4. Heroes and Villains of Ancient Africa: The Chalcolithic Era (c. 4,000 BC – c. 3,000 BC)

- Zack Edwards

- Aug 8

- 37 min read

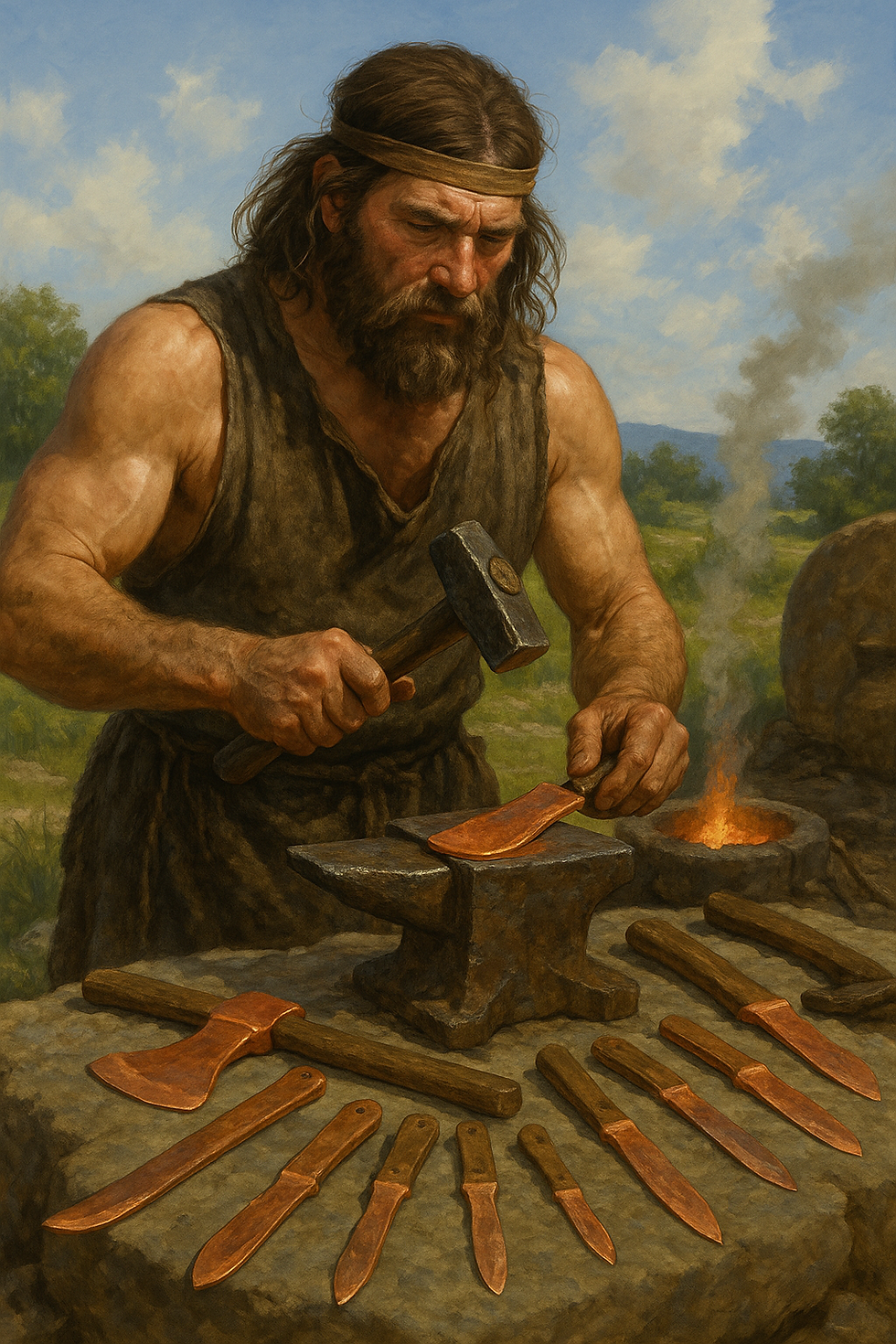

My Name is Aren: The Copper Smith

I was born into a world still ruled by stone. My father was a flint knapper, shaping blades with skill passed down for generations, and my mother worked the fields, tending barley and emmer wheat. We lived in a village near the river’s bend, where clay houses baked in the sun and smoke curled from hearths each evening. I grew up believing stone was the only way to make tools, yet even as a boy, I was drawn to the strange green stones my father sometimes found in the hills.

The First Spark of Copper

It was during a summer hunt in the highlands that I first saw molten metal. A lightning strike had set a dry slope aflame, and as we moved through the charred ground days later, I noticed small beads of red-gold glinting among the ash. We later learned the fire had melted that green stone, leaving behind copper. I could not sleep that night, imagining the shapes I might form if only I could control the heat. That thought became my life’s pursuit.

Learning the Fire’s Language

I began experimenting in secret, using clay-lined pits and bellows of goat hide to coax flame into a fierce heat. It took many failed attempts—metal that cracked, tools that bent—to understand that fire had a language of its own. Copper was softer than flint, yet could be shaped again and again. I made my first awl, then a simple blade, and finally an axe head that cut wood with a smooth, satisfying bite. Word spread quickly, and soon hunters, farmers, and even traders came to see my work.

The Road of Exchange

Copper opened the world to me. I traveled with caravans, exchanging my tools for obsidian, shells from distant seas, and dyes for pottery. In market gatherings, I saw cultures unlike my own—people with different songs, dress, and ways of worship. I began to understand that trade was more than goods; it was the meeting of minds and the sharing of ideas. My axes and blades traveled farther than I could follow, carried into lands I might never see.

The Rise of Specialists

Our village began to change. Once, everyone knew how to knap stone, but now some of us focused only on one craft. There were potters who no longer farmed, weavers who never hunted, and I, who rarely touched a plow. We depended on each other more than ever, bound together by our skills. Yet this also brought new rivalries and questions—who owned the copper, and who controlled its trade? Disputes rose as quickly as wealth.

Witness to Change

I have lived to see stone and copper share the same world, and I wonder what will come next. Some whisper of mixing copper with another metal, tin, to make something stronger. If such a thing is possible, it will change everything again. My hands are worn from shaping the red metal, my hair streaked with the gray of many winters, yet I feel my life’s work is still only the beginning. For each bead of copper I pull from the fire, I know I am shaping not just a tool, but the future.

The Birth of Copper Working – Told by Aren

I still remember the day I first saw copper freed from its stone prison. We had been hunting in the hills when a summer storm set the dry grass alight. Days later, as we walked across the charred slope, I noticed tiny beads of red-gold glinting among the ash. They were unlike any stone I had seen—soft to the touch, warm in color, and strangely alive in the sunlight. We later understood that the green stones in the hills, when kissed by enough heat, gave birth to this new metal. That moment changed the course of my life.

Learning the Fire’s Secret

At first, no one knew how to make the fire hot enough to melt the stone on purpose. I built small clay-lined pits and fed them with charcoal until the heat roared. I learned to use goat-hide bellows to push air into the flames, turning them white-hot. The green stone—malachite, though we did not yet have that name—softened and dripped into pools of shimmering copper. I shaped it into points, blades, and hooks, then hammered them to make them stronger. With each trial, I came to understand that the fire was a living thing, and I was learning its language.

Changing the Shape of Work

When I placed my first copper axe into a farmer’s hand, I saw the astonishment in his eyes. It bit into wood more cleanly than stone and could be reshaped if damaged. Hunters traded their flint blades for copper-tipped spears that pierced deeper and truer. Even simple awls for sewing hides worked faster and lasted longer. These tools allowed us to build more quickly, hunt more efficiently, and work with a precision we had never known. The village began to depend on the metal, and I became known not just as a maker, but as a bringer of change.

Copper in the Marketplaces

The demand for copper grew beyond our village. Traders came from far-off lands, offering obsidian, salt, shells, and fine cloth in exchange for tools and ornaments. Copper became more than a metal; it was a language of trade. I began to travel with caravans, my packs heavy with axes, knives, and bracelets, and returned with goods our people had never seen before. Copper linked us to distant communities, binding our lives together through exchange.

The New Edge of Warfare

Not all who came for copper did so with peaceful intentions. Warriors sought my blades to gain advantage over their rivals. A copper-tipped spear could pierce through hide armor where stone might shatter. Leaders began to gather more weapons, and disputes that once ended with shouts now ended with blood. I did not forge these tools for war, but I could not stop their use. Copper gave power, and with power came both prosperity and danger.

Why Copper Matters

I have lived long enough to see copper change the way we work, trade, and fight. It has brought wealth to our people, connected us to distant lands, and pushed us to dream of new possibilities. Yet it has also brought tension, as those without it seek to take it by force. Still, I believe the birth of copper working marks the beginning of a new age—one in which human hands can shape the earth’s gifts into whatever form we can imagine. The future will be forged in fire, and copper was our first step into that unknown.

My Name is Sila: The Hearth Keeper

I was born in a village where the fields stretched farther than the eye could see, each season painting them a different color. My earliest memories are of my mother’s hands pressing seeds into the soil and my father leading goats out to graze. From the moment I could walk, I learned that the earth feeds us only if we care for it. I carried water in clay jars, gathered kindling for the fire, and watched the rhythms of planting and harvest that bound our lives together.

The Heart of the Home

When I was old enough to tend my own hearth, I understood its true power. The fire is more than warmth or light—it is the heart that keeps a family alive. I rose before the sun to grind grain into flour, bake bread on hot stones, and stir stews that simmered for hours. The hearth was my workshop, my refuge, and my duty. Here, I taught my children not just how to cook, but how to preserve food for the long winter months, how to dry herbs, and how to keep the flames alive even through the night.

The Seasons’ Demands

Life followed the turn of the seasons. Spring meant sowing seeds in the fields and tending young animals. Summer brought abundance—baskets of berries, full milk pails, and fresh vegetables. Autumn was a time of urgency, preserving every possible scrap of food before the frost returned. Winter tested our skill and planning, when the land slept and we relied on our stored harvests. I learned to see the beauty in each season, even the cold, for it was part of the cycle that kept us alive.

A Place Among the People

Though I do not travel like the traders or work the forge like the copper smiths, my work is no less vital. When hunters return with game, they bring it to my hearth to cook for the feast. When strangers visit, I offer bread and broth before they speak of trade or news. I have seen disputes softened over shared meals, alliances born beside the fire. The hearth is where we remember who we are—not just as individuals, but as a community.

Passing the Flame

Now my hands are lined with years, but I still rise before the dawn to light the fire. My daughters and sons know the patterns of the fields, the songs for grinding grain, and the recipes handed down from my mother’s mother. I tell them that food is not only to fill the belly—it carries stories, traditions, and the warmth of those who came before. When I am gone, I hope they will remember me each time they kneel before the hearth, tending the same flame that has burned in our family for generations.

Life in Early Villages – Told by Sila

Our village rests on the curve of the river, where the water brings life to the fields and the breeze keeps the heat from settling too heavily on our homes. From my doorway, I can see the smoke rising from cooking fires, hear the bleating of goats, and smell the sweet scent of grain drying in the sun. Life here is not the roaming life of my grandparents. We stay in one place through the seasons, our homes built from mud and reed, our days shaped by the needs of the land and the rhythm of work.

The Work of the Fields

Each morning, as the sun touches the tops of the hills, we gather in the fields. The men take the heavy plows pulled by oxen, turning the soil so it will drink in the rains. The women, including myself, plant the seeds—barley, wheat, lentils—pressing them into the earth with care. We weed, we water, and we watch for pests. Harvest time is the busiest, with everyone working from dawn to dusk to gather the grain before storms can claim it. The storehouses grow full, and with them comes the comfort of knowing the winter will not starve us.

The Keeping of Animals

Our herds are part of the family. Goats and sheep graze on the edges of the fields, watched over by boys with quick legs and sharp eyes. Cattle give milk, wool comes from the sheep, and the goats give us meat when needed. The animals bring us closer to the land, for their needs are our needs. We make shelters for them in winter, and in return, they feed us, clothe us, and help us work the soil.

The Work of the Hearth

Inside the home, the hearth is my realm. It is where grain is ground into flour, where pots simmer with stews of beans, roots, and sometimes fresh fish from the river. I bake bread on flat stones, roast meat over the coals, and dry herbs for medicine and flavor. Cooking is not just a chore; it is a way of holding the family together. The fire brings warmth, the food brings strength, and the gathering around the meal brings peace after a day of toil.

The Roles of Women and Men

Men often work the plows, hunt, or trade with distant villages, while women tend the crops, raise the children, and keep the hearth alive. Yet the work of one cannot be done without the other. When men are away, women lead the planting and the harvest. When women fall ill, men take up the cooking and the weaving. The village thrives because all share in the labor, even if our tasks are different.

The Ties That Bind Us

Life in the village is not without its challenges. Crops fail, animals fall sick, and storms can undo months of labor in a single night. But we face these trials together. We help each other build homes, share food with those in need, and join hands in festivals that honor the turning of the seasons. Here, in the circle of homes and fields, life is more than survival—it is the weaving together of many lives into one enduring community.

Trade Networks and Travel Routes – Told by Aren

When I first began shaping copper into blades and ornaments, I thought only of my own people. But soon, strangers came—men and women speaking in tongues I did not know, carrying goods I had never seen. They had walked for days, even moons, to find me. It was then I understood that copper was more than a tool. It was a key to doors I had not yet imagined. To reach those doors, I would have to leave the safety of my hearth and walk the winding paths beyond the horizon.

Paths Worn by Many Feet

Trade routes are not roads carved into the earth; they are memories passed from one traveler to the next. A bend in a river, a gap in the hills, a lone tree on a wide plain—these are the markers we follow. I learned to read the land as others read a scroll. Some routes follow the rivers, where boats and rafts carry goods more swiftly than feet. Others cross high passes, where the wind bites and the air grows thin, but where rare stones and herbs can be found. Every path holds risk, yet every path leads to possibility.

The Goods We Carried

In my packs, I carried copper knives, axe heads, and bracelets, wrapped in cloth to keep them from harm. In return, I received obsidian sharper than any blade I could forge, seashells from shores I had never seen, and woven cloth dyed in colors richer than any plant in my homeland. Grain from fertile valleys, salt from far deserts, and even stories—yes, stories—were traded, for they carried value as much as any object.

The Meeting of Peoples

In distant villages, I learned that trade was not only about goods. I saw new ways of shaping pottery, heard songs that spoke of lands where the sun rises from the sea, and watched dances meant to call rain from the clouds. Each journey brought me knowledge of customs, tools, and ideas I had never known. When I returned home, I brought these with me, and our people grew richer in spirit as well as in goods.

The Bonds of Exchange

Trade binds more than the hands of the giver and the receiver—it weaves entire peoples together. When harvests failed in one place, grain from another could save lives. When conflict threatened between two tribes, trade could build trust where words alone failed. I have seen copper from my forge worn by a fisherman far to the east and by a herder in the western hills. In that way, my work has traveled farther than my own feet ever could.

The Endless Road

Even now, I feel the pull of the trade routes, the urge to see what lies beyond the next bend in the river. The world is wide, and the paths that connect it grow stronger with each step taken. Trade has taught me that no village stands alone. We are all linked—by goods, by ideas, and by the endless road that invites us onward.

My Name is Tovan: The Spirit Guide

I was born on a night when the moon was full and the river ran high from mountain rains. My mother said the spirits marked me before I could walk, for I did not cry like other infants but stared at the flicker of the fire as if listening to voices only I could hear. My father was a herder, but my path was never toward the fields or the hunt. From an early age, I wandered away to sit beneath the great stones or watch the sun slip behind the hills, feeling the breath of the world move through me.

Learning the Ways of the Ancestors

The village elder, Old Mera, saw in me what she called a “listening soul.” She took me under her care, teaching me to watch the flight of birds, to read the patterns of clouds, and to feel the shift of the wind as a message. We visited the burial mounds, leaving offerings of grain and beads, and she showed me how to speak to the spirits of those who came before us. I learned the songs that call rain, the chants that guide the dead, and the gestures that mark the turning of the seasons.

Keeper of Ceremonies

When Mera’s voice grew too weak for the long prayers, I took her place at the center of the circle. I learned to shape fire into a beacon for the night rites, to lay out stones in patterns that mirrored the stars, and to pour water over the earth to awaken life. The people came to me for blessings before a hunt, for words to guide them through sickness, and for signs before planting. I was not a chief, yet my voice carried weight in matters of where we would settle or when we would move on.

Guarding the Stories

My greatest task was to remember. The tales of the first people, the journeys from distant lands, the great floods and the years of plenty—these lived in my mind like treasures. Each winter, when the nights were long, I told these stories to the children so they would carry them forward. We carved symbols into stone and painted the walls of the sacred house with spirals, animals, and shapes of the sun, so that the stories would speak even after our voices faded.

Witness to Change

In my youth, we buried our dead in simple graves, with a few beads or a pot of grain. Now, I have seen great stone tombs raised, lined with treasures of copper, shells, and fine pottery. The people believe these offerings carry favor into the next life, and I have led many such rites. The making of copper, the building of larger villages, and the far-reaching trade have brought new power to our people, but also new questions about what the spirits demand of us.

My Path Forward

I have lived many seasons, and my hair is the color of the winter frost, yet the spirits still whisper to me in the rustle of reeds and the cry of night birds. I do not know how the world will look when I join the ancestors, but I know the circle will continue. As long as someone keeps the songs, tends the fire, and listens to the wind, the spirits will remain close, guiding those yet to come.

Spiritual Beliefs and Burial Rites – Told by Tovan

From the moment I first walked among the great stones of our ancestors, I felt the weight of the unseen pressing upon me. Life is not only what the eyes can witness or the hands can touch. There is a thread that binds the living to those who have gone before, and it is my task to tend that thread. We believe the soul does not end with the last breath but travels onward, guided by the rites we perform and the gifts we place at its side.

The Great Stone Tombs

Our dead are not left to the earth without care. We build tombs from stones so large that it takes the strength of the whole village to move them. These megalithic houses for the dead stand against the wind and rain, marking the presence of those who shaped our lives. Some are passage tombs, with long corridors leading to a chamber deep within, where the sun enters only on certain days of the year. In those moments, light touches the resting place of the ancestors, as if the sky itself is paying respect.

Gifts for the Journey

We do not send the dead into the next world empty-handed. In their tombs, we place food, tools, beads, and sometimes weapons. For a skilled hunter, I might place a copper-tipped spear; for a weaver, fine cloth or a spindle. These are not for the body, which returns to the earth, but for the soul, which we believe journeys to a land much like ours, where rivers run, fields grow, and kin await. The gifts help them begin again, strong and prepared.

The Songs and the Silence

When a death comes, the people gather. We light fires that burn through the night, and I lead the chants that guide the spirit away from the body. There are moments of weeping, and moments of deep silence, when we listen for the signs that the soul has crossed the threshold. Sometimes a bird will call, or the wind will shift suddenly, and we know the journey has begun.

What We Believe Awaits

I have been told by the elders who taught me that the afterlife is not a far-off dream but a continuation of what we know, only without pain or hunger. There, the harvest never fails, the animals never wander too far, and the fire always warms. It is a place where the ancestors watch over us, sending blessings or warnings through signs in the living world.

The Living and the Dead

Our rites are not only for the departed but for those who remain. In honoring the dead, we strengthen the bonds within the living. Each tomb stands as a reminder that we are part of a chain stretching back through countless generations. When I pour the final libation upon the stones, I feel the presence of those who came before and those yet to come, all gathered in one unbroken circle.

Art and Symbolism – Told by Tovan

Long before I learned the chants of the ancestors, I understood that not all messages are spoken. The earth itself speaks in patterns, in colors, in shapes that tell a story without a single word. Our people have always left marks upon the world—not just to please the eye, but to remind us of who we are and what we believe. Art is not mere decoration; it is a language for the soul.

The Painted Clay

Pottery is more than a vessel for grain or water. In our village, each pot tells a story. Some are painted with spirals, echoing the turning of the seasons or the path of the sun across the sky. Others bear zigzags like the ripples of the river, or dots that speak of seeds scattered in the field. When I hold a pot made by our artisans, I can tell if it was shaped for daily use or as an offering to the spirits. The colors—red from ochre, black from ash, white from ground bone—each carry meaning, each chosen with care.

Figures of the Sacred

Among our most precious works are the small figurines shaped from clay or carved from stone. Some are of animals, their strength and grace captured in a single curve. Others are human forms—women heavy with child, guardians holding weapons, dancers frozen in movement. These figures are placed in homes, fields, and tombs, watching over the living and guiding the dead. When I lead a ceremony, I often place such figures at the center, for they draw the attention of the unseen.

Marks of Belonging

Art also tells others who we are. Patterns unique to our village mark us in the eyes of traders and visitors. A man wearing a pendant with our spiral-and-sun symbol is known to be of our people, even in a distant land. This shared imagery binds us together, reminding us that we are part of something larger than ourselves.

The Hidden Meanings

Not every pattern is meant for all eyes. Some are sacred, shown only during certain rites or to those who have earned the right to see them. These designs carry teachings, warnings, or blessings that must be guarded. I have seen strangers admire a pot for its beauty without realizing the power of the signs painted upon it. In this way, our art speaks in layers, revealing its truth only to those prepared to understand.

The Spirit in the Work

When the potter shapes clay or the carver chips away at stone, they are not just making an object—they are breathing life into it. We believe that each work holds a spirit, awakened by the hands of its maker. That spirit remembers the purpose for which it was created and carries it out long after the maker has gone. In this way, our art does not fade with time; it walks alongside us, whispering our stories to future generations.

My Name is Kiro: The River Hunter

I was born where the river widens and the reeds grow tall enough to hide a man. My earliest memories are of the sound of water lapping at the bank and the flash of silver as fish leapt from the shallows. My father taught me to weave reed mats for our boats and to set traps where the current runs strong. My mother taught me to read the ripples on the water’s surface, for they tell you what swims beneath. We were not farmers then, though we traded with those who were. The river gave us all we needed.

Learning the Hunt

Before I was tall enough to draw a bow, I could throw a net. I learned to track waterbirds by their calls and to spear fish in the clear shallows. In the autumn, when the deer crossed the river to find shelter, we lay in wait among the willows. My people moved with the seasons, following the herds, the fish runs, and the wild fruits. We carried our homes on our backs and built new ones wherever the land was generous.

When the Villages Grew

As I grew, the world began to change. Farmers cleared more land along the river, planting fields that stretched where once there had been wild grass. They built houses that stayed standing year after year, and smoke rose from the same hearths through all the seasons. I began to hunt less in the deep forests and more along the edges of these fields, where deer came to feed on the farmers’ grain. The river still gave us fish, but I saw fewer wild places with each passing year.

Finding New Skills

It was Aren the Copper Smith who first asked for my help to find ore in the hills. I knew the winding paths and hidden valleys better than most, so I guided him in exchange for blades and hooks of the red metal. Copper changed my work. My spears stayed sharp longer, my arrowheads bit deeper. The farmers paid me with grain to catch fish for their feasts or to drive off the wolves that circled their goat pens. My life became a bridge between the old ways and the new.

The River as a Road

In time, I began to travel far beyond my home. The river carried me to villages I had only heard of in stories. I traded dried fish, animal skins, and antler points for pottery, woven cloth, and beads of bright colors. I learned to read the currents like a map, knowing when they would speed me forward and when I would have to fight against them. The river was more than water; it was the road that bound all people together.

Keeper of the Wild

Even as the fields spread and copper tools filled the hands of many, I kept the old skills alive. I taught the young ones how to move silently through the reeds, how to tell the difference between the tracks of a fox and a wildcat, how to listen for the warning calls of birds when danger approaches. The wild still has lessons to teach, and I fear the day we forget them. The river is patient, but it remembers who respects it—and who does not. When I am gone, I hope there will still be those who rise before the sun, step into the cool water, and listen to the voice of the current.

Hunting and Gathering in a Changing World – Told by Kiro

I was raised in the way of the hunt, when the chase was not a sport but the difference between hunger and a full belly. My earliest memories are of moving through the reeds at dawn, bow in hand, feeling the breath of the earth in the cool morning mist. We knew the tracks of every creature and the seasons of every plant. The wild gave us meat, fish, berries, nuts, and roots, and in return we took only what we needed. That balance was the way of life for my family and those before us.

The Arrival of the Fields

Then came the plowed lands and the steady rows of grain. Farmers settled where once herds had roamed, fencing the earth to keep their crops safe. It was strange to see the land held in one place, as if the earth itself could be owned. At first, I thought the old ways would vanish, but I soon saw that the wild was not so easily tamed. There were still deer in the forests, fish in the rivers, and berries ripening on the hillsides. The fields changed the hunt, but they did not end it.

The New Hunts

With the farmers came new opportunities. Deer and boar were drawn to the crops, and we learned to wait along the edges of the fields, taking them before they could destroy the harvest. The rivers became busier, with nets set not just for fish but for trade. I still ranged into the deep woods for game, but I also brought back herbs, honey, and wild fruits the farmers could not grow. These became prized goods in the village markets, traded for bread, tools, or cloth.

Hunting for the Hearth

Even as farming filled the storehouses, the people still depended on what we gathered from the wild. In the harshest winters, dried venison and smoked fish kept bellies from aching. Wild greens and roots added strength to meals when the last of the stored grain began to run low. The farmers’ harvest was predictable, but the wild was a gift that could not be measured by the turning of the plow.

Passing on the Skills

I have made it my duty to teach the young how to move silently, how to read the signs of the forest, and how to know which plants will heal and which will harm. The skills of the hunt are not only for survival; they are for understanding the land itself. Even those who never leave the village should know how to find water in dry ground or food in the heart of winter.

The Wild Endures

The world is changing, and we hunters change with it. We walk the fields alongside the farmers, trade with the smiths, and share our catches at the village feasts. But when I slip into the forest or push my boat into the misty river, I know the wild still waits, unchanged in its heart. As long as there are those who seek it, the old ways will never be lost.

Domestication of Animals – Told by Sila

When I was a child, animals were something we hunted or feared. The deer were swift, the boar dangerous, and the wolves quick to take what was ours. But over the years, we learned that some creatures could live beside us, not as prey but as partners. It began with goats and sheep, creatures small enough to manage yet valuable in many ways. Slowly, they grew used to our presence, learning that we offered safety and food. In return, they gave us more than we had ever expected.

The Goats and the SheepThe goats were the first to become part of our daily life. They are clever and stubborn, always testing fences and nibbling at anything within reach. Yet they give rich milk, which can be drunk fresh or turned into cheese that lasts through the cold months. Sheep are quieter, more content to stay close, and their wool keeps us warm when winter winds blow. With these animals, we no longer had to rely only on the hunt for meat, and we could clothe ourselves in something better than rough skins.

The Power of CattleCattle changed everything. Strong and steady, they pull the plows that turn the soil for planting. Their size alone is enough to protect them from many predators, and their milk feeds families when crops fail. When a beast is slaughtered, the meat feeds the village for days, and every part is used—horns for tools, hides for leather, bones for needles and ornaments. The work they do in the fields means fewer hands are needed for plowing, freeing some to weave, build, or trade.

Shaping the SeasonsKeeping animals has given new rhythm to our lives. In spring, the lambs and calves are born, bringing joy and extra work. Summer is a time of grazing, when we move the herds to higher ground to find fresh pasture. Autumn brings the culling of animals to prepare for winter, and in the coldest months, the herds stay close, their breath steaming in the frosty air. Each season carries its tasks, and the care of animals binds us to the turning of the year.

Work Shared Between Many HandsTending animals is not the work of one person alone. Men build the shelters and drive the herds to new grazing grounds. Women milk the goats and sheep, spin wool into thread, and prepare meat for storage. Even the children help, carrying feed or watching for signs of illness. The animals are not just possessions; they are part of our community, and their care teaches patience, watchfulness, and respect for the life we share.

A Bond That EnduresThe domestication of animals has given us more than food or labor—it has given us a kind of security our ancestors never knew. The herds are a living store of wealth, a resource that grows and multiplies with care. They have changed the way we live, allowing our villages to thrive even when the wild game is scarce. As I walk among them at dusk, hearing their quiet murmurs, I know they have shaped our lives as surely as we have shaped theirs.

Irrigation and River Management – Told by Kiro

I was born beside the river, and I have never known a day when its voice was not in my ears. It feeds the land, carries the fish, and gives us a road to distant places. Without it, our fields would dry, our nets would hang empty, and our trade would wither. The river is not just water—it is the thread that holds our lives together.

Guiding the Water to the FieldsIn my youth, the farmers planted where the river flooded each year, leaving behind rich, dark soil. But the floods came when they pleased, and sometimes not at all. We learned to dig channels from the river to the fields, guiding its water to where it was needed most. These irrigation ditches meant that crops could grow even when the sky withheld its rain. It was hard work, carving through the earth with copper and stone tools, but the reward was full storehouses and a steady harvest.

Keeping the Channels AliveA channel left alone will silt up or wander from its path. We learned to walk the length of each ditch, clearing weeds, repairing banks, and deepening the bed where it had grown shallow. Sometimes we built small gates of wood or stone to hold the water until it was needed. When the channels run well, the fields drink deeply, and the crops grow strong. When they fail, hunger is not far behind.

The River’s Gift of FishThe same channels that feed the fields can also guide fish into our nets. In the shallows, we build low weirs of stone to slow the water, letting us catch them more easily. During certain seasons, the river teems with life—silver flashes of fish heading upstream, their bodies thick in the water. These catches feed not only our own people but also those in villages far from the river’s edge.

The Road of WaterBoats made from reeds or hollowed logs carry us along the river’s length. They bear our goods to markets upriver and return with pottery, grain, or rare stones from faraway lands. I have traveled for days on the water, sleeping under the stars, following the bends and branches of the river like a great winding road. Where the land is harsh, the river offers passage. Where the earth is generous, the river carries its bounty to others.

Guarding the FlowThe river gives freely, but it must be respected. Too much water taken for the fields can leave the lower villages dry. Damming the flow too long can kill the fish before they spawn. We meet with those who live upstream and down to agree on how much we each may take. These talks are not always peaceful, but they are necessary. The river belongs to all who depend on it, and its care is a shared duty.

The Ever-Moving CurrentSeasons change, villages rise and fall, but the river endures. Its waters remember every hand that shaped its banks, every net cast, every boat pushed into its current. As I stand on its shore at dusk, I know it will carry my people’s life forward long after my own steps fade from its banks.

Conflict and Cooperation – Discussed by Aren and Kiro

Aren: When I was young, a village was a handful of homes clustered together, small enough that everyone knew each other’s names. Now, the land is crowded with settlements. Fields stretch farther, herds grow larger, and people press against one another’s borders. Copper tools and weapons have made it easier to build, to farm, and to defend—but they have also made it easier to take.

Kiro: The wild places I once hunted freely are now claimed by villages I have never visited. Rivers that once flowed open to all are guarded by those who live along their banks. As the people grow in number, so do the reasons for dispute—over land, over water, over game. Yet these same people also need each other, for no village can stand entirely alone.

The First Sparks of DisputeAren: I have seen arguments begin over a single stretch of fertile ground. One side claims it has always been theirs; the other says they cleared the land with their own hands. Copper has become part of these quarrels. A strong blade or sharp spear can settle a dispute, but too often, the settlement comes in blood.

Kiro: Hunting paths have been blocked, fishing spots claimed by force. I have stood in meetings where voices rose and hands went to weapons, all over a patch of riverbank. Still, I know that if the rains fail or the herds sicken, these same people will look to each other for help.

The Building of AlliancesAren: To avoid war, many villages form pacts. A marriage between families can bind two communities together. Trade agreements promise a steady exchange of goods. I have made copper tools for allies as gifts, strengthening the bonds between our people. When trouble comes, those bonds are tested—and often hold.

Kiro: Alliances are as old as the hunt. Hunters from different villages have always joined together to bring down larger game. Now, the prey is sometimes an enemy that threatens both. When two villages agree to share resources or guard each other’s borders, the land becomes safer for all who live upon it.

Defending What Is OursAren: As copper weapons spread, defense has become a greater concern. Some villages build walls of stone or earth, others dig ditches or post sentries at night. I have forged spearheads and axe blades for those who guard our homes. We do not wish for war, but we must be ready if it comes.

Kiro: In my travels, I have seen patrols along riverbanks, and lookouts posted on high ground to watch for strangers. A strong defense is as much about showing you are prepared as it is about fighting. Often, an enemy will think twice if they see that your people stand ready together.

The Balance Between Strife and PeaceAren: We live in a time where the power to destroy and the power to unite grow side by side. I have seen copper blades drawn in anger, but I have also seen them exchanged in peace. It is the choice of the people which path they follow.

Kiro: The land is wide, yet it feels smaller now, with so many villages and so many eyes watching the same resources. Conflict is easy to find, but so is cooperation—if we remember that the river flows for all, the game runs for all, and the seasons turn for all. Our survival depends on both the courage to defend and the wisdom to join hands when the time is right.

The Legacy of the Chalcolithic – Told by All

Aren: When I think of the days before copper, I see a world slower, bound by what stone could shape. Now, we have learned to draw metal from the earth, to mold it with fire, and to trade it across lands we once thought distant. Copper has given us sharper tools, stronger weapons, and goods worth carrying to the farthest markets. I believe this was the first step toward something greater—metals yet unknown to us that will shape even mightier tools.

Sila: The changes have not been only in tools, but in the way we live. Our villages are larger, our homes stronger, and our fields better tended. Herds give us steady food, wool for clothing, and labor for the plow. This new life binds us together in ways the wandering life never could. We stay in one place, we build upon what came before, and we leave behind something for those who will follow.

The First Threads of ComplexityTovan: I see the legacy of this time in the patterns of our lives and in the stones of our tombs. We now raise monuments that speak to those not yet born. Our art carries the symbols of our people, and our rites carry our beliefs across the generations. These are not the works of scattered families, but of communities united in purpose. It is the order and cooperation of many hands that allow such works to rise—and such order will be the foundation of greater cities to come.

Kiro: I have walked from one river’s mouth to another, from highlands to coastal plains, and I see the same pattern repeating. Villages are linked by trade, by marriage, and by the need to share water, game, and pasture. This web of connections means that no place stands entirely alone. It is harder for one village to vanish without trace, for its knowledge and ways are carried outward along these paths.

The Roots of the FutureAren: Copper has taught us to look deeper into the earth for what it can give. If we can turn green stone into red metal, what else might be hidden below? The skills we have learned—smelting, casting, shaping—will not be lost. They will lead us to stronger metals and finer crafts, to tools that can cut harder stone and build larger homes.

Sila: Farming and herding have taught us to store more than we need for a single season. With full storehouses, people are free to spend time on work other than survival—crafting, building, trading. This freedom will let us grow settlements larger than any we know now.

Tovan: Our beliefs and customs now reach beyond the family to the whole community. In the future, such shared identity will hold even larger groups together, binding them not by blood alone, but by common purpose and vision.

Kiro: The roads and river paths we use today will one day lead to places we cannot yet imagine—markets so large they will seem like cities themselves. The skills of travel, trade, and cooperation we have learned now will guide those who walk them in the centuries to come.

The Age Yet to ComeAren: We do not yet know the name of the age that will follow ours, but we can feel its shadow ahead of us. The tools will be stronger, the buildings taller, the villages greater in number and size.

Sila: Those who come after will not see our lives as simple, but as the roots of their own. The work we have begun will grow into things we cannot dream of.

Tovan: They will stand in wonder at our stones and our art, just as we honor the work of those before us.

Kiro: And they will walk the same rivers, the same paths, knowing that their journey began here, in our time—the Chalcolithic, the bridge between the old world and the one yet to be.

Architecture and Settlement Layout – Told by Sila

When you live in one place through the turning of many seasons, your home must be strong enough to endure sun, wind, and rain. We build our houses from what the land gives us—walls of packed mud or clay mixed with straw, roofs of woven reeds, and wooden frames cut from the nearby groves. Some are small, built for a single family, while others hold more than one generation under the same roof. The walls stay cool in the heat of summer and hold warmth in the winter, a comfort after long hours in the fields.

The Shape of the VillageOur homes form a circle or cluster, facing inward toward the open space where life gathers. This arrangement keeps us close, allowing neighbors to see one another’s fires at night and watch for any danger. Narrow paths wind between the homes, leading to the fields, the river, or the animal pens. In some places, the outer ring of homes serves as a shield against the wind or unwanted visitors, with only a few narrow openings leading out.

The Heart of the CommunityAt the center of the village is our meeting place. It may be nothing more than a wide, packed-earth square, but it is where all voices can be heard. Here we share meals during the harvest, hold ceremonies, and listen to the words of leaders or spirit guides. It is where disputes are settled, where visitors are welcomed, and where news from distant places is shared.

Work Spaces and StorageAround the village, you’ll find spaces set apart for specific tasks—pottery kilns near the clay pits, looms in shaded corners, and grinding stones for turning grain into flour. Storehouses stand on raised platforms to keep the grain dry and safe from pests. These are tended by those chosen to guard the village’s food, for the well-being of all depends on what is kept within.

Living Together as OneThe way our homes are built and placed is not just about shelter—it shapes the way we live. We see one another daily, share tools and labor, and come together in the center for work and for joy. A village is more than its walls and roofs. It is the joining of many lives into one place, bound together by the paths we walk between our doors and the fires we gather around at day’s end.

Clothing and Textile Production – Told by Sila

The clothes we wear begin their life long before they touch our skin. In spring, when the sheep shed their heavy winter coats, we shear the wool, washing it clean in the river before spinning it into thread. From the fields, we gather flax, pulling it up by the roots and soaking it until the fibers loosen from the stalk. These are the gifts of the herd and the land, and they are the beginning of all that we make.

The Work of HandsSpinning wool or flax into thread is slow work, but it carries a rhythm that soothes the mind. We twist the fibers between our fingers, drawing them into long, even strands before winding them onto spindles. Once we have enough thread, we weave it on simple looms, passing the shuttle back and forth, creating cloth that is both strong and supple. Each length of fabric is the work of many days, and we handle it with care.

Colors of the EarthOur cloth is rarely left plain. From berries, bark, roots, and leaves, we draw colors—reds from madder, yellows from certain flowers, deep browns from the husks of nuts. Wool drinks in these colors best, holding their brightness through many seasons. Dyeing is more than making something beautiful; each color carries meaning. Some shades are worn in ceremonies, others mark a time of mourning, and still others are used only by certain families.

Patterns That SpeakWeaving is not just about making cloth; it is about telling a story. Patterns of stripes, checks, or repeating shapes show where a person comes from. In my village, a diamond pattern woven into the hem marks a married woman, while wide horizontal bands are worn by those who work the fields. These designs are passed down through generations, each carrying the history of the hands that first shaped them.

Clothing as a SignWhat a person wears tells much about them. The copper smith may wear a tunic dyed in deep red to mark his skill and standing. The spirit guide’s garments are often adorned with beads and charms to honor the ancestors. A hunter’s cloak might be lined with fur to show his success in the chase. Even the simplest garment speaks of a person’s place in the village and the work they give to the community.

The Cloth of Our LivesWhen I run my hands over a finished garment, I feel more than the softness of the wool or the smoothness of the flax. I feel the seasons that fed the sheep, the hours bent over the loom, and the laughter shared while dyeing cloth in the sunlight. Our clothing is more than protection from the wind and cold—it is the woven memory of our lives, carrying the story of who we are with every thread.

Long-Distance Trade Expeditions – Told by Aren

There came a time when the copper I shaped was no longer enough for the markets close to home. Traders began to speak of far-off places where the metal was rare, where people would give treasures in return for a single blade. I felt the pull to see these lands for myself, to carry my work beyond the familiar paths and learn what lay past the horizon.

Preparing for the JourneyA long journey begins with careful planning. I gathered not only copper tools and ornaments but also goods to trade along the way—grain, dried meat, and fine pottery. We traveled in small groups for safety, each person carrying what they could and knowing the skills they could offer. I studied the stories of those who had gone before, memorizing where to find water, where to camp, and where danger might lurk.

The Roads We FollowedWe followed the great river until it narrowed into swift channels, then crossed the hills along paths worn by countless feet before ours. Sometimes we joined coastal traders, their boats laden with shells, salt, and fish. Other times we crossed dry plains, guided by the stars and the shapes of distant mountains. Each route had its own rhythm—some slow and steady, others full of obstacles that tested our patience and strength.

Dangers Along the WayThe road was never without risk. There were bandits who saw our packs as an easy prize, sudden storms that swelled rivers into deadly torrents, and stretches of land where water was scarce and the sun burned without mercy. Once, we lost a pack animal to a hidden pit in the desert and had to divide its load among the rest of us. Every traveler learned quickly that survival depended on the group, and that one person’s misfortune could become everyone’s burden.

The Wonders We FoundYet the dangers were matched by wonders. I saw seas so wide the far shore vanished from sight, mountains capped with snow even in summer, and markets filled with goods I had never imagined—amber that glowed like trapped sunlight, spices with scents that clung to the air, and fabrics so fine they slipped through the hands like water. Every new place brought new skills to learn, new tools to study, and new designs to bring home.

The Return HomeWhen I returned from such journeys, the village would gather to hear my stories. I brought not only goods but knowledge—of distant peoples, new ways of working copper, and trade partners who might one day be allies. The paths we took became easier for those who followed, and the goods we carried wove our village into the fabric of a much larger world. For me, the reward was not only in what I brought back, but in knowing I had walked where few from my home had ever set foot.

Social Roles and Leadership – Told by Tovan

A village is like a woven cloth—each person a thread with their own work, yet all bound together into one whole. Some tend the fields, some work the herds, some shape tools or carry goods to trade. My role is to keep the stories and lead the rites, but even I depend on the skills of others. Within this cloth, certain threads stand out, guiding the rest. These are our leaders.

How Leaders RiseA leader is not chosen because of birth alone, though some families carry long traditions of guiding the village. True leadership is earned through wisdom, fairness, and the ability to see beyond one’s own needs. A skilled hunter who feeds many mouths, a trader who brings wealth from far lands, or a healer whose remedies save lives—any of these may be called to lead. The people give their trust to those whose actions have proven their worth.

The Authority They HoldA leader’s strength comes not from command alone, but from the respect of the people. They speak in gatherings at the heart of the village, listening to all before giving judgment. Their words carry weight because they have walked the same paths, shared the same hardships, and shown that their choices benefit the whole, not just themselves. A leader who loses the trust of the people soon finds their voice no longer followed.

Settling DisputesQuarrels arise in every community—over land, over animals, over the use of the river. When tempers flare, the leader calls both sides to speak in front of the village. I, or another elder, may be asked to witness and remind the people of past agreements. Often the solution is a trade, a shared use of the resource, or the setting of clear boundaries. These decisions are not rushed, for haste can plant seeds of greater conflict.

Avoiding the Path of WarWar is the last choice, for its cost is high and its wounds long to heal. Leaders work to bind villages together with marriage, shared festivals, and trade. A village that eats together and works together is less likely to take up arms against itself. Even with outsiders, it is better to exchange goods than blows, for trade brings lasting benefit while war brings only loss.

The Balance of PowerLeadership is a burden as much as an honor. Those who guide must carry the weight of every decision, knowing it will shape not only the present but the seasons to come. I have seen great leaders bring peace for a generation, and poor ones lead a people to ruin. The legacy of our leaders is carved not in stone, but in the memory of how they treated their people, and whether they left the village stronger than they found it.

Health and Healing – Told by Sila

In our village, health is the work of many hands. We have no magic that keeps sickness away, but we have knowledge passed down through generations—knowledge of plants, clean water, and rest. When someone is injured or falls ill, the whole household changes its rhythm. Work slows, food is brought to the hearth, and someone is always nearby to tend the sick.

Herbal RemediesThe earth gives us what we need if we know where to look. Willow bark eases pain, garlic wards off infection, and certain leaves draw the heat from a wound. We dry herbs in summer so they are ready when winter’s cold brings coughs and fever. These remedies are not taken lightly—each plant has its strength and its danger, and only those who have learned from the elders know how to prepare them safely.

The Work of MidwivesWhen a child is ready to be born, the midwife is called. She has hands both strong and gentle, and eyes that can see trouble before it becomes danger. Birth is a time of both joy and risk, and the midwife carries the responsibility for two lives at once. She uses herbs to ease the mother’s pain, warm water to cleanse, and soft cloth to wrap the child. The whole village listens for the first cry, knowing it means life has entered our circle.

Healing from InjuryInjuries come from the fields, the hunt, and sometimes from accidents in the home. A deep cut is washed with boiled water and bound with clean cloth. Broken bones are set with splints made from smooth branches. The healer checks the wound each day, watching for signs of fever or swelling. The patient is fed well, for strength comes not only from medicine but from nourishment.

The Role of the CommunityHealing is never the work of one person alone. The family provides food and comfort, neighbors bring what is needed, and children take on extra chores. A sick or injured person is not left to suffer alone; their recovery is tied to the well-being of us all. When someone returns to work after a long illness, it is a cause for quiet celebration, for they have been given back to the village.

The Wisdom We KeepOur ways may seem simple, but they have kept our people alive through many seasons. Every remedy, every practice, is born of long observation and care. We know which plants grow after the spring rains, which herbs lose their strength if gathered too soon, and which should never be taken together. Health is a fragile gift, and in our village, it is guarded as carefully as the stores of grain that carry us through the winter.

Comments