to the earth, but their spirit remains close, watching over the living. We honor them with offerings of food, drink, and sometimes the first fruits of the harvest. Their names are spoken in prayers so they will not be forgotten, for a forgotten ancestor cannot protect their family. Before any great decision, we seek their blessing, asking for wisdom through dreams, visions, or the words of a diviner.

Rituals and Ceremonies

Across our many lands, though our languages and customs differ, there are rituals we share. We gather for rites of passage when a child is born, when they become an adult, and when they marry. At planting season, we call upon the spirits of the land to bring rain and fertility to the soil. Drumming, singing, and dancing are not merely for joy—they are ways to speak to the unseen, to open a path between worlds. Fire and smoke carry our messages upward, and water is used to cleanse and bless.

The Role of Spiritual Guides

Among us are those who know how to speak more closely with the spirits. Some are healers, using herbs and roots given by the earth. Others are diviners, who read the patterns in bones, shells, or the movement of water to understand the will of the ancestors. Their role is not only to cure illness but to mend what is broken between the living and the spirit world.

The Strength of Belief

These practices have endured as our people have moved across the continent. Even when new beliefs arrived from distant lands, the respect for our ancestors remained. To this day, when I sit under the great fig tree and tell the stories of our past, I feel my own forefathers beside me. Their presence is in the words I speak, the breath I take, and the firelight on my face. As long as we remember them, we are never alone.

Reasons for the Impact of Bantu Migrations on Indigenous Peoples – By Mufwene

I will tell of the time when our Bantu-speaking ancestors met others who had walked the land long before us. These were the hunter-gatherers, people of the forests, rivers, and plains, who lived by the rhythm of the hunt and the gathering of fruits and roots. When the first Bantu families came into their territories, the meetings were not always peaceful. Our new ways—farming, ironworking, and permanent villages—changed the balance of life.

The Strength of Farming and Iron

The Bantu brought fields of yams, millet, and later bananas, along with iron tools that could clear forests and turn soil more quickly than stone or bone implements. With these, they could produce more food and settle in larger groups. This abundance made it easier to survive hard seasons, but it also meant the Bantu could occupy more land. For hunter-gatherers, who moved with the seasons, this narrowing of space brought hardship.

Displacement and Absorption

In some places, the hunter-gatherers were pushed farther into the deep forests or drier lands where farming was harder. In other places, they joined with the Bantu, learning new ways while sharing their knowledge of the land. Over generations, many of these smaller groups were absorbed into the Bantu-speaking communities. Their languages faded, and their customs were blended into the new life of the village.

The Loss of Old Ways

When a people leave behind their language, their stories become harder to tell. When their rituals are no longer practiced, the link to their ancestors grows thin. For some hunter-gatherer communities, the arrival of the Bantu meant not only a change in how they lived, but a loss of the identity that had been shaped over countless generations. The land, once shared, now had new borders set by fields and fences.

A Thread That Still Remains

Yet even in the places where the old ways seemed to disappear, pieces of them remained. Certain hunting songs, healing practices, and knowledge of wild plants still live in Bantu traditions today. The meeting of peoples brought loss, but it also brought exchange. It is for us to remember that our history is not only about those who brought change, but also about those who received it, shaping who we have become.

My Name is Queen Nzinga Mbande (1583–1663): Queen of Ndongo

I was born in 1583 in the Kingdom of Ndongo, in the land that is now Angola. My father, King Kiluanji, was a ruler who understood the delicate balance between war and diplomacy. From a young age, I watched him lead councils, settle disputes, and guard our people against the ever-growing threat of Portuguese intrusion. My mother, though not of royal blood, was wise and proud, and she taught me the values of strength and cunning. I learned to speak several languages, including Portuguese, and mastered the art of negotiation alongside my understanding of the spear.

Rise to Power

When my brother, King Mbande, came to the throne, I became one of his most trusted advisors. The Portuguese were pressing into our lands, demanding tribute, slaves, and control over our trade routes. My brother sent me to negotiate peace in 1622, and I went to Luanda determined to show that we were equals, not subjects. In that meeting, I famously refused to sit lower than the Portuguese governor. Since he offered no chair, I ordered one of my attendants to kneel so I could sit upon his back, showing that Ndongo would bow to no one.

Defending My People

After my brother’s death, I became queen in 1624, and I ruled both Ndongo and later Matamba. The Portuguese sought to control our lands through war and alliances with rival tribes. I used every tool I had—battle, diplomacy, and strategic marriages—to strengthen my position. I formed alliances with former enemies, welcomed runaway slaves and soldiers into my army, and used my knowledge of European politics to play my rivals against each other.

The Warrior Queen

I was not content to lead from behind palace walls. I dressed in armor, rode into battle with my troops, and devised tactics that confounded my enemies. For nearly forty years, I resisted Portuguese domination. I moved my capital when necessary, employed guerrilla warfare, and created trade agreements that kept my people supplied. My armies were feared not only for their skill but for their determination never to yield.

Later Years and Legacy

In my final years, I turned my focus toward building stability. I reestablished diplomatic ties with the Portuguese when it served my people’s future, secured our trade routes, and worked to promote Christianity in a way that blended with our traditions. When I died in 1663, I left behind a kingdom still standing strong against colonial rule. My name became a symbol of resistance and leadership for generations to come, a reminder that a woman could rule as fiercely as any man and protect her people with wisdom and strength.

Women’s Power: Women’s Roles & Leadership in Bantu Societies – Told by Nzinga

Though I ruled in a time far from the first Bantu migrations, the ways of my people were shaped by those who came before us. Among the Bantu-speaking societies, women have long held places of influence. They were not only mothers and keepers of the household but advisers, mediators, and in some places, chiefs. A woman’s wisdom was sought in council, for she knew the rhythms of the land, the needs of the family, and the balance that must be kept in the community.

Mothers of the Land

In many Bantu traditions, land and farming passed through the mother’s line. Women guarded the seeds from one harvest to the next and decided when planting would begin. They oversaw the division of fields and the sharing of food, ensuring no family went hungry. This control over the means of life gave them a voice in the affairs of the village, for without their agreement, no great change could take root.

Voices in the Council

Elders tell that in ancient times, village councils often included respected women who spoke for the clans. They were skilled in settling disputes, forging alliances, and advising on matters of trade or war. Their words carried weight because they were seen as protectors of life and harmony. It was understood that to ignore the counsel of such women was to risk the stability of the whole community.

My Own Throne

When I came to rule Ndongo and Matamba, I drew upon this tradition. I sat in council beside men, but I did not come to agree blindly. I spoke as my foremothers had, with the authority of one who knows the strength of her people and the cost of their survival. I negotiated treaties, commanded armies, and made decisions that shaped the fate of my kingdoms. I did not stand apart from the ways of my ancestors—I continued them.

The Thread Through Time

From the women who first guided the planting of millet and yams to those who today lead in government and community, there is a thread that connects us. Leadership is not given by chance; it is earned through service, wisdom, and courage. My life was built upon the foundation they laid, and I hope that my rule added another stone to the path for those who will follow.

Lifeblood of the People: Trade Networks & Cultural Exchange – Told by Nzinga

I have seen how the movement of goods shapes the strength of a kingdom. Long before my time, the Bantu-speaking peoples built paths across forests, rivers, and plains, linking village to village and people to people. These trade routes were not just lines on the land—they were the veins through which life flowed, carrying food, tools, and ideas from one region to another.

From the Fields to the Market

Inland farmers grew yams, millet, and later maize and bananas, filling their granaries with enough to feed their families and still have more to trade. They brought their harvests to market, where they exchanged them for salt, beads, cloth, and iron tools. These goods might pass through many hands before reaching the coast, but each exchange bound the traders together in trust and obligation.

Bridging Inland and Coast

Those who lived closer to the great rivers or the ocean became the bridge between inland villages and distant markets. Caravans carried ivory, copper, and iron from the interior to the coastal towns, where merchants from faraway lands came to trade. In return came items rare to the inland peoples—fine textiles, glass beads, and in later times, firearms. The coast was the meeting place of worlds, and it was there that goods, languages, and customs blended.

The Exchange of Culture

Trade carried more than objects. Songs, stories, and beliefs traveled alongside the goods, weaving the cultures of different Bantu-speaking communities together. Marriage alliances often followed trade agreements, joining families from distant lands. Techniques for farming, ironworking, and craft-making spread as easily as language, strengthening the bonds between people who might never have met face to face.

The Strength in Connection

In my own rule, I saw the power of these networks. I forged alliances through trade, ensuring that my people had access to weapons and resources to defend our land. I knew that controlling the flow of goods meant controlling the balance of power. Just as it was for my ancestors, trade in my time was not simply about wealth—it was about survival, influence, and the weaving of ties that could hold a people together for generations.

Reasons for the Decline or Disappearance of Nok Civilization – Told by Dagan

I have seen the Nok people at their height—fields full, furnaces burning, and markets alive with trade. Yet even as I shaped clay and worked beside the smiths, there were signs that our way of life might not last. By the time the elders told their last stories of my generation, the fires in some villages had grown cold, and the sound of the hammer on iron had faded into silence.

The Hunger of the Earth

Our land was generous, but it could also grow weary. Year after year, we planted in the same soil. The yams and millet no longer grew as tall, and harvests became smaller. The earth that had once given so freely began to crack in the dry season and wash away in the rains. Some say this was because we did not let the land rest, and without new farming knowledge, our fields could not keep pace with the mouths they had to feed.

The Sky Turns Against Us

There are those who remember when the rains became uncertain. In some years they came late or not at all, and in others they fell so heavily that crops rotted in the fields. The rivers changed their courses, and hunting grew harder. When the skies do not give what is needed, even the strongest community must decide whether to stay or to seek better fortune elsewhere.

The Call to Move

Many families chose to leave. Some went south toward greener lands, others east toward trade routes that promised survival. Those who left took with them their skills and their language, joining with other peoples along the way. Over time, the villages they left behind emptied, and the once-busy paths grew over with grass.

What Remains

I do not know if the Nok truly ended or if we simply became part of other peoples. Our art, our iron, and our ways of living may still breathe in their hands. But here, in the land where I once shaped the clay, the voices of my people are quiet. What remains is buried beneath the earth, waiting for someone in another time to uncover our story and wonder where we went.

My Name is Cheikh Anta Diop (1923–1986): Historian, Anthropologist, and Scientist

I was born in 1923 in the village of Thieytou, in Senegal. My childhood was shaped by the rhythms of rural life and the wisdom of elders who still carried the memory of a time before colonial rule. From an early age, I asked questions—about where our people came from, about the connections between African cultures, and about why our history was often told by others in ways that diminished us. My curiosity was a fire that would never be put out.

Journey to France

In 1946, I traveled to Paris to continue my studies. I intended at first to study mathematics and physics, but I soon turned to history and anthropology, believing that understanding our past was just as important as mastering the sciences. In Paris, I saw how African history was often misrepresented or ignored altogether. I began to devote my life to showing that Africa had a deep and rich civilization long before colonial contact, one that had influenced the wider world.

Research and Resistance

My work focused on proving that ancient Egypt was an African civilization and that the cultural unity of Africa could be traced through language, art, and traditions. This was not a popular position at the time, and I faced resistance from those who saw Africa as a place without a history. I used linguistics to link the languages of West Africa with those spoken in the Nile Valley. I turned to archaeology, carbon dating, and historical texts to make the case that Africa’s contributions to science, art, and governance were undeniable.

Advocate for African Unity

I believed that history was not just something to be studied—it was a tool for liberation. I spoke and wrote about the need for African nations to unite politically and economically, just as they had once been connected culturally. I argued that if Africans knew the truth about their past, they would see themselves not as divided colonies but as heirs to a shared and powerful heritage.

Lasting Legacy

I continued my research, teaching, and writing until my death in 1986. My books challenged the world to rethink African history and inspired generations of African scholars to take ownership of their story. I leave behind the belief that history is not merely about the past—it is the foundation upon which we build our future. If we know who we are and where we come from, we can stand tall among the nations of the earth.

Historical Links Between Ancient and Modern Identities – Told by DiopMy life’s work has been to show that the history of Africa is not a series of broken fragments but a continuous thread. When we look closely—at our languages, our customs, and even the patterns in our blood—we find clear links between the peoples of today and those who lived thousands of years ago. The Bantu and the Nok are not distant strangers to us; they are our ancestors, their legacy still living in our bodies and our words.

The Language ConnectionLanguages carry history as surely as rivers carry water. Across much of sub-Saharan Africa, the Bantu languages share common roots, no matter how far apart the speakers may live. These languages retain echoes of the first words spoken by those who migrated from West and Central Africa. The names for crops, tools, and family relations are like markers along the trail of migration, connecting villages in the forests of Central Africa to those in the savannas of the south.

The Cultural ContinuityWhen we examine traditions, we find even more proof of our shared heritage. The Nok people’s artistic expression in terracotta figures still speaks to the cultural importance of ancestors and spiritual guardians. The Bantu-speaking peoples carried with them a similar reverence for the dead, a respect for community elders, and a skill for working the land. These ideas and practices adapted to new environments but kept their original spirit. Even in music and dance, the rhythms and call-and-response patterns echo ancient forms.

The Evidence in Our BloodModern science gives us another way to see the past. Genetic studies reveal patterns that match the routes taken by Bantu-speaking peoples as they spread across the continent. These patterns show that today’s Africans, from Cameroon to South Africa, share ancestral links that reach back to the early farmers and metalworkers of West Africa, and even further to the Nok whose culture thrived more than two thousand years ago.

Why This History MattersWhen Africans see themselves as heirs to a continuous and connected history, it changes how we understand our place in the world. We are not a people defined only by the arrival of outsiders or the borders drawn in recent centuries. We are the continuation of civilizations that shaped the land, built societies, and influenced the course of human history. To know this is to stand with the strength of all those who came before us, carrying their legacy into the future.

Preservation of African Heritage Through Archaeology – Told by DiopI have always believed that a people without knowledge of their past are like a tree without roots. Africa’s heritage is vast, stretching back to the dawn of humanity, yet much of it lies hidden beneath the soil or scattered in the memories of our elders. If we do not protect these treasures—both the objects we can hold and the stories we can tell—we risk losing them forever.

The Work of ArchaeologyArchaeology is more than digging for objects; it is the science of uncovering the lives of those who came before us. A fragment of pottery, a rusted iron blade, or the ruins of an ancient settlement can speak to us about how our ancestors lived, what they valued, and how they shaped the land. Each discovery adds another thread to the tapestry of our history, making it whole again. Without this work, our picture of the past would be incomplete, blurred by time and neglect.

The Power of Oral HistoryBut not all history rests in the ground. Much of it lives in the voices of elders, in the songs, proverbs, and genealogies they pass down. Oral history is a bridge that connects us to the past without the need for written records. It carries the values, beliefs, and wisdom of countless generations. Just as archaeologists preserve artifacts, we must preserve these voices before they fade into silence.

The Role of ScholarshipPreserving our heritage also means studying it with care and integrity. Scholars must work with communities, respecting their knowledge while bringing scientific methods to support and expand it. We must write our own histories, publish our own research, and teach our children about the greatness of the civilizations that came before them. This is not merely academic work—it is an act of cultural survival.

A Legacy for the FutureOur heritage is not only for us; it is a gift we must pass to those who will come after. When future generations can walk through a museum and see the work of the Nok, hear the stories of the Bantu migrations, or read the wisdom of our ancestors in their own languages, they will know they are part of something greater. In protecting the past, we give our descendants the tools to shape their future with pride and purpose.

Archeologists Debate of the Origin of the Nok and Bantu: By Diop and MufweneA Fictional Meeting of Minds and TimesIt was in the shade of a great baobab tree that I, Mufwene, found myself in conversation with Cheikh Anta Diop. The afternoon air was warm, and the hum of insects filled the pauses between our words. We had come together to speak of a matter that has stirred both scholars and storytellers—the origins of the Nok and Bantu cultures. I carried the voices of the elders, shaped by generations of oral history. He carried the weight of years of research, archives, and scientific study.

The Question of the NokI began by speaking of the Nok, whose terracotta figures and mastery of iron have lived on in memory and in the earth beneath our feet. “Their art speaks to us,” I said, “but it does not tell us from where they first came. My elders tell stories of people rising from the very soil they farmed, shaping their lives in harmony with the land. To me, this says they grew from earlier peoples of West Africa, not as strangers, but as children of the same earth.”

Diop nodded but leaned forward with the precision of a scholar. “It is possible they developed from earlier West African roots,” he said, “but we must not dismiss the signs of contact. The styles in their art, the methods of iron smelting—these hint at exchanges beyond their immediate neighbors. Some of these could have come from the north, across the Sahara. Trade routes existed long before our written records. Even without armies or empires, ideas and skills could travel great distances.”

Influence or IndependenceI countered gently, “If they learned from others, then those ideas became something new in their hands. The Nok were not mere imitators. Their terracotta figures carry a style that is uniquely theirs, their iron tools made for their own ways of farming and living. Influence is not the same as origin.”

Diop agreed but reminded me, “The truth may be a blend. Civilizations rarely rise in complete isolation. The challenge for us is to trace the paths—was it the Nok who inspired others, or did they themselves stand on foundations laid by peoples even older, perhaps in lands farther away?”

The Bantu PathwaysWe turned then to the Bantu migrations, a matter close to my heart. “Our words,” I said, “are the map of our journey. Across thousands of miles, we carry the same roots in our speech. This tells us we began together, in lands of West-Central Africa, perhaps near Cameroon. From there, our families spread east to the Great Lakes, south to the savannas. These routes live in our stories, in the names of rivers and mountains.”

Diop’s eyes brightened. “And yet,” he said, “modern science adds more detail. Genetic studies confirm those connections but sometimes tell of movements far older than the oral maps suggest. It may be that what you see as one great migration was many waves over centuries, sometimes advancing, sometimes turning back. Linguistics supports the unity of the Bantu tongue, but DNA reveals smaller exchanges—hunter-gatherer groups joining the Bantu, Bantu settlers absorbing local peoples. It is a more tangled journey than a single road.”

The Tension Between Memory and ScienceI smiled at this. “Memory is a guide, not a chain. We keep the essence, but details may blur. Science sharpens some edges, yet it can also miss the spirit of the story. You speak of waves and genetics, but I think of the songs sung in a new land, the way a farmer plants the first yam in a place where his people have never lived before. Both views are needed, for without one, the other feels incomplete.”

Diop agreed, his voice firm but respectful. “We must let the stories and the science speak to each other. Oral tradition can point us toward questions we would not think to ask, and archaeology or genetics can uncover truths the stories have hidden or reshaped.”

Where the Debate LeadsAs the sun lowered, we found ourselves not in disagreement, but in a shared search for balance. We both believed the Nok and Bantu peoples were part of a larger African heritage—one that was rooted deeply in the continent but open to influence from beyond its borders. The debates over their origins were not signs of uncertainty alone; they were proof that Africa’s history was as complex and dynamic as any in the world.

I told him that in my way, I would keep telling the stories, so the people would remember where they came from. He promised that in his way, he would keep searching for evidence to confirm and enrich those stories. Between us, perhaps, the voices of the past and the tools of the present could weave a fuller picture for those yet to come.

Comentarios