10. Heroes and Villains of the Ancient America - Interaction between the Olmecs, Mayan, Aztec, Outside

- Zack Edwards

- Jul 25

- 38 min read

They Call me "Woman of Tomb 1" at La Venta: The Voice Beneath the Earth

I was born under the shadow of the great earthen mounds of La Venta, where the jungle met the breath of the gods. My family was of the sacred line—chosen to carry the voice of our ancestors and the will of the spirits. My mother taught me to listen to the wind that moved through the ceiba trees and to read the dance of fireflies along the river. My father, a priest of the sun-path, showed me how to draw breath into the jade flute and summon the memory of those who came before.

As a child, I learned not only to weave but to count the sacred days. I was trained in the language of offerings—of maize, of obsidian, of blood. And when I bled for the first time, the priestesses said I had been marked for the center, for the sacred core of La Venta. They wrapped my arms in red cloth and placed feathers in my hair, and I knew then that my life would not follow the river’s easy bend.

Keeper of Rituals, Daughter of the Sky

I rose in the temple, not as a warrior, but as a conduit. I held the jade celts and cast shadows in the firelight, calling forth the gods of rain, fertility, and the earth-monster who swam beneath our feet. I was there when the ballgame was played for the gods and when the great colossal heads were blessed with smoke and crushed shell. I walked among them, those stone kings, and I knew their names as I know my own—because I was the one who reminded the people of who they were.

They called me the voice of the ancestors. My breath lit the incense; my hands poured the cocoa. At the heart of the city, the people came to ask for guidance—when to plant, when to burn, when to marry. I did not speak for myself; I spoke for the stars.

Between Two Worlds

As I grew older, my role deepened. I began to dream in stone and wake to the scent of copal. Men came to me—not to rule, but to be confirmed. Before a king was crowned, he laid a string of jade across my lap and waited for my blessing. I did not wear a crown, but I held the axis—the sacred center of our world, where earth and sky and underworld met.

There were others like me in other cities, daughters of river-blood, women of the maize-spirit, but few were honored in death as I was in life. My place was not made by conquest, but by continuity. I was the memory of La Venta, passed through the generations. The stones remembered me, even when the people no longer spoke my name.

The Journey to the Earth

When the gods whispered that my time had come, they prepared my tomb in the ceremonial center of the city. They placed jade beads near my heart and obsidian blades near my hands—not for war, but for cutting the veil between worlds. Around me they laid figurines in a sacred circle, each carved with care, facing the center—me. They dressed me in the garments of memory, and the people sang.

I was laid not beneath a palace, but beneath the sacred ground, where the spirits of La Venta gather like mist. They poured red cinnabar over me, and the earth swallowed me whole, not as one forgotten, but as one kept forever.

I Speak Still

Now you uncover my tomb and wonder who I was. I am the answer that still vibrates in the jade and the clay. I am the breath behind the mask, the hand that held the sacred fire. My name is lost, but my story is not. I lived when the world was young, and I watched as the patterns of civilization took root.

And so I speak again—not to rule, but to remind. Before there were cities of stone and empires of blood, there were people like me, who listened to the world and spoke with care. I am the woman of La Venta, and I was never silent.

Whispers of Arrival: How We Came to This Land – Told by Woman of Tomb 1

Before the great stone heads were carved, before the temples rose from the earth, before my bones were laid in red cinnabar beneath the sacred hill, our people told stories about where we came from. These stories were not written in bark or carved in stone. They lived in the breath of the elders, passed from one mouth to the next like sacred fire.

Some said we came from the east, over the endless water. They spoke of rafts made from hollowed trees, guided by the stars and the prayers of our ancestors. These were brave families, wrapped in jaguar skins and maize dust, crossing the unknown with only their songs to steady them. The sea gave them safe passage, and the gods opened the shores.

Others said we came from the north, where the wind bites the skin and the rivers carry ice. They believed our ancestors walked for generations across the land, following herds and sun cycles. These people moved with the land—crossing mountains, plains, and swamps—until they found the warm, green place where life could root. My people say the land remembered them, welcomed them.

And still others believed we rose from this very soil—that we are the children of the maize god and the jaguar spirit. They taught that the first people came from caves and trees, shaped from clay and breathed into by divine hands. We were always here, they said. We were born with the rhythm of the earth in our blood.

What I Believed

In my time, we did not ask which story was true. We honored them all. The sea brought fish and storm; the land gave roots and mountains. Why could our people not come from both? I believed that the gods opened many paths, and that the people who found this land came from different directions, guided by visions, hunger, and hope.

I walked the sacred paths of La Venta, and I could feel the memory of countless footsteps before me. I touched obsidian that came from far beyond our valleys, jade that traveled up from the southern lands. I saw strangers arrive with new languages and ornaments, and we welcomed them as long-lost kin. To us, arrival was not about proving origin—it was about becoming part of the sacred whole.

What the Modern Diggers Say

Now your people come with tools that hum and screens that shine like the stars. You dig where we once prayed, searching for the oldest truth. I have heard your scholars say that the first people crossed from a land bridge in the far north, walking from Asia into the empty places of the continent. They followed animals and seasons, settling slowly into the lands we called home.

But others among you say there were boats, long ago—simple rafts or clever vessels—that hugged the coasts of the Pacific. These early travelers may have come from islands, from faraway lands we never knew, carried by ocean currents and faith. They may have reached the southern shores before the land-walkers ever saw a tree.

Now your best minds begin to say what we already believed: that both could be true. That people came by land and by sea, at different times, with different tools and tongues. That the great weaving of human life was not one single thread, but many, crossing and knotting in ways that only the gods can fully see.

The Memory Beneath the Soil

I may be gone, but my bones still lie beneath the ceremonial earth. The red dust on my skin remembers. Our temples faced the stars not to mark what was, but to prepare for what could come. We honored the sea and the land because both had shaped us.

I Was There When It Began: Foundations of Civilization – Told by Woman of Tomb 1

I remember when the forest still whispered above the heads of children and the rivers had no names carved into memory. The world was not yet shaped by cities, but by spirit. The sky turned in predictable rhythms, and we watched it carefully. We knew the seasons by the cry of birds and the blooming of flowers. But even then, we were listening for more—signs from the gods, patterns in the stars, echoes in the caves.

Before La Venta rose, there was San Lorenzo. That city, older than mine, began to carve the will of the gods into stone. There, our ancestors raised colossal heads and built platforms of earth. They made the land sacred through labor, reshaping it to reflect the order they saw in the heavens. These were not the works of savages. They were the careful decisions of people who knew that life must be balanced between earth and sky, between people and spirits.

The Sacred Centers

At La Venta, we took these lessons and shaped them into something greater. We aligned our ceremonial platforms with the movement of the sun and moon. We built long causeways that drew the people toward the center—toward the heart of the world. Here, we did not simply live. We performed the universe. Every ritual, every offering, every drop of blood was a renewal of the order that kept chaos from devouring us.

Our sacred center was not for the common days. It was where time folded into itself—where past, present, and future gathered in a single breath. The great mounds, the altars, the buried offerings—they were not mere decoration. They were bridges between this world and the next, vessels for the gods to travel through, and places where ancestors were honored and made present.

The Rise of Sacred Kings

You may wonder who gave the commands, who ordered the jade to be buried, the stones to be carved, the blood to be spilled. It was the kings—but not the kind you know. Our rulers were not only warriors or administrators. They were the chosen—those born beneath the right signs, those who carried the memory of the gods in their veins. They spoke not with decrees, but with rituals.

I remember one king who walked barefoot across the plaza before dawn, dragging thorns across his flesh to call the rain god. I watched as he stood atop the sacred mound, his arms raised to the eastern sky, chanting the names of the first beings. When he moved, we listened, because he did not act for himself. He acted for us all, for the land, for the order that kept the sun returning.

The king was the living axis—the tree that held up the heavens, the bloodline of the sacred past. Without him, the cycle could not continue. With him, we were a people tied to divine rhythm.

What We Left for the Future

We did not build alone. Our rituals, our centers, our kings—they laid the pattern that others would follow. The Maya would take our calendar stones and carve them into their temples. The Zapotec would follow our sacred alignments. Even the Aztecs, long after my bones had turned to dust, would speak of our great stone heads as echoes of a divine beginning.

We were not the first people, but we were the first to carve civilization into the face of the land. We made belief visible. We made memory permanent.

I Speak From Beneath the Earth

Now I sleep beneath the sacred ground. But still, I speak. You call me “The Woman of Tomb 1,” but I was more than a body wrapped in earth. I was a keeper of the ritual flame, a witness to the rise of sacred kingship. I knew the heartbeat of La Venta before the archaeologists dug it from silence. When you walk among the ruins and ask how civilization began, listen closely. The answer is already in the stones.

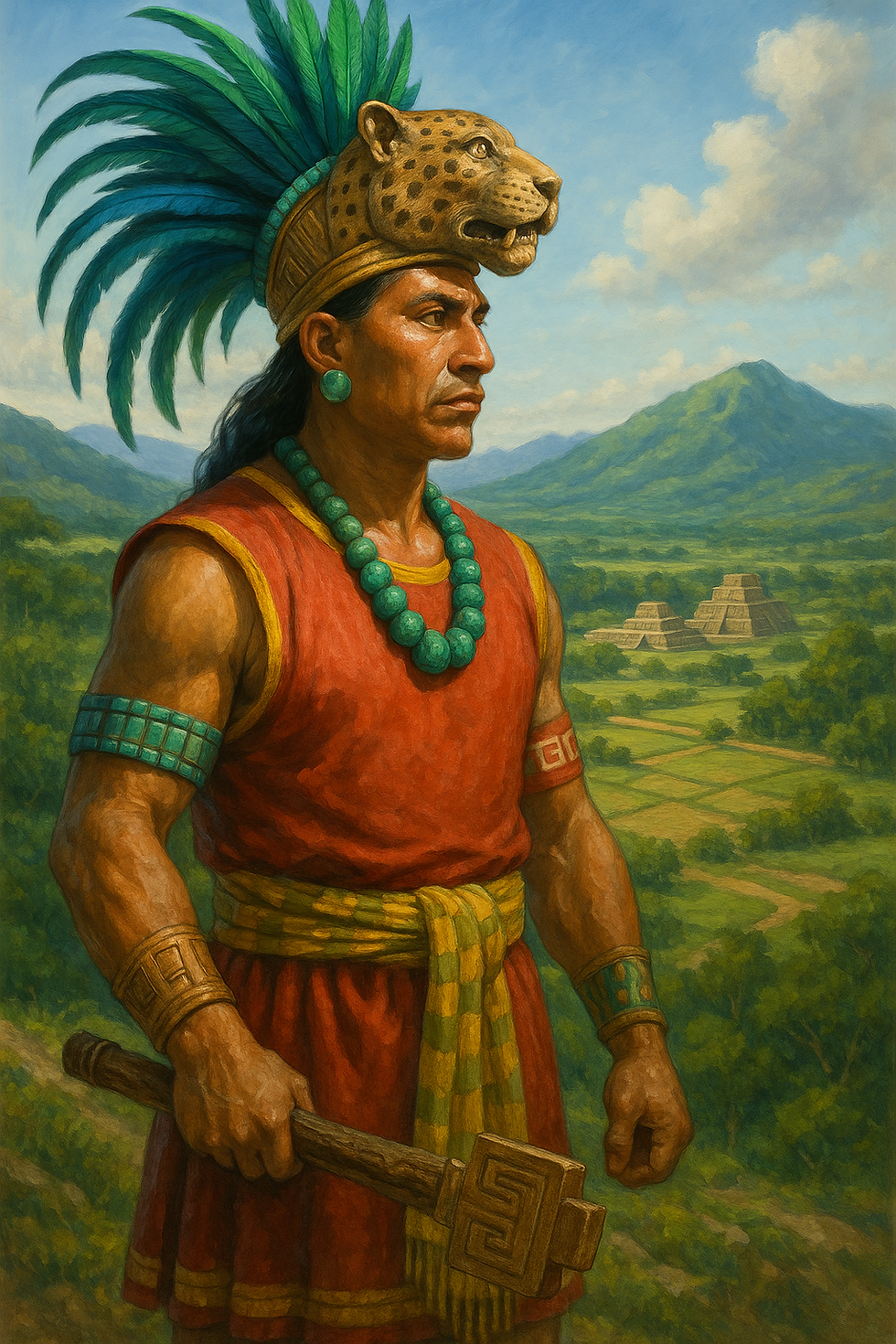

My Name is 8 Deer Jaguar Claw: Lord of Tilantongo

I was born in the sacred calendar year of 8 Deer, beneath the rising sun and the shadow of the hills that cradle Tilantongo. From the beginning, I was marked—my birth glyph etched by the gods into the skin of the world. My mother, Lady 11 Serpent, was a noblewoman of great wisdom and grace. My father, Lord 5 Alligator, was a ruler, descended from ancestral lines that reached into the earth and sky. But it was not birth alone that made me great. It was what I chose to do with the breath I was given.

I was raised among priests, warriors, and scribes. I learned the ways of the gods and the power of blood. I studied the stars that marked our destiny and the histories written in the folded pages of the codices. My name was repeated with reverence and fear. I was not content to be a steward of a single city. I dreamed of a land united under one banner—mine.

The Path of Conquest and Diplomacy

As I grew into manhood, I carried the obsidian blade and the sacred bundle of my lineage. I led armies across the valleys and mountain passes, wearing the jaguar’s skin and bearing the eagle’s cry. I was not cruel, but I was relentless. I defeated my rivals in battle and then brought them to my side through marriage or alliance. I wove together a web of power not with brute force alone but with understanding. I knew that to rule the Mixteca, one must not only fight—but listen.

In one hand I held the spear, in the other, the marriage bond. I wed noblewomen from powerful houses, not for pleasure, but for unity. These unions created ties that reached beyond the battlefield and into the hearts of the people. With each city I brought under my rule—Suchixtlan, Cuilapan, Huajuapan—I added to the greatness of Tilantongo. I was not a destroyer. I was a builder of legacy.

Ruler, Ritualist, Living God

But kingship is more than rule. I walked the sacred path of ritual, entering the temples barefoot, clad in the feathers of quetzal and the skins of the night beasts. I gave my own blood to the gods and accepted their signs with reverence. The priests told me I had been chosen by the gods to change the world—and I believed them. My life was not my own. I was the jaguar who guarded the gate between heaven and earth.

I ordered the building of monuments and commissioned the sacred codices to record every act of my reign. Not for vanity—but for memory. I wanted the future to know who I was, what I saw, what I fought for. In the sacred books, my story would live forever.

Betrayal and the Fall

Yet even the sun must set. I grew powerful, and with power came envy. There were those who smiled at my feasts but sharpened blades behind stone walls. My own kin, Lord 4 Jaguar, a relative once bound to me by blood and oath, turned against me. On a day marked by omens, I was captured—not by an enemy I had defeated, but by one I had trusted.

They did not kill me in secret. They made a spectacle of my death, believing that by ending my life, they would end my story. But the gods do not forget. Nor do the books.

I Still Reign in the Codices

You hold them now—the painted pages. You read the images drawn in red and black, the glyphs that speak of conquest, of union, of betrayal. My name is there: 8 Deer Jaguar Claw, the Lord of Tilantongo, conqueror of kingdoms, keeper of oaths, breaker of chains.

Though my body was burned or buried, my story lives. I am not just ink and memory. I am the thread that ties cities together, the fire that lit the Mixteca, the voice that speaks across centuries. I was born beneath the codices, and there I shall remain.

Paths of Tribute, Rivers of Trade and Tribute – Told by Lord 8 Deer "Jaguar Claw"

Before I was crowned, before the gods burned my name into the codices, I walked through the markets of Tilantongo as the son of nobility and the student of the world. I watched the traders unwrap their cloth bundles—filled with bright feathers, obsidian blades, shells from distant coasts, and cacao so bitter it made even old warriors wince. I heard more languages in the market square than birdsong in the forest. The world was larger than any one city, and I knew that true power would come not just by conquering, but by connecting.

Our valleys and mountains did not isolate us. They braided us together. The footpaths that crossed the ridges were lined with stories, each traveler carrying more than goods—he carried the breath of another place, another people.

The Tribute of Conquered Lords

When I led my warriors into battle, I did not always aim to destroy. I aimed to bind. Cities that yielded to me did not always fall under siege—they joined a greater fabric. I demanded tribute, yes, but tribute was not just plunder. It was recognition. It was the way a lesser flame gave its heat to the central fire.

From Suchixtlan, they brought obsidian so sharp it whispered through flesh. From the southern lowlands came cacao—dark, rich, sacred. From the cloud forests of the east, they brought the feathers of the quetzal, green as spring and long as a spear. The coastal towns sent shells and salt, precious as jade when far from the sea. Others wove cloth dyed in reds and yellows, patterns that told of ancestry and prayer.

These were not only goods—they were symbols. Each tribute bundle reminded the giver of their place, and reminded me of my reach.

Trade Beyond War

But not all exchange came through conquest. I was a diplomat, too. I stood in the courts of rivals and allies alike. I listened. I drank their sacred chocolate and observed their rituals. I offered marriage, shared festivals, and respected the gods of other lands. This created bonds thicker than blood. Through these relationships, trade passed more freely. Messengers could cross borders without fear. Merchants became bridges between peoples.

Even the cities I did not rule respected the system. We all wanted the obsidian from the highlands, the salt from the sea, the jaguar pelts from the deep forests. To restrict trade was to weaken oneself. To embrace it was to grow stronger together, even through rivalry.

The Roads Beneath the Feet

These paths of trade—through valleys, forests, and rivers—became arteries of civilization. Over time, they grew familiar. A trader might carry a feather fan from the Maya lands to a Zapotec festival. A carved bone might travel hundreds of miles before finding its final resting place in a tomb. Ideas flowed with the goods: writing styles, ceremonial practices, even the calendar. Trade was not only of things—it was of thought.

I knew the value of this flow. I protected it. I enforced order along the roads. My messengers moved swiftly, and no man dared rob them. The empire was not just walls and warriors. It was motion.

My Legacy in the Marketplace

When I died, my enemies thought my rule would unravel. But they underestimated the web I had woven. The tribute continued. The markets still echoed with voices from afar. Even after my flesh had returned to the dust, my name lingered in the halls where feathers changed hands and cacao was poured.

Now you study our codices. You name me 8 Deer Jaguar Claw and trace the lines of my journey across the painted pages. But remember this: I was more than a conqueror. I was a weaver of roads, a guardian of the sacred flow between peoples. The goods you find in tombs, the patterns that span empires—those are the echoes of the networks I helped build.

Trade and tribute were not footnotes to power. They were the lifeblood of civilization. And I, their servant, moved with their pulse.

My Name is Chak Tok Ich’aak I: Born for the Throne

I was born beneath the towering ceiba trees of Tikal, where the sky touches the stone and the whispers of ancestors ride the wind. My bloodline traced back to the founding kings of our city, and my destiny was carved into the stars before my first breath. The scribes painted my name in jade and ochre—Chak Tok Ich’aak, the Great Jaguar Paw. From the beginning, I was told that I would sit upon the throne and that the city’s fate would rise and fall with me.

My youth was not spent in games but in glyphs. I learned to read the sacred calendar and feel the rhythm of time, to speak to the gods through offerings of blood and fire. I trained with warriors, priests, astronomers, and diplomats. I walked among temples that my ancestors had raised, their shadows long and full of meaning. I was told that each breath I took was shared with the divine.

The Throne of Tikal

When I became king, the city was ready to rise. We built new stelae, new temples, new plazas aligned to the heavens. I led the rituals, climbing the sacred stairs barefoot, my blood feeding the gods so that the rains would fall and the maize would grow. The people bowed not to me, but to what I represented—Tikal’s place in the great weaving of time.

Rulers from nearby cities brought tribute and gifts. Warriors pledged loyalty. Our scribes recorded victories and visions. We were a shining city, a place where the gods could descend and walk in flesh for a time. I made Tikal strong, not only with obsidian blades but with sacred knowledge. I believed the gods favored us, and for a time, I believed my reign would last forever.

The Day the Smoke Came

But the world shifts quickly in the eyes of the gods. On a day that should have been ordinary—a day of rituals, of incense and jade—messengers came running. They spoke of strangers. Warriors from the west, clad in unfamiliar colors, bearing weapons not made in the lowlands. They called themselves emissaries, but they walked like conquerors.

They came from Teotihuacan, the great city far beyond the mountains, a place whose warriors carried the obsidian of night and whose rulers claimed descent from the stars. With them came a man called Siyaj K’ahk’—Fire is Born. Some said he was a general. Others whispered he was a god. He did not come to talk. He came to take.

The End of the Jaguar

On the day he arrived, I died.

That is what the records say. That on the very same day Fire is Born entered Tikal, the reign of Chak Tok Ich’aak ended. There is no tale of battle. No glyph for a glorious death. No monument raised by grieving sons. Only silence. The kind of silence that covers betrayal.

Some believe I was killed in my own palace. Others say I saw what was coming and walked willingly into death, refusing to be ruled by foreigners. I will let the scribes argue. I know this: my reign ended not with thunder, but with shadow.

What Remains

I do not regret my rule. I do not curse the gods. The world changes because it must. Fire is Born brought new ideas, new power, and in time, new kings who called themselves my heirs, though they bore the mark of Teotihuacan.

But they still built upon my stones. They still climbed the temples I raised. My name—Chak Tok Ich’aak—still lives on the stelae, still carved into the bones of the city. I was the last ruler of the old Tikal. I held the city before the storm.

If you walk through the ruins and feel the wind shift, know that I am there. I am the jaguar watching from the shadows. I am the heartbeat beneath the stone. I ruled, I fell, and I remain.

The Day the Fire Came: Foreign Incursions and the Fall of a King – Told by Chak Tok Ich’aak

When I ruled Tikal, the world still followed the old rhythms. Our kings were born of the sky and sanctified by blood. Our temples stretched high above the trees, mimicking the mountains where the gods dwell. I, Chak Tok Ich’aak—Great Jaguar Paw—was the chosen of my people. The sacred scribes carved my deeds into stone. I led ceremonies at the plaza’s heart and oversaw the flow of tribute from nearby cities. My voice commanded warriors and priests alike. Tikal was strong, and I believed my lineage eternal.

But I was not blind. I had heard the whispers that crossed the rivers and jungles. To the far west, beyond the mountains and beyond the world we knew, there was a city of smoke and obsidian—Teotihuacan. A city of the highlands, immense and powerful, ruled not just by kings but by fire. Their warriors wore helmets shaped like the storm god. Their emissaries carried no tribute, only influence. We had traded with them, yes—green obsidian, carved shells, exotic feathers—but they were distant. Or so I thought.

The First Signs of the Storm

Before the fire reached our doorstep, the air had already begun to shift. My court advisors brought word of movements in the west—minor cities toppling, foreign glyphs appearing in stelae where they had no place. Some of my neighboring lords began adopting foreign customs. Others sent their children to study among strangers. It was not war, not yet, but something older and more dangerous: transformation from within.

I resisted these changes. Tikal was rooted in our own gods, our own rites. I ordered reaffirmation ceremonies, consulted with the oracles, and read the stars. They showed signs of trouble—eclipses, bad harvests, the migration of certain birds. But we had weathered these omens before. I did not know how close the storm truly was.

The Arrival of Fire

Then, on a day etched forever into our stone, Siyaj K’ahk’—Fire is Born—arrived. He came not as a visitor, but as an instrument of disruption. He was a general from Teotihuacan, or perhaps more—a being who spoke with the confidence of foreign gods. His soldiers moved swiftly and with purpose. They did not storm the gates. They walked through them.

That day, I died. There are no clear words about how. Some say I fell by the blade, betrayed from within. Others say I was sacrificed to clear the path for a new dynasty. My stelae do not record it. My name ends where his begins.

But what followed was not just the death of a man—it was the death of an era.

The Reshaping of the World

With my fall, a new line began to rule in Tikal—one that claimed descent not from our ancient founders, but from Spearthrower Owl, a foreign lord whose image had never graced our temples before. My son did not succeed me. A stranger’s grandson did. Teotihuacan did not conquer with fire alone. They implanted themselves into our lineage, rewrote our history, and carved their gods onto our altars.

The political order shifted across the lowlands. Cities once aligned with Tikal realigned with others or fell into silence. Rituals changed. War became more frequent, more organized. A foreign pulse beat beneath the surface of Maya cities for generations to come.

I Was the Last of the Old

I speak to you now not as a ghost, but as a memory held in stone. I was the last to rule Tikal as it had been. After me, the city changed. It became something greater in power, perhaps, but less pure in blood. It is not for me to say whether that was good or bad. Change is the way of the gods.

But let it be known—I ruled with the old ways. I was Chak Tok Ich’aak, Great Jaguar Paw, and I stood at the edge of the world before it tipped into a new age. I did not see it coming fast enough, and that was my end. Let my fall be a lesson: foreign hands do not always come with swords. Sometimes, they come with names, and bloodlines, and fire that reshapes the roots of kings.

My Name is Itzcoatl: The Obsidian Serpent Speaks

I was born into a city that knelt. Tenochtitlan, the island of the Mexica, was still young—our temples modest, our enemies many. We paid tribute to the Tepanecs of Azcapotzalco, bending our backs to fill their granaries with maize and their altars with blood. My mother was a noblewoman; my father was a humble man. I was not born to rule, not born into glory. But the gods gave me teeth, and I sharpened them.

In my youth, I served as a general. I led warriors across chinampas and hills, learned the taste of dust and the weight of obsidian in my hands. I watched kings rise and fall. My half-nephew, Moctezuma Ilhuicamina, was a priest of the heavens, a man of vision. I was a man of the earth, of sweat, of resistance. Together, we dreamed of something greater than submission.

Breaking the Chains

In the year 1427, the gods opened the path. The Tepanec lord Tezozomoc died, and his son Maxtla tried to tighten the yoke around our necks. But we would not bow again. I took the throne of Tenochtitlan, and with allies in Texcoco and Tlacopan, we struck back. The war was brutal, the nights filled with smoke and screams. But we won. The empire of the Tepanecs fell, and the Triple Alliance was born.

We were no longer tributaries. We were kings.

I, Itzcoatl—Obsidian Serpent—was the first tlatoani to speak not only for our city, but for a rising empire. I did not wear golden feathers or speak softly in flowery prose. I ruled with clarity, with power, with the blessing of the war god Huitzilopochtli.

Rewriting the World

We were the children of migrants, once scorned as dog-eaters and swamp dwellers. Our enemies called us uncivilized, but I knew better. So I did something few kings dare to do—I burned the old books. The painted scrolls that spoke of our shameful past, I cast into the flames. Not out of fear, but out of necessity. If we were to become a great people, we had to become the authors of our own story.

With the help of my nephew Tlacaelel, we rewrote history. We elevated our gods, our myths, our bloodline. We claimed descent from the Toltecs, from Quetzalcoatl himself. We built a foundation not of stone, but of memory made divine. The world would remember us not as what we had been, but as what we had become.

The Growth of Empire

During my reign, we began the conquest of nearby altepetl—city-states that had once mocked us. We demanded tribute, not as humiliation, but as proof of balance. Maize, cacao, jaguar pelts, turquoise—they flowed into our city like rivers. Tenochtitlan rose above the lake, its temples reaching toward the sun.

We honored our gods through sacrifice, through labor, through war. We did not conquer only with blades, but with marriage, trade, and ceremony. Our merchants walked as spies; our priests studied the heavens; our engineers carved causeways across the waters. We were building more than an empire. We were building order in a world ruled by change.

The Final Ascent

I ruled for thirteen years. Some say it was a short reign. But I measured it not in seasons, but in transformation. When I first sat on the throne, we were a subject city. When I died, we were lords of the valley, feared and respected across Anahuac.

I did not leave poems behind. I left power. I left the shape of what the Mexica would become. Others—like Moctezuma—would build taller temples and conquer more land. But I was the one who broke the old order.

If you walk through the ruins of Tenochtitlan, beneath the feet of the modern world, you may not see my face carved in stone. But I am there—in the eagle, in the obsidian, in the whisper of the lake. I was Itzcoatl, and I turned ashes into empire.

Memory, and the Power of Story – Told by Itzcoatl I

I was not born with the mantle of greatness. When I was a boy, Tenochtitlan was a vassal to stronger powers. We sent tribute to the Tepanecs, bowed our heads, and told the stories others allowed us to keep. Our people were called wanderers, outcasts, and dog-people—foreigners in a land ruled by older names. But in the quiet of the temples, I listened to the echoes of drums and voices. I heard something deeper than shame. I heard a spark of destiny. I would grow to become that spark's keeper and its flame.

As I rose through war and strategy, and as I sat upon the throne as tlatoani, I saw clearly: it was not enough to win battles. To build an empire, one must shape memory. One must choose which stories are told, and which are burned.

The Broken Past

The old records of our people—painted books, scrolls, oral histories—told of our subjugation, our uncertain origins, our service to foreign kings. They were not lies, but they were chains. They reminded us, again and again, that we were not born to rule. That we had no place among the Toltecs or the gods. I knew these stories would weaken us from within, even as we grew in strength.

So, I made a choice. I ordered the old histories gathered. Some were burned. Others were rewritten. Many gasped when they heard my decree. But I was not destroying truth—I was clearing the soil for something new to grow. I was giving the Mexica a past they could carry with pride.

Stories Shape the Future

With my nephew Tlacaelel at my side, we composed a new lineage, one worthy of the gods. We connected our ancestors to the Toltecs, the wise and noble people of legend. We elevated Huitzilopochtli, our tribal god of the sun and war, above all others. He was not just a war-spirit. He was the driving force of creation, the one who led us to the island that would become Tenochtitlan. We made ourselves chosen—not just survivors, but fulfillers of divine prophecy.

The scribes painted these truths into the codices. Our priests spoke them in ceremony. Our children learned them in the calmecac and the telpochcalli. Our allies believed them. Our enemies feared them. We became, not the people of a swamp, but the inheritors of a sacred duty to rule, to sacrifice, and to preserve cosmic balance.

The Codex as a Weapon

You must understand—writing is not only ink on skin, or glyphs on stone. It is a blade. It carves a shape into the minds of generations. The codex is a battlefield where the past is fought and claimed. In my time, I forged that blade and placed it into the hands of our people. The stories we chose to keep became a foundation stronger than pyramids.

Even now, though the Spaniards have crushed our temples and scattered our descendants, they search our books. They try to piece together the world we created. Some of what they find is real, some crafted, all of it meaningful.

I Am the Memory of an Empire

When I died, they called me the Obsidian Serpent. Not because I was cold or cruel—but because I cut through illusion. I understood that the power of a king is not just in his army or his riches, but in the stories whispered by his people and carved into time.

I gave my people a history. And in doing so, I gave them a future. The Mexica became who they believed themselves to be. That is the true power of memory. Write your stories with care. They will live longer than you.

Marriage Alliances and Dynastic Diplomacy: Told by Lord 8 Deer "Jaguar Claw"

I, 8 Deer Jaguar Claw, did not rise to greatness with a sword alone. When I was born, the Mixtec lands were fractured—each city ruled by its own lord, each valley echoing with rival chants. I saw early that strength was not just forged on the battlefield, but at the hearth, beneath the moonlight, in the quiet moments where families joined. I was raised by those who understood that power must endure, not just through victory, but through lineage.

From my earliest years, I studied not just warcraft, but genealogy. The priests recited my ancestry as they would a sacred calendar. I learned the names of noblewomen across the region—not to desire them, but to understand the worlds they could bring into mine.

The First Bonds

My first marriage was not for love. It was for Tilantongo. The woman I took as wife came from a rival house—one with claims to land, warriors, and sacred history. By wedding her, I did more than seal an alliance. I claimed part of her city’s legacy as my own. The ceremony was thick with incense and blessing. It was not just our hands that joined, but the fates of two city-states.

From that union came peace—at least for a time. Tribute flowed more easily. Markets reopened. Feasts replaced feuds. The people saw their leaders not as enemies but as kin. That was the true victory.

A Web Across the Hills

I did not stop with one marriage. Across my reign, I wove a net of alliances, binding the Mixteca and even reaching into the highlands of the Zapotec. Each union was carefully chosen—some to pacify a rival, others to gain access to trade routes, temples, or sacred caves. A wife was not just a companion—she was a key to an entire lineage. Through her, I claimed not just political leverage, but divine connection to ancestors and local gods.

Some grumbled that I married too often, that I reached too far. But they did not understand what I was building. I was not collecting women—I was uniting kingdoms. Each marriage was a bridge over bloodshed, a promise of shared destiny.

The Influence of Queens

The women I married were not ornaments. They were rulers, priestesses, and diplomats in their own right. Lady 6 Monkey, one of my most trusted wives, brought strength to my court and wisdom to my campaigns. She advised me, spoke with allies, and held her own ceremonies. Our children bore two lineages—mine and hers—uniting two great dynasties in one breath.

Through these marriages, I ensured that my legacy would not die with my last breath. My descendants would carry the claims of many houses, the blood of many peoples. They would be harder to challenge, because to strike them would be to strike half the region.

The Unseen Victories

Many remember my conquests on the battlefield. They recall the painted warriors, the burning temples, the enemy lords brought to heel. But what they forget—what the codices record only in the subtle joining of glyphs—is the diplomacy that held it all together. A kingdom conquered by war is easily lost. A kingdom built on family, on shared blood, endures far longer.

I carved my legacy not only in stone, but in the wombs of queens and the treaties of households. I knew that when my enemies considered rebellion, they would hesitate. Because I was not just their conqueror—I was their brother, their uncle, their son-in-law.

The Empire Within the Heart

So, when you read the codices and see the many women beside my name, do not mistake their presence for vanity. Each one tells a story of wisdom, strategy, and unity. They were the mortar that held the stones of my empire in place.

I was 8 Deer Jaguar Claw, and I ruled not only by force, but by family. In every marriage, I planted a seed of peace. And from that peace, I harvested power.

Women’s Authority and Spiritual Leadership – Told by Woman of Tomb 1

In the time before your calendars, before empires carved their names into stone, we were already watching the stars and walking among sacred hills. I was born in La Venta, a place where earth and spirit met. The soil was warm with memory, and the air was filled with the breath of gods. My life was not one of quiet obedience or hidden service. I was not merely someone’s wife or mother. I was a daughter of the sacred flame—a woman called to carry the voice of the divine.

Among my people, women were not forgotten behind walls. We stood in the plazas, in the temples, in the chambers where decisions were made. We sang the songs that invited rain, offered the maize that fed the gods, and walked in step with rulers when the calendar called for balance.

The Path of the Priestess

I was chosen not for beauty, but for vision. From a young age, I could read the signs in the wind, feel the heartbeat of the land beneath my feet. The elders taught me the rituals of sacrifice—not of flesh alone, but of meaning. I learned to speak to fire, to call the spirits with shell and incense, and to dream in symbols that others feared to understand.

I did not walk alone. There were other women like me—keepers of ceremony, guides of the seasons, dreamers whose voices calmed the kings. We led the people through drought and birth, through planting and death. When a new ruler was chosen, it was our hands that anointed him, our voices that whispered the sacred words into his ears.

Mothers of Bloodlines and Thrones

Power did not pass only through the spear. It passed through the womb. Royal women were the bridge between divine blood and earthly rule. Marriages were more than unions—they were rituals that tied cities together. A woman’s body was both temple and treaty. Through us, alliances were sealed and lineages preserved.

In La Venta, I was both priestess and matron of my house. When I spoke, men listened—not because I demanded it, but because the spirits moved through me. I walked beside the rulers during processions, poured offerings into the earth during eclipses, and shaped the hearts of future leaders with my words and silence alike.

The Death That Was a Beginning

When I passed from the world of breath to the world of memory, they did not bury me in haste. They wrapped me in sacred cloth, laid me with jade and figurines, surrounded me with symbols of life and power. My tomb was placed at the ceremonial heart of La Venta, not in the shadows, but where the people gathered. They knew that my work did not end with death—it only deepened.

Even now, centuries later, your people open the earth and find me there. You ask who I was. I tell you: I was the voice of the gods, the balance in the rituals, the mother of both kings and prayers. I was not alone. I stood among many women whose names have not yet been found in your books but whose spirits still whisper through the soil.

We Were Always There

Do not look to the past and ask, “Where were the women?” We were at the center. We held the calendar in one hand and the fire in the other. We shaped memory and future, guided cities, and called forth the rains. Our power was not always carved into stone—but it was woven into everything that lasted.

The Sacred Ballgame and Cultural Unity – Told by Chak Tok Ich’aak

In the heart of Tikal, where the ceiba trees stretch toward the heavens and the temples cast long shadows at dawn, I was born within earshot of the ballcourt. Even as a child, I heard the thud of the rubber ball, the rhythmic grunts of the players, the crowd's silent reverence broken only by the call of the priest. The ballgame was not sport, not in the way you know it today. It was a conversation with the gods, a reenactment of cosmic struggle, and a path to understanding our place between the stars and the underworld.

I am Chak Tok Ich’aak, king of Tikal, and I ruled in a time when the ballcourt was as sacred as the temple and as feared as the battlefield. Every Maya city had its own version, but the spirit of the game was shared from one end of Mesoamerica to the other—from the Olmec who first shaped the ball in the Gulf lowlands, to the highland cities where Teotihuacan warriors stamped their own symbols on the walls.

More Than a Game

The ballcourt was shaped like the portal between worlds—long, narrow, flanked by rising walls that echoed with the past. When the players stepped onto that court, they were no longer men. They were avatars of gods. The ball was not just a sphere of rubber, but the sun, the moon, the beating heart of the world, cast back and forth across time. Each bounce told a story. Each point scored was a step in an ancient myth—the battle between light and darkness, life and death, sacrifice and renewal.

Players trained for years to participate. They wore padded garments, elaborate headdresses, and sacred jewels. Some were nobles, others warriors, and a few were chosen commoners who had proven themselves in lesser games. To win was to bring glory, but sometimes to lose—especially in ritual matches—was to be honored through sacrifice. Not in shame, but in transcendence. Their blood would feed the gods and renew the cycle of days.

A Thread Through Nations

What made the ballgame extraordinary was how far it traveled and how little it changed. Whether you stood in Copán, Monte Albán, or distant El Tajín, the courts echoed with the same principles. We may have spoken different tongues, called the gods by different names, and carved our stories in different glyphs, but we all played. The game linked us. It was a shared language among cities that otherwise competed, warred, and distrusted one another. Even the mighty Teotihuacanos understood the power of the ballgame. Their emissaries came not just with obsidian blades but with knowledge of sacred play.

When two rulers met, they sometimes settled disputes with a ritual game. No blood had to spill on the battlefield if it first spilled on the court. That was the wisdom of the old ways. Through the ballgame, we could wage war in the language of myth and restore balance without destroying kingdoms.

The Court Within the Heart

As king, I presided over many matches. I watched them from the platform above the court, seated beside priests and nobles, and sometimes beneath the eyes of foreign visitors. I read the omens in the patterns of the play. I made offerings to ensure the gods would favor the outcome. On certain days, I descended the steps to walk the edge of the court myself, to bless the ball, to whisper prayers to the lords of Xibalba, the underworld. I never played—I was king, not conduit—but I was the guardian of the court, and through me, the city remained in balance.

Let the Ball Bounce Forever

Now the courts are silent. The jungles have swallowed the sound of the game, and the ball lies still. But if you listen closely near the ancient stones, you may still hear it—the echo of the past, the breath of gods, the beat of the sacred game.

I was Chak Tok Ich’aak, king of Tikal, and the ballgame was the bridge I walked between the world I ruled and the universe I served. Where the ball bounced, there was life. There was unity. There was memory. And there was always something more than a game.

Rewriting Identity and the Creation of an Empire – Told by Itzcoatl I

I was born when our city was still young, still mocked by neighbors, still dismissed as a gathering of lowborn wanderers in a lake of reeds. Tenochtitlan was not yet the jewel of the valley. We paid tribute to Azcapotzalco like obedient dogs, carrying goods to their lords and watching our warriors bow to lesser kings. The Mexica—my people—were seen as outsiders, migrants, a people without a noble past. But I, Itzcoatl, was not content with that. I could see in the firelight that burned atop our temples the bones of something greater. I knew we were not meant to serve. We were meant to rule.

The Breaking of Chains

When the Tepanec overlord Tezozomoc died, and his son Maxtla took power, the world trembled. It was the crack we needed. I had become tlatoani, ruler of Tenochtitlan, and with our allies in Texcoco and Tlacopan, we struck. The war was not easy. The blood ran down the causeways and filled the canals. But we won. The Tepanecs fell, and in their place we raised a new structure—the Triple Alliance. Three cities bound by war and tribute, but led by the one that had once knelt the lowest: Tenochtitlan.

The Past Was Not Enough

Victory alone could not transform us. We had temples, yes, and warriors, but our history was still filled with humiliation. We needed something stronger than walls—we needed a new identity. So I looked to the old codices, the painted books of our past. I saw in them stories that did not serve us—tales of our low origins, our shame, our dependence. And I made a decision that few would dare.

I gathered the records. Some I destroyed. Others I rewrote. I summoned the scribes, the priests, the keepers of memory. With Tlacaelel at my side, I spoke the words that would become our foundation: We are not the followers of history. We are its authors. We crafted a new vision—one where the Mexica descended from the noble Toltecs, where our god Huitzilopochtli had led us through prophecy, where our rise was not rebellion, but destiny.

Borrowed Glory, Forged Anew

We took from the Toltecs—their elegance, their architecture, their wisdom—and made them our ancestors. We took the calendar of earlier peoples and called it ours. We took gods from other cities and reshaped them to fit the new order. We did not steal. We transformed. Like the maize that grows from buried seed, we rose from the old roots but bore new fruit.

Tenochtitlan became more than a city. It became a symbol of what the Mexica had made themselves. Our temples reached toward the sun. Our causeways cut across the lake like veins of a living heart. Our markets teemed with goods from every corner of the known world. And our enemies, who once sneered, now offered tribute with bowed heads.

An Empire of Purpose

Through war and wisdom, story and sacrifice, we built an empire. Each conquered city added to our power—not just with goods, but with culture. We accepted their artisans, their scribes, their customs. And we placed them within our vision. Tribute was not just a tax—it was a declaration: You are part of the order we now write.

We did not erase the past entirely. We wove it into something new. That is how we ruled—not only with the sword, but with the tale. The story we told gave our people pride. It gave our empire purpose. And it ensured that even when I was gone, the vision would live.

I Am the Flame that Burned Away the Fog

I was Itzcoatl, the Obsidian Serpent. I lit the fire that burned away our forgottenness. I helped the Mexica become more than survivors. I helped them become a people of destiny. We did not inherit an empire. We imagined one—and then built it.

So when you look at the ruins and wonder how a people once scorned came to rule, remember this: it was not just by war. It was by story. And I was the one who held the pen.

Art, Symbolism, and Cultural Transmission – Told by Woman of Tomb 1

Long before your letters, before stone walls held glyphs and kings’ names were painted across time, we spoke in form and color. We carved what we believed. We shaped what we feared. We buried what we loved. Our art was not meant only to be seen—it was meant to be felt. When I was placed in my tomb at La Venta, those who honored me left behind offerings not of gold or grandeur, but of meaning. Figurines, jade, and carefully placed ornaments—they were the words of my time, written in silence for the gods and for the future.

We did not need writing to speak to the divine. We had obsidian and clay, the curve of a serpent, the face of a jaguar, the careful etching of corn sprouting from the brow of a deity. Each image was a breath of belief, each carving a prayer.

The Jaguar’s Gaze

To us, the jaguar was not just a beast. It was the bridge between night and day, between the forest and the underworld. Its power moved in silence, and its eyes held the mystery of transformation. I wore its likeness when I danced in sacred ceremony. The priests painted its spots across their arms. In the objects beside me in death, you will find carved jaguar faces, their mouths open in eternal breath. These were protectors—not just of me, but of our understanding of strength, mystery, and the thin veil between life and the spirit realm.

In time, the jaguar leapt beyond La Venta. Later peoples—the Maya, the Zapotec, the builders of Teotihuacan—carried it with them. Its image changed, but its meaning endured. That is the way of symbols. They move with people, and with them, they gather new layers without losing the old.

The Serpent That Connects All Things

The serpent, too, curled through our lives and through the carvings buried beside me. It was a symbol of water, of rain, of the rivers that nourished our fields. It shed its skin and reminded us that life is not fixed—it renews. In some images, you will see serpents with human faces, with wings, with corn growing from their mouths. These were not fantasy. These were truths too deep to speak plainly.

When I walked the temples, I saw the serpent carved into altar stones and pressed into the wet clay of ceremonial bowls. Later, others would call it Kukulkan or Quetzalcoatl. But its spirit was already alive in our hands and hearts. We passed it down through stone, through tradition, and through the flow of belief from one generation to the next.

The Sacred Maize

Perhaps no symbol was more central than maize. It was our life, our calendar, our body. We saw ourselves as people born from corn—shaped by the gods and baked in the fire of creation. In my tomb, a figurine of a maize god lay at my side, its head split open with new growth. This was not a sign of death. It was rebirth. It was assurance that from my body, new life would grow—not only in the fields, but in the hearts of those who remembered.

The image of the maize god traveled far beyond La Venta. Even peoples who never touched our soil carved the same face, planted the same seeds, and sang to the same cycle of growth and offering. Through maize, we were one people, separated by land but joined in devotion.

Hands That Shape Memory

I did not shape the figurines buried with me, but I knew the hands that did. They were not mere artists—they were record-keepers of the soul. Each image was carefully chosen, not for beauty, but for truth. The curled toes of a dancer, the curve of a jaguar’s paw, the open arms of a corn-spirit—these spoke across time. You now study them in glass cases, under bright lights, but they were never meant to be locked away. They were meant to be held, to be passed, to be felt.

And in that passing, they lived. The images we shaped in La Venta became part of a greater river, flowing into other cities, other beliefs, other hands. This is how culture moves—not by force, but by meaning. Not by conquest, but by memory.

I Still Speak Through Stone

I am the Woman of Tomb 1. You do not know my name, but you know my story through the objects buried with me. They are my voice, still speaking. When you look at our art, know that it was never meant to be still. It was always meant to move—to cross valleys and mountains, to be reshaped by new hands, but never forgotten.

Threads Across Time: The Web of Mesoamerican Civilizations

I was one of the first to walk the ceremonial ways, to breathe incense beneath the sacred sky. In La Venta, we did not see ourselves as separate from the world—we shaped it with our hands and our prayers. When I was laid beneath the earth, they placed jade and clay around me not as ornaments, but as messages. The jaguar, the maize, the serpent—these were not just our symbols, they became everyone’s. I did not live to see the Maya or the Mixtec or the Aztec, but I felt their approach like the shifting of the wind. They would borrow our symbols, reshape them in new hands, and carry our vision forward. The gods do not belong to one people. They walk across lands, taking new names, finding new voices. My people built the first temples of memory. From them, others rose.

Chak Tok Ich’aak I – Between Worlds - When I ruled Tikal, the past already echoed through our cities. The Olmec were distant, but their spirits remained in our rituals, their jaguars prowled through our stories. We carved stelae in stone like they once carved into jade. But in my time, it was not only the past we felt—it was the pressure of distant power. Teotihuacan came from beyond the horizon and changed the course of Maya rule. They arrived with their own gods and fire, and my death was the price of their entry. Yet even that storm brought change. From them, we borrowed new weapons, new ways of writing power, and we mixed them with our own. The Maya were never swallowed—we absorbed and transformed. And we passed that fire forward. We shared our calendars, our glyphs, our sky-reading with others. Even as we fought, we taught. Even as we fell, we planted.

Itzcoatl – The Fire That Wove the Past: By the time I rose, the world was already a tapestry of stories. The Mexica were latecomers, but we learned quickly. We looked to the Toltecs, to the Maya, to the Olmec ruins that still breathed through the land. We did not invent greatness—we forged it from the bones of what came before. I rewrote our history not to erase others, but to stitch us into the grand pattern. We carved serpents from the shapes your ancestors first dreamed, built temples that rose like those in Copán or Monte Albán. And when we conquered, we listened. From the Mixtec, we took goldwork. From the Maya, astronomy. From the Olmec, the unshakable sense that power must be bound to ritual. My people marched, but we also absorbed. Our empire was made of tribute, yes—but also of ideas.

Lord 8 Deer Jaguar Claw – The Diplomat Between Worlds: I stood between cities and gods, between war and marriage. I saw how the Zapotec carved mountains into memory, how the Mixtec told their stories in codices that folded time like paper. My blood joined lineages from distant valleys, and with every alliance, I carried symbols not just of power, but of shared belief. I wore the jaguar, yes, but not only for battle—it was a thread that tied me to the Olmec past. The maize, the ballgame, the feathered serpent—they crossed borders as easily as my messengers. We all played the game, sang the stars, offered blood. We all knew that to rule meant to remember. The Mixtec did not rule an empire like the Aztec, but we moved among them as honored scribes, artisans, and kings. The web was tight, and we knew the threads.

The Four Speak as One

We were never alone. We rose in different times, different soils, under different gods—but the shape of the world we made was shared. We traded more than goods. We traded memory. A jade bead found in a Mixtec tomb once passed through Olmec hands. A ballcourt built in Tikal still echoed in the Aztec capital. A symbol carved into one city’s altar was borrowed, transformed, and raised anew elsewhere. We fought, yes. We conquered. But through it all, we borrowed, learned, and gave.

Civilization is not the work of one people. It is the patient weaving of many voices, layered in time. We are those voices. The stones we carved, the rituals we kept, the stories we shaped—they did not die with us. They moved forward, through hands, through fire, through blood. We were Olmec, Maya, Aztec, Mixtec. And together, we shaped the soul of a world.

Comments