4. Heroes and Villains of the Age of Exploration: The Journeys of Christopher Columbus – Part 2

- Zack Edwards

- Aug 7

- 37 min read

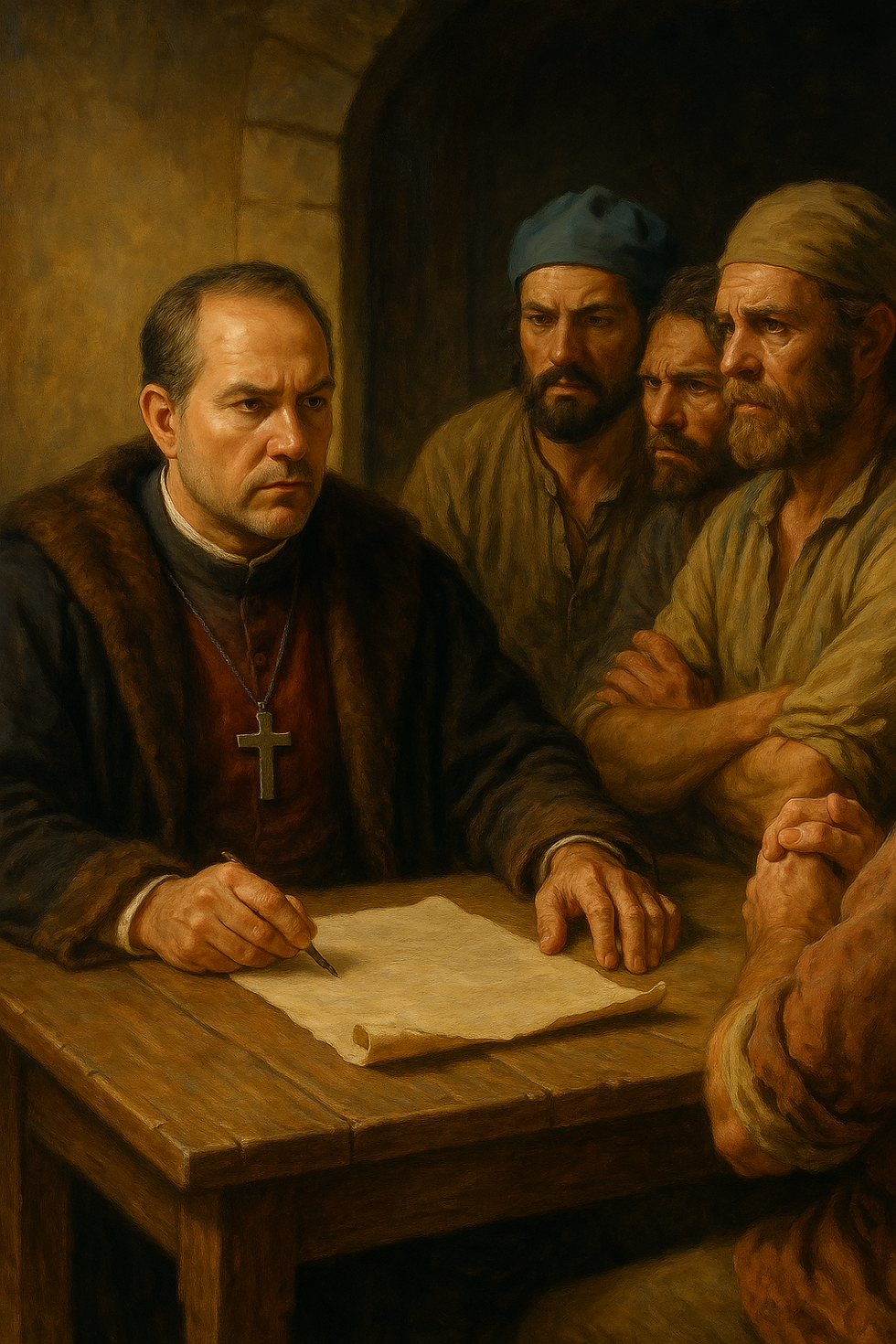

My Name is Francisco de Bobadilla: The King's Investigator of Columbus

I was born in Castile in the mid-15th century, a son of noble blood but not of great fortune. Like many of my class, I found my path not through inheritance, but through service. I entered military and royal service with a sense of duty and discipline. My life was shaped by loyalty to the Crown, and I earned trust not with grand speeches but by doing what was asked of me, quietly and precisely. Spain, under Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand, was rising. We had cast out the Moors, united the kingdoms, and now we were turning toward the vast sea. When the monarchs needed a man of authority, firm hand, and incorruptible loyalty, they turned to men like me.

Called to the Indies

In 1499, troubling reports came from the Indies—letters filled with complaints about the governance of Admiral Columbus and his brothers. There were accusations of cruelty, rebellion, mismanagement, and favoritism. The Queen and King, though proud of Columbus’s discoveries, were concerned about the growing unrest in the colony. The Indies were no longer just a place of wonder; they were a Spanish province in need of law and order.

So in 1500, Their Majesties appointed me as Judge of the Royal Court and Governor of the Indies, granting me full authority to investigate and, if necessary, to take control. I was given not just a title but the royal mandate to act on behalf of the Crown. It was not an honor I sought—but I accepted it without hesitation.

Arrival in a Land of Confusion

When I arrived in Santo Domingo, I found the colony divided. The settlers, many of whom had suffered hunger, injustice, or exploitation, welcomed my arrival. They had lost faith in Columbus and his brothers. Diego held the fort. Bartholomew governed the people. Christopher, the Admiral, was absent—exploring the island’s interior or managing disputes far from the town. The rule they imposed was not what the Crown had envisioned. Discipline had eroded. Justice was uneven. Even Spaniards complained of harsh punishments and favoritism toward foreign-born men.

I listened, I questioned, and I gathered testimonies. I had no interest in silencing one side or exalting the other. My task was to determine truth and restore royal authority. It became clear to me that the colony needed a new hand.

Arresting the Admiral

Though it grieved me, I exercised the authority granted to me and arrested Admiral Columbus and his brothers. I did not do so lightly. I respected what the Admiral had accomplished—his courage, his discoveries—but he was no longer fit to govern. His vision had become a burden to the Crown, and the people of the Indies no longer trusted him.

I placed him in chains and sent him back to Spain. Some say I shamed him, but I followed protocol. Even great men must answer to the law. He was treated with the dignity afforded to a nobleman. The Queen was moved when she saw him in chains and ordered his release, though he would never again govern the Indies.

My Brief Rule and Return to Spain

For a short time, I served as governor. I worked to restore order, reaffirm the laws of the Crown, and bring justice to the land. But I was not meant to remain. I was a judge and soldier, not a long-term administrator. In 1502, Nicolás de Ovando arrived with a massive fleet and was appointed as my successor. I stepped aside without bitterness. My work was done. I had carried out my duty with firmness and loyalty. The Crown’s authority was restored.

A Final Voyage

Not long after, I joined a fleet returning to the Indies. Perhaps I still wished to serve, or perhaps fate called me back across the sea. But I did not reach land again. The fleet was struck by a hurricane near Hispaniola, and I perished with many others in the storm. Interestingly enough, before I left, Columbus returned back in Hispaniola and sought harbor because of an impending hurricane that was coming. We denied him safe harbor, but maybe we should have listened to his weather prediction. Because I never returned to Spain, my name faded from the records, remembered only in relation to the man I was sent to investigate.

Unmasking the Admiral: My Investigation of Columbus - Told by Bobadilla

When I arrived at the port of Santo Domingo in the summer of 1500, I did not come with swords drawn or intentions set. I came quietly, bearing letters sealed by Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand, authorizing me to investigate reports of disorder in the Indies. Yet even before I reached the governor’s hall, the signs of unrest were clear. Spanish settlers, some in rags, others with fire in their eyes, met my ship as it docked. They did not whisper—they shouted. Cries of injustice, corruption, imprisonment, and even torture spilled from their mouths like floodwaters that had long been held back. They begged me to listen, to take control, to deliver them from the mismanagement. Their desperation startled me. I expected complaints. I did not expect open revolt in spirit.

The Columbus brothers—Christopher, Bartholomew, and Diego—were not present together when I landed. The Admiral himself was inland. Bartholomew, his brother, ruled in his absence. He hesitated to hand over power, even with the royal seal in my hand. I had to read the Crown’s orders publicly in the plaza, where the settlers erupted in cheers. Only then did authority begin to shift. That was the moment I realized the depth of the crisis.

The Testimonies of the Broken

I began my inquiry with calm, not force. I called for witnesses—Spaniards of every rank and station, even friars and former allies of Columbus. What I heard left no room for neutrality. Dozens, then hundreds, testified that Columbus had governed with erratic judgment and a harsh hand. He had imposed public floggings, chained settlers for minor offenses, seized property without cause, and allowed—or perhaps turned a blind eye to—brutal punishments ordered by his brothers. Men were hanged for dissent. Women were beaten for speaking against officials. Even royal officials sent from Spain had been imprisoned if they questioned his rule.

The colony was filled with fear and resentment. Some claimed that Columbus had shown favoritism to Genoese and foreign-born allies. Others said he hoarded gold or underreported it to the Crown. I listened carefully, knowing that not all complaints were honest—some were born of envy or failure—but the volume and consistency of the testimonies were overwhelming.

Meeting the Admiral

When I finally met with Christopher Columbus, he was worn, sun-darkened, and visibly exhausted. He greeted me not as a criminal, but as a man clinging to what remained of his authority. He tried to explain away the charges as misunderstandings, slanders from men jealous of his success, and troubles beyond his control. He spoke of betrayal, of a colony built from nothing, of the burdens he bore on behalf of the Crown. I listened. He did not beg, but he did plead. And I saw something else in his eyes—not guilt, but a man who had been crushed by the weight of his own dream.

Still, the law was clear. My duty was not to show sympathy, but to protect the name of the Crown. I placed Columbus, Bartholomew, and Diego under arrest—not with violence, but with formality. I allowed them dignity, even as I had them shackled. The Admiral asked that the chains never be removed until he stood before the Queen herself. I honored that request.

Intentions and Judgment

There are some who say I arrested Columbus out of ambition, that I sought to replace him, to stain his name for my own advancement. That is a lie. I had no desire to govern the Indies beyond what was required. I had no personal quarrel with the Admiral. My only intention was to serve the monarchs faithfully and uphold justice in a land far removed from their sight. What I found was not a monster, but a man who had lost his way—too isolated, too burdened, too far from correction for too long.

My investigation was not a betrayal—it was a response to betrayal, from those who had placed faith in his leadership and found it cruel or careless. I did not arrive with judgment already formed. The colony itself formed my conclusions with its own voice.

What the Chains Represented

When Columbus boarded the ship for Spain in irons, I knew the gesture would echo through history. But it was not a gesture of humiliation. It was the moment when discovery gave way to empire, and the empire reminded even its boldest servant that authority flows from the Crown, not the sword, and not the sea. My report traveled with him, along with countless letters from colonists and officials. I expected judgment to follow from the throne, not from me.

I returned to my duties quietly, not expecting thanks. I had seen the broken backs of laborers, the tear-streaked faces of families who had left Spain for hope and found horror. I had seen, too, the ruins of dreams that once lit the eyes of Christopher Columbus. And I did what the Crown required. Nothing more. Nothing less.

I am Francisco de Bobadilla. I did not set out to destroy a legend. I simply arrived to see what the truth had become. And I carried it home.

My Name is Bartholomew Columbus: In the Shadow of the AdmiralI was born in Genoa, Italy, likely sometime in the early 1460s, a younger brother to Cristoforo—whom the world now knows as Admiral Christopher Columbus. Our family was humble, rooted in wool-working and trade, but even as boys, we were drawn to the sea. While Christopher sought ships and fortune early, I chose maps. I trained as a cartographer in Lisbon and gained work in the court of France, sketching coastlines and imagining what lay beyond them. Like my brother, I believed the world was broader than the scholars said. And like him, I grew restless at the limits others accepted.

The Dream of the West

It was Christopher who carried the dream of reaching Asia by sailing west. While he petitioned monarchs and endured rejection, I continued my cartographic work, helping refine the routes and maps that guided his thinking. I acted as his anchor and his advocate when I could, traveling to England on his behalf when the Portuguese and Spanish courts hesitated. I believed in his vision—not just as a brother, but as a navigator. In time, Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand granted him the ships he sought. He sailed without me in 1492, but I knew my time would come.

To the Indies at Last

I joined my brother in the New World during his second voyage in 1494. By then, he had already tasted fame and frustration. He welcomed me to the colony on Hispaniola, and I was appointed his second-in-command. I helped establish fortresses, govern settlements, and maintain order among unruly settlers and increasingly wary native leaders. The land was beautiful, but it did not yield gold easily. Hunger, conflict, and disobedience spread. My brother was not always patient, and I—though firmer in command—had no easy solutions either.

In his absence, I governed as adelantado, or deputy governor. It was a difficult role. Spanish settlers resented our authority. I led expeditions into the interior, subdued revolts, and captured caciques who resisted. Some called me ruthless, but I believed I was enforcing Spanish rule in a wild and hostile place. I fought to hold together a colony slipping into disorder.

The Fall of the Columbus Brothers

By 1500, the colony was fracturing. Accusations flooded the royal court—against Christopher, against Diego, and against me. We were accused of tyranny, cruelty, corruption, and favoritism. When Francisco de Bobadilla arrived with royal authority, he took no time in stripping us of power. I was arrested and chained, along with my brothers, and sent back to Spain. It was a blow I did not expect, especially after all we had built. Yet we bore it in silence. I saw Christopher weep—but he never asked for his chains to be removed. We believed our service to the Crown had earned more loyalty than we were shown.

A Quiet Return and Final Years

Though the Queen received us kindly and released us from disgrace, we never again held the same power. Christopher sailed once more, but I remained behind to manage what affairs I could. The world was moving on. New governors were sent. New maps were drawn. My role faded with each passing ship. I lived long enough to see my brother die in 1506, weary and misunderstood. I, too, faded from the great chronicles. I had followed my brother into the unknown and helped hold the empire’s fragile roots in foreign soil. But I was not the dreamer—I was the builder, the enforcer, the brother left standing in the wind.

What I Leave Behind

I am Bartholomew Columbus. History may remember me only as the Admiral’s brother, but I walked the same shores, faced the same storms, and bore the same chains. My hands helped build the first Spanish cities in the New World. My maps helped shape the routes across the Atlantic. And my choices, for better or worse, were made to preserve the Crown’s hold on a new continent. I served, I ruled, and I fell. But I was there at the beginning, when the ocean opened its gates, and we dared to cross.

Alliance and Chains: The Taino and the Rise of Servitude – Told by Bartholomew

When I first arrived in Hispaniola in 1494 to assist my brother, the Admiral, I found a people unlike any I had known. The Taino welcomed the Spaniards with open arms. They gave freely—food, shelter, labor, even companionship. Their leaders, especially Guacanagaríx, treated us as guests, and we treated them, at first, as allies. My brother believed they would become good Christians and loyal subjects of the Crown. I believed they could become partners in building the foundations of Spain’s empire in the New World. In those early days, we worked side by side, erecting forts and planting crops. Their help made survival possible.

The Demands of a Colony

But peace is not easy to keep in a land of hunger and gold. The settlers who arrived were not men of patience. They had heard rumors of riches and expected a paradise. When they found labor instead of luxury, they grew bitter. Supplies from Spain were slow. The Crown demanded tribute, and the colony demanded labor. So we turned, again and again, to the Taino. At first, we asked for help gathering food or building shelters. Then we began organizing them into work groups, sometimes under their own leaders, other times under our command. What began as service soon became obligation.

The first system we used was the repartimiento, a method where native labor was distributed to settlers for short periods. It was supposed to be temporary, with rest and reward. But in truth, the lines began to blur. Work became heavier. Rest became rarer. The settlers—men raised in war or poverty—saw the Taino not as equals, but as hands to use. Some treated them justly. Many did not.

From Tribute to Chains

My brother, in need of order and gold, instituted a tribute system. Each native was required to deliver a certain amount of gold or cotton at regular intervals. Those who could not—often because they had no gold near their villages—were punished. Some fled into the mountains. Others resisted with arms. We, in turn, struck back. Rebellions were crushed. Villages burned. Captives were taken. I myself led campaigns to subdue hostile groups, believing it necessary for the survival of the colony. Yet even then, I could see the weight growing on the backs of those we once called friends.

Over time, encomiendas replaced repartimientos. These were royal grants giving settlers the right to demand labor from native communities. The Crown said it was for their Christian instruction, for their civilization. But it was slavery in all but name. The Taino worked in mines, in fields, on roads. They died in great numbers from exhaustion, mistreatment, and disease. I watched the once-lively villages grow quiet. Their songs faded. Their eyes dimmed. And I could not stop what had begun.

A Turning I Could Not Undo

Some say we intended to enslave them from the start. That is not true. We believed we could build a colony with their help, not on their backs. But greed, fear, and desperation changed everything. The settlers wanted gold. The Crown wanted order. And we—my brothers and I—were caught between promises and reality. I tried to maintain control, to govern fairly. But the tide had shifted. What began as cooperation had become bondage, and the burden fell hardest on those who had first welcomed us with kindness.

A Memory Heavy with Regret

I am Bartholomew Columbus, and I was there when the Taino first served, and when that service hardened into slavery. I cannot say we were innocent. I cannot say we were wise. I only know that the empire we built began with open hands and ended in shackles. And I will carry the memory of that turning all my days.

Clash of Authority: A Debate Between Bartholomew and BobadillaBartholomew Columbus: A Colony Built from Dust

When my brother Christopher and I came to this land, there was nothing here but trees, rivers, and wind. No walls, no laws, no bread to feed the men who followed us. We carved a settlement from the wild. We kept it alive when others would have fled. I served as adelantado, deputy governor, while my brother sailed to discover more lands. The settlers who followed us were not saints—they were fortune-hunters, thieves, malcontents. They grumbled when food was short, when gold was not found, when the natives resisted their demands. We punished only when necessary. We held order with discipline, not cruelty.

Those who now accuse us of corruption forget what the colony was and what it became. They could not endure a single month without command. Yes, there were lashings, imprisonments—but what would Bobadilla have done, had he seen the same rebellion, the same betrayal? They twist the truth, claiming tyranny where there was structure. We did not steal from the Crown. We sent ships full of gold and pearls. We governed as best we could, in a land that obeyed no rules but its own.

Francisco de Bobadilla: A Crown Ignored

Bartholomew, you call what you did discipline. I call it a kingdom forged in your family’s name, not the Queen’s. I arrived with royal authority—not by ambition, but by appointment. I did not listen to one voice but hundreds. I read testimonies of settlers jailed without trial, of Spaniards whipped in the square for speaking against you or acting cruel to the indigenous. You hoarded food while others starved. You imprisoned officials sent by the Crown. You governed with secrecy and suspicion. That is not order. That is misrule. And where was the Admiral, out island hopping instead of doing his duties.

I did not come to judge before I arrived. But the facts built themselves. You and your brothers wielded your titles like weapons, as though Spain were a banner you carried—not one you served. The settlers did not rise up because they were soft. They rose up because they were silenced. You gave yourself the power to decide who lived comfortably and who was cast into chains. That is not justice. That is corruption.

Bartholomew Columbus: You Judged Before You Understood

You speak of testimonies gathered by frightened men desperate to save their skins. Did you walk the roads we built? Did you see the forts that kept raiders away? You saw rebellion, yes—but did you ask what caused it? These men wanted gold for no labor, titles for no loyalty. They expected paradise and found hardship. And when they could not endure it, they blamed the ones who held the walls upright.

As for the prisons, yes—we held those who threatened the colony. Some were corrupt, some sowed division, some ignored orders and endangered lives. And if we refused an official’s voice, it was not to defy Spain, but to protect it from fools. You came with ink and paper. We lived among fire and hunger.

Francisco de Bobadilla: You Forgot Your Place

You may have kept the walls upright, but you turned them into a fortress of arrogance. The authority you held was given by the Crown, not forged by your brother’s discovery. And it was meant to serve the people, not dominate them. When I read the Queen’s orders aloud in the plaza, and the settlers cheered, what did that tell you? It told me the people had been waiting for the law to return.

I did not seek to replace you out of envy. I did not chain your brother for glory. I acted under orders, after careful review. You think your struggle excuses your overreach. But harsh lands do not grant a man the right to rule beyond his station. In every stone of Santo Domingo, I saw your labor—but also your pride. The Crown sent me to restore its voice. And so I did.

Bartholomew Columbus: History Will Remember Us Both

Then let history weigh our deeds, Francisco. You brought law. I brought survival. You brought judgment. I brought endurance. You saw a colony ready to bloom. I saw one ready to break. Perhaps both our truths are incomplete. But I will never regret standing by my brother. I served the Crown in the dirt, not the court. And whatever you took from me, you did not take that.

Francisco de Bobadilla: And I do not regret reminding you who truly wears the crown.

My Name is Governor Nicolás de Ovando: Order from the Crown

I was born around the year 1460 in the Spanish city of Brozas, in the province of Cáceres. I came from a noble family, one loyal to the Crown and devoted to duty. From an early age, I was trained in the ways of command and chivalry. I joined the military-religious Order of Alcántara, a brotherhood dedicated to both martial discipline and Christian service. There I gained respect for my sense of order, justice, and unwavering commitment to the authority of the monarchs. That reputation would follow me for the rest of my life.

In those years, Spain was changing. The Reconquista was nearly complete, and Spain’s attention turned outward—to trade, to faith, and to conquest beyond the seas. Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand saw in me a man who could carry their authority into these new lands. I was not a dreamer like Columbus. I was a man of structure, of command. That is why they chose me.

Appointed to Bring Order to the Indies

In 1501, I was appointed by Their Catholic Majesties as the Governor and Captain-General of the Indies. My task was clear: restore order to Hispaniola, where Columbus and his brothers had allowed chaos to grow. Reports of rebellion, mismanagement, and abuse had reached the Crown, and they desired a strong hand to replace the fractured leadership. I did not seek fame or fortune. I was sent to impose law, expand the Spanish presence, and secure the wealth of the islands for the Crown.

I sailed in 1502 with the largest fleet the Indies had yet seen—over 30 ships, carrying settlers, supplies, and soldiers. I brought with me over 2,500 colonists, many of them noble-born or experienced men. Among them was a young man named Bartolomé de las Casas, who would later speak out against the very system I oversaw. But when we arrived, there was no time for philosophy. La Isabela was failing. The gold shipments had slowed. The native peoples had begun to resist. I set to work immediately.

My Rule in the New World

I moved the seat of government to a better location and founded Santo Domingo, which would become the first permanent European city in the New World. I established laws, regulated trade, and enforced order. Roads were built, churches rose, and ships filled with gold began to return to Spain. I believed in discipline, in the power of law backed by steel.

But I must speak of the natives. The Taino people, once so plentiful, were now struggling under the weight of our arrival. I continued the encomienda system, granting Spanish settlers control over native labor. I believed, as many did, that we were bringing civilization, and that the natives—though simple in faith and culture—could benefit from our guidance. Yet I also permitted military campaigns against them when they resisted. I ordered the suppression of rebellions, and the punishments were swift. In particular, I remember the capture and execution of the cacique Anacaona, a woman of great influence among her people. I saw her as a threat to Spanish rule. Whether that was justice or fear, I will let others decide.

A Land Transformed, and the Cost of Empire

Under my rule, gold began to flow steadily into the royal coffers. Spanish towns grew, and the Catholic faith was planted firmly in the soil. But the Taino declined rapidly—killed by overwork, disease, and the sharp hand of conquest. Many say I ruled harshly, and I cannot deny that my methods were severe. But I did what I believed was necessary to secure the Crown’s interests. I did not seek cruelty—I sought control, and in those days, mercy was often seen as weakness.

In 1509, after seven years of rule, I was recalled to Spain. My task had been completed. I had brought stability to the Indies, built cities, expanded the colony, and secured its wealth. But I left behind a land forever changed—a people diminished, a continent opened, and a legacy both praised and condemned.

Reflections in Old Age

I lived the rest of my life in Spain, serving the Crown in quieter roles. I did not speak often of the Indies. Some praised me as the founder of Spanish America, the architect of order in a wild land. Others remembered only the blood and sorrow. I knew both were true.

I am Nicolás de Ovando. I was sent to bring order, and I did. But in doing so, I helped shape the empire—and also the suffering—that came with it. Let history remember both the city I built and the voices that were silenced beneath its stones.

The Crown’s Command: Why I Came to the Indies - Told by Governor de Ovando

When I was summoned to the royal court in the year 1501, Their Catholic Majesties, Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand, spoke to me plainly. The Indies were in disarray. Neither the dreamers nor the judges had brought peace to the new lands. The Crown had no interest in legends or debates. It wanted administration, order, and steady hands. I was not chosen to replace a hero, nor to avenge a wrong—I was chosen because the Crown no longer trusted either the Columbus brothers or Francisco de Bobadilla to represent it faithfully.

Bartholomew Columbus, I know what you endured. You arrived in a wilderness, faced starvation, rebellion, and betrayal. You held your brother’s vision together with blood and iron. But your rule, however necessary you believed it, became clouded by arrogance and disorder. You governed as though the Indies were the property of your family, not the Crown. That could not stand.

And Bobadilla, you came bearing royal authority, yet wielded it like a sword, not a balance. You thought justice meant vengeance, and your rapid punishments unsettled a fragile colony. Instead of healing the wound, you reopened it. Your arrival brought relief, yes—but your rule brought chaos of another kind.

I came not to side with either of you, but to restore the authority of the Crown, to build cities, and to make the Indies governable.

What I Found Upon Arrival

When I stepped ashore in Hispaniola in 1502, I found a colony swollen with greed, tangled in confusion, and deeply wounded by corruption. Bobadilla, in his effort to punish the Columbus brothers, had cast aside prudence. He handed out encomiendas—grants of native laborers—to anyone with Spanish blood and a taste for gold. He enriched the least deserving men and empowered cruelty in the name of quick stability. In truth, he treated the Taino more harshly than Columbus ever had, forcing them into labor with no protections, no guidance, and no limit. They died in the fields and mines while he counted ships full of gold dust.

He believed he was bringing justice, but he brought only exploitation. And in his rush to assert control, he allowed the very structure of the colony to rot.

Correcting the Course

I did not come with fire or favors. I came with plans. I relocated settlements to more suitable ground and built Santo Domingo into a proper city with stone buildings, paved roads, and churches. I restructured the encomienda system—not to end it, for it was the labor force we had—but to control it. I demanded that the Taino be baptized and taught the Christian faith. I ordered that their work be limited and that they receive rest and instruction. These measures were not perfect, but they were a beginning.

I worked to create a colony that could function under Spanish law, not merely Spanish ambition. I answered directly to the Crown and carried its values as best I could. Under my leadership, the colony produced wealth and order—but at a cost. I do not pretend the suffering of the Taino disappeared. Disease and overwork continued to take them. But I did what I could to discipline the settlers and restrain the worst excesses.

To Bartholomew and Bobadilla

To both of you, I say this: the Crown does not require legends or punishers. It requires governors. The Indies are not a proving ground for glory or revenge—they are a province of Spain, and they must be treated as such. You may both believe you were right, but your truths burned the same land. I came to build, not to judge you further. But let history remember that what was needed most in those years was not vision or vengeance—but governance.

I am Nicolás de Ovando. I did not arrive to win applause. I arrived to hold the Crown’s banner high, steady it in storm, and raise a city from the dust. Let that be what endures.

Ask ChatGPT

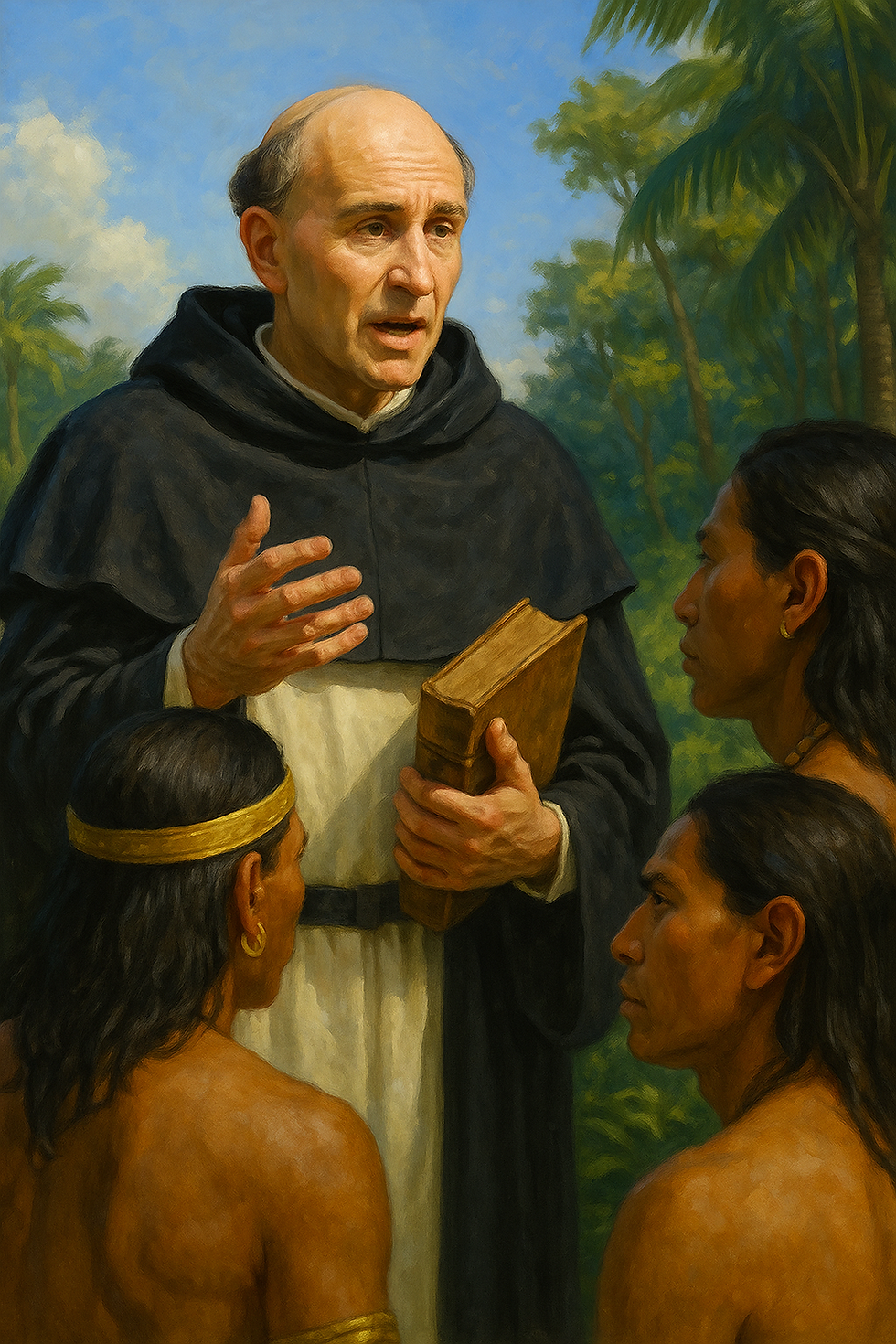

My Name is Bartolomé de las Casas: A Voice for the Voiceless

I was born in Seville in 1484, the son of a merchant who had sailed with Columbus on his second voyage. As a child, I listened to stories of the New World—of vast lands, gentle peoples, and riches waiting to be claimed. Spain was rising. We had completed the Reconquista, expelled the Moors and Jews, and were reaching beyond the seas. The air itself seemed charged with divine purpose. I studied Latin, philosophy, and law, preparing for a life of learning or faith. I did not yet know the direction I would take, only that I longed to be part of something great.

To the Indies as a Conquistador

In 1502, I crossed the ocean myself, joining Governor Nicolás de Ovando’s fleet bound for Hispaniola. I was still young, curious, and full of confidence. Like many others, I received an encomienda—a royal grant of land and native laborers. I used the people assigned to me to work the land, as was common practice. I did not question it then. I saw it as a gift from the Crown, a natural reward for service. I even defended the system in its early years, believing it could be made just. I was ordained as a priest in 1510, the first to do so in the Americas. I preached sermons, heard confessions, and saw with my own eyes the growing misery of the people around me.

A Change of Heart

It was in 1514, while preparing a Pentecost sermon, that the Scriptures struck me like a thunderbolt. The words of Ecclesiasticus—“He who offers a sacrifice from the goods of the poor is like one who kills a son before his father’s eyes”—shook me to my core. I saw the truth then: we had not come to save souls, but to crush them. The native peoples, once joyful and generous, were being worked to death, enslaved, tortured, and stripped of dignity. I renounced my encomienda and began to speak against the horrors I had once accepted. It was not easy. My fellow Spaniards laughed, grew angry, and called me a traitor. But I could not be silent.

Fighting with Words and Faith

I returned to Spain to plead for reforms. I appeared before King Ferdinand and later before his grandson Charles V. I wrote ceaselessly—petitions, sermons, treatises. My most famous work, A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, was a cry of anguish and truth. In it, I described the atrocities I had seen: children burned alive, whole villages destroyed, thousands dying from hunger and forced labor. I did not spare details. I wanted Europe to see the blood on its hands. I debated scholars, clergy, and conquistadors, arguing that the natives were rational beings with souls, not animals. I insisted that conversion must come through love, not violence.

The New Laws and the Battle for Justice

In 1542, my efforts bore fruit. Emperor Charles V issued the New Laws, which abolished the worst abuses of the encomienda system and aimed to protect native rights. I was appointed Bishop of Chiapas in New Spain, where I tried to implement these reforms. Yet resistance was fierce. The colonists resented me, and the laws were weakened within a few years. Still, I did not stop. I returned to Spain again and again, always pushing for change, always defending the innocent. I argued that slavery, in any form, was incompatible with Christian teaching.

A Troubled Conscience and Final Years

I was not without fault. In my early years, I once suggested that African slaves could replace native laborers, thinking it might ease their burden. I came to regret that suggestion deeply. I later condemned all forms of slavery and admitted my error. I lived long—until the age of ninety-two—and spent my last years in a Dominican monastery, writing, reflecting, and praying. I never stopped advocating for justice, even as the world changed and new empires rose.

What I Leave Behind

I was called Protector of the Indians, though I never sought such a title. I simply believed that all people are made in the image of God, and that no crown, no flag, no sword grants the right to destroy others. I was a priest who once accepted cruelty, then turned against it with all the fire I could muster. My words, I hope, will outlast me. I could not stop the conquest, but perhaps I helped history remember it with clearer eyes.

My Account of the Encomienda and Indigenous Labor - Told by de las Casas

I came to Hispaniola in 1502, the same year Governor Nicolás de Ovando took command of the colony. I was young, educated, and eager to claim my fortune. My father had returned from Columbus’s second voyage with glowing tales of a new world. He brought back gold, stories of strange peoples, and a sense that the Indies were a gift from God to Spain. Like many others, I saw the voyage as providence, a chance to rise in wealth and station. I was ordained as a priest in 1510, but before then, I lived as a settler among settlers. I received an encomienda—a grant of land and native laborers—and used it as others did. I oversaw Indigenous workers in the fields and took their labor in return for their supposed “protection” and instruction.

At the time, I believed the system could be just. I was wrong.

The Encomienda: A System of Chains

The encomienda system was designed, in theory, to help govern the vast population of natives we had encountered. Under the law, a Spaniard was granted control of a group of Indigenous people. He was to convert them to Christianity, protect them from harm, and teach them the ways of Spanish life. In return, they would provide tribute or labor. But in practice, it was slavery—only cloaked in the language of civilization.

The Taino and other native peoples were driven into the gold mines and fields. They carried heavy loads, dug under a merciless sun, and died by the thousands from exhaustion, disease, and despair. Women lost their children to famine, and men, once proud leaders, were reduced to beasts of burden. I watched it unfold before my very eyes, and for a time, I said nothing. I convinced myself we were doing God’s work. But I could not silence the truth forever.

The Turning of My Heart

In 1514, while preparing a sermon for Pentecost, the Scriptures cut me like a blade. I read from the Book of Ecclesiasticus: “He who sacrifices from the goods of the poor is like one who kills a son before his father's eyes.” That verse shattered my silence. I saw the system for what it was—not a partnership, but a conquest of the soul. I renounced my encomienda and began speaking out, first in sermons, then in letters, and later in books. I became a Dominican friar, devoting the rest of my life to defending the rights of the native peoples of the Indies.

The Legacy of Columbus and the Power of the Pen

Much of what we know of Columbus comes from his journals, but those journals, in part, passed through my hands. I rewrote sections of his first voyage log—at the request of others, not as a forger, but as a recorder. I tried to remain faithful, but the truth is, I may have softened some moments, emphasizing his admiration for the natives and downplaying the more violent or greedy impulses of his men. I wanted to show that the beginnings of our contact were peaceful, respectful, and full of hope. But as time passed, I came to believe that even those early writings did not tell the full truth. The first encounters were followed by hunger for gold, demands for labor, and punishments for those who resisted.

The Voice I Chose to Become

I became known as the Protector of the Indians, though I never sought such a title. I wrote A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, detailing the horrors I had seen: mass killings, forced marches, entire villages burned. I debated men of power and stood before kings, pleading for new laws to end the abuse. In 1542, some of those laws were passed, though too late to save the millions who had already perished.

I once helped build a system I would spend the rest of my life trying to tear down. I cannot erase my early silence, but I used my voice to make sure the cries of the natives were heard across Spain and the world.

I am Bartolomé de las Casas. I was a settler, a priest, a witness, and at last, an advocate. The encomienda was a mask for cruelty, and I removed that mask with ink, prayer, and sorrow. Let it never be worn again.

Dying World: Transformation of the Caribbean by Guacanagaríx and de las Casas

Guacanagaríx: A World Washed Away

When your ships first came, Las Casas, I did not see ruin. I saw strangers with bright eyes and hollow hands. I welcomed them. I gave them food, shelter, and land to rest their feet. We, the Taino, believed in the sacred balance between land and life. We took only what we needed. We danced beneath the moon. We sang to the sea. I ruled not as a tyrant but as a father to my people. I believed we could share the island. But soon, those same strangers asked for more—more food, more gold, more of our time and our strength. They took what we gave, then demanded what we never promised.

They changed the land. They cut our forests. They drove away the animals. Our rivers, once clear, were muddied by their mines and their washing pits. They brought animals that trampled our gardens and tools that carved the earth open like a wound. And our people—they no longer sang. They dug and carried, bent beneath burdens that were not theirs. Their hands, once skilled in craft and ceremony, were torn by Spanish whips and chains.

Las Casas: I Witnessed the Silence Fall

You speak true, noble cacique. I did not arrive with Columbus, but I came soon after. At first, I believed as many Spaniards did—that we had come to uplift, to guide, and to civilize. But what I found was suffering beyond measure. I saw the Taino people—the very same who had greeted us with peace—reduced to shadows of themselves. I saw villages emptied, fields overgrown, and children too weak to cry. I saw women made servants, and elders driven to dig in goldfields until their bodies broke.

And then there were the conversions. Forced, hasty, and shallow. We poured water over their heads and declared them saved, but we did not teach, we did not listen. We burned their zemis—sacred objects—without asking their meaning. We pulled their gods from their hands and gave them crosses they did not understand. Is it salvation if it comes by the sword? I asked myself that every day. I still do.

Guacanagaríx: The Songs Went Silent

Before you came, we had our own ways of speaking to the divine. We gathered in the areíto, our great dance, and remembered the names of our ancestors. Our children learned through story, through planting and fishing, through the rhythm of sun and sea. But under Spanish command, the areíto was forbidden. Our stories were called lies. Our elders were beaten for speaking of spirits. Our women wept in silence, and our children began to forget who they were.

And your priests—they spoke of a single god and eternal fire. But they did not ask why we believed in the spirits of the ceiba tree or the song of the river. They told us we were wrong before they even listened.

Las Casas: What We Called Order Was Devastation

I did not take part in the whippings or the burnings, but I shared in the sin through silence. I once held an encomienda—your people worked under my name. And I believed it just because the law said it was so. But I looked into the eyes of those who served me, and I saw not servants but captives. I saw men who had never known chains now shackled to mines. I saw women who once led their people now cooking for strangers who cursed them. And the worst part was that the killing did not come in battle. It came through neglect, through hunger, through disease, through grief.

Your people died not just in body but in spirit. You once outnumbered the Spanish by the thousands. And within a generation, you were nearly gone.

Guacanagaríx: We Gave Our Trust, and It Was Broken

Yes, Las Casas. We opened our hands and were met with iron. We were not perfect. But we had peace. We had joy. And now we are remembered only as the ones who died. Our names are carved into your histories as footnotes. Our gods are mocked. Our land is renamed. And my people—my sons and daughters—are now only ghosts to most of your kind.

Las Casas: I Carry Their Names in Ink and Tears

And yet I have tried to speak their names. I wrote of their destruction, not to flatter Spain but to haunt it. I told the kings what we had done. I told the priests. I told the world. I wrote not just of your deaths but of your lives—of your generosity, your wisdom, your dignity. You were not heathens. You were human. And the world must never forget that.

Guacanagaríx: Speak, Then. Speak Until the Wind Carries Us Again

If you truly carry our names, then do not stop speaking. Let the world remember that we were here—that we danced, we prayed, we loved, and we forgave. Let them know that the Caribbean was not empty land. It was a world of its own, transformed by sorrow, but not erased.

Las Casas: I Will Speak, Even If the Earth Itself Must Echo My Words

Then I shall go on writing, praying, and remembering. Your voice will live through mine. And perhaps one day, someone will read our story not with pity, but with understanding.

Soul of an Empire: Moral and Religious Debates - By Isabella and de las Casas

Las Casas: A Cry Raised from the Indies

Your Majesty, when I first returned from the Indies and stood once more within the halls of Spain, I carried not gold nor triumph—but grief. I came bearing the stories of a people crushed by the very men who claimed to civilize them. I had seen with my own eyes villages emptied by hunger, children orphaned by forced labor, and elders left to die in silence. I came to the court not as a rebel, but as a priest called by conscience. And I begged you, Queen Isabella, to hear what had become of the souls entrusted to our care.

Isabella: A Burden I Carried in Silence

I remember your voice, Father Las Casas. I remember the fire in your eyes. I never wished for conquest without justice. When Columbus returned with tales of new lands and new peoples, I believed it to be a gift from God—a chance to bring light to the darkness, to spread Christ’s word where it had never reached. But I also knew the dangers of unchecked power. From the beginning, I gave orders that the native peoples were to be treated with respect, baptized, and taught—not enslaved or broken. But the ocean is wide, and my commands did not always survive the crossing.

Las Casas: Baptized in Name, Broken in Body

Indeed, Your Majesty, many were baptized—but how? By force, by fear, by the lash. The settlers sprinkled water and declared them Christians, then sent them to the mines. They taught not the Gospel but the whip. A faith taught with cruelty is no faith at all. I argued before bishops, before noblemen, even before fellow priests. Some believed the Indians had no true soul. Others called them children to be guided, even if by force. I said they were men—fully human, fully capable of knowing God—not beasts or infants. That was when the true debate began.

Isabella: And I Heard Both Sides

Yes, the debates reached even my throne. Some clergy argued, as you did, that the natives were innocent, gentle, worthy of mercy and protection. Others—mostly those who had never crossed the ocean—argued that the Indians were pagans too lost to be trusted, that their sacrifice and idols proved their savagery. But you, Father, you were different. You had seen them with your own eyes, not through reports or coin-counts. And you reminded me of our higher calling. That Spain is not just a kingdom of steel—but of the cross.

Las Casas: I Tried to Teach and Rescue

Do you remember the few we brought back to Spain, Your Majesty? Young boys and men, taken from the islands to learn Spanish ways and the Christian faith. Some died from illness before they ever saw their homeland again. Others lived, studied, prayed. But when they returned, they were strangers—caught between two worlds. We tried to teach in the Indies too—through mission schools, through kind friars. Some natives embraced the teachings freely. But others had already seen too much cruelty from those who called themselves Christian to trust our words.

Isabella: It Was Never My Will to Enslave Them

And yet they were enslaved in my name. When I first heard that Spaniards were capturing natives and branding them, I issued letters forbidding it. I declared that the natives were my vassals, not chattel. I demanded they be instructed, not destroyed. But I was not always obeyed. And when I learned the truth—that even men who called themselves governors were selling souls—I wept. I gave orders, Father Las Casas. But too many men answered to greed before God.

Las Casas: The Seeds of Human Rights

Your sorrow, Your Majesty, became the foundation for something greater. It was in your court and your chapel that the first sparks of what we now call human dignity were lit. Spain, for all her sins, also became the first Christian kingdom to ask: Are these people truly men like us? Do they possess souls, wills, rights? From your throne, the question echoed across Europe. It would take decades for the answers to take shape, and longer still for justice to follow, but the question began here—with you, and with those of us who could not be silent.

Isabella: I Was a Queen, But I Was Also a Mother

I ruled with firmness, but I loved my people—those of Spain and those newly placed in my care. When I died in 1504, my greatest regret was not seeing this matter resolved. I hoped my successors would carry forward what I had begun. I hoped the Church would remember the promise of mercy. I hoped men like you, Las Casas, would never lay down their pen, nor let the voices of the innocent be lost.

Las Casas: I Spoke Because You Listened

And I have not laid it down, Your Majesty. I have written, I have preached, I have stood before kings. I remember how you listened—not as a ruler, but as a soul searching for righteousness. And in your name, I will continue to speak—for the Taino, for the Maya, for all the people whom empire tried to erase. Because a true Christian kingdom does not conquer—it lifts, it heals, and it remembers.

Isabella: Then remember me not only as a queen—but as one who tried to do what was right.

And I will, Your Majesty. Always.

The Legacy of Columbus: Hero or Villain – Debate between Chanca, Guacanagaríx, Christopher Columbus, Bartolomé de las Casas, and Queen Isabella of Castile

Columbus: I Was a Man of My Age

I sailed west not to bring sorrow, but glory. My mind burned with the maps of Toscanelli and the promise of reaching Asia by sea. I believed in my mission, that it would bring riches to Spain, and Christ to souls who had never heard his name. Yes, I made mistakes. I misjudged distances, misread signs, and perhaps trusted men who should not have been given command. But I stood on the deck of the Santa María and crossed an unknown ocean. That act—whatever followed—changed the world forever.

Chanca: I Sailed and I Watched

As the physician of the second voyage, I treated wounds, recorded what I saw, and wrote back to Spain. At first, there was wonder—the lush lands, the strength of the native people, their generosity. But soon, there was sickness, confusion, greed. Columbus tried to keep order, to rescue the Taino from their Carib enemies, but the tide of conquest was stronger than one man’s will. History may forget that he wept when he saw what some of his men had done. He was not a perfect governor, but he was not the cruelest. I believe he did not envision what followed.

Guacanagaríx: We Welcomed You

I remember your ships—wooden beasts, billowing sails. I offered you shelter, food, my trust. I believed our peoples could trade, could learn. When you were shipwrecked, I gave your men refuge. But soon, kindness became chains. Spaniards did not understand us, nor we them. They wanted our gold, our labor, and then our lives. I do not say Columbus struck the first blow, but he opened the gate. And through it came war, disease, and a sorrow that swallowed my people.

Las Casas: I Defended the Truth

I once held an encomienda. I once stood silent while others cried. But I awoke, and when I did, I could no longer defend what I had seen. Columbus, in his writings, showed affection and admiration for the Taino. He wanted peace, but could not stop the conquest. Others followed, and they did not care for souls, only for silver. Yet without Columbus, the world might have remained divided. His voyage bound continents together—but it also broke nations apart. He is not a demon, nor a saint. He is a mirror of us all—capable of vision, and of blindness.

Isabella: I Dreamed of Glory and Grace

When I agreed to fund his voyage, I did so not for gold, but for God. I hoped to spread the Gospel, to unite kingdoms, to open new roads of knowledge. I did not want enslavement or cruelty. I issued orders to protect the natives. But even a queen cannot command across oceans with perfect control. My intentions were righteous, but the results were mixed. He opened the world—and in doing so, unleashed forces we could not contain.

Columbus: I Ask, Judge Me as a Whole

History has turned me into a symbol. To some, I am a hero who bridged worlds. To others, I am the father of conquest and destruction. But I ask you—judge me as a man. I risked everything on an idea. I changed the map of the world. I made errors, yes. I failed to govern wisely, yes. But I never set out to bring ruin.

Guacanagaríx: You Were the First Storm

You say you opened the world. For us, you closed it. Our ways, our beliefs, our people—they faded beneath your flags. You may not have held the sword, but you brought it.

Las Casas: The Debate Itself Is the Lesson

Let the students ask, let them challenge. Let them learn that no history is clean. Columbus was not alone. He did not act without approval, nor did he create the systems that enslaved. But he began the exchange—of crops, ideas, animals, faith, and also suffering. To study him is to study us.

Chanca: Exploration Should Be Remembered, Not Worshipped

Celebrate the courage, the maps, the ships—but not the chains. We cannot teach only triumph. We must also teach the consequences.

Isabella: Teach the Whole Story

Let the children of tomorrow learn both the hope and the harm. Let them understand that greatness without mercy is not greatness at all.

Las Casas: And in that understanding, may they choose better.

The 4th Voyage: My Last Quest for Passage and Redemption – Told by Columbus

By 1501, my name was no longer celebrated as it once had been. Whispers of failure, of tyranny, of ambition gone sour—these clung to me like barnacles. I had been stripped of my governorship and returned to Spain in chains, thanks to the accusations of Francisco de Bobadilla. Still, I pleaded my case before Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand. I told them that my heart still beat with the passion of discovery, that the strait to the Indies—my Indies—must surely exist beyond the lands I had already seen. And though they no longer trusted me with colonies or governance, they granted me one final chance. In 1502, I was given permission to sail again—not to settle, not to rule—but to seek.

Departure and Forbidden Shores

I departed from Cádiz on May 9, 1502, with four ships: the Capitana, the Gallega, the Vizcaína, and the Santiago de Palos. My brother Bartholomew sailed with me, as did my younger son, Fernando. Our destination was the coast of Asia—or what I still believed was Asia—by way of further exploration of the southern reaches of the Caribbean. I had strict orders not to stop at Hispaniola, where the new governor Nicolás de Ovando ruled. But I also knew something others did not.

The Omen of the Sea

As we neared Hispaniola in June, I felt the winds shift and the sea groan. My experience, my intuition, and something deeper warned me of a monstrous storm brewing on the horizon. I knew a hurricane was coming. I pleaded with Governor Ovando to grant my ships shelter in the harbor of Santo Domingo. He refused. He allowed other ships, including the fleet that carried Bobadilla and many others, to set sail—laden with treasure, and arrogance.

I wrote warnings. I told the harbor masters. I left messages. And then I steered my own fleet away from the coast and into a protected cove. The storm struck with a fury I had only glimpsed once before. Twenty ships were wrecked. Bobadilla’s was lost. So too was Roldán, one of my fiercest enemies. Nearly all of the treasure they carried sank to the bottom of the sea. And I, who had been branded reckless, was spared.

To the Coasts of the Unknown

We pressed on to the coasts of Central America. I explored the shores of modern-day Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. There, I heard tales from the natives of a strait—a passage to the other sea. I believed I was close to discovering the route that would bypass the vast lands to the north and lead to the riches of the East.

We built a garrison near the Río Belén, but constant rains, disease, and conflict with the native peoples wore us down. Our ships, battered by worms and weather, began to rot beneath us.

Stranded and Forgotten

In June of 1503, two of my ships could sail no farther. We limped to the coast of Jamaica and became stranded. For a year, we survived only by the goodwill of the native islanders and by cleverness. When my sailors threatened rebellion and the locals refused supplies, I used the stars to my advantage. I consulted the lunar tables and predicted a lunar eclipse. I warned the natives that my God would darken the moon if they did not help us. When the sky went black, they came with food.

The Final Return

Relief finally arrived in June of 1504, sent from Hispaniola. I returned to Spain, not in chains this time, but broken in body. My discoveries were many, but my favor at court had vanished with the queen’s failing health. When Isabella died that same year, so too did my last true protector.

My fourth voyage did not bring me the passage I sought. It brought storms, suffering, and silence. But I had survived the seas again. I had warned of danger when others scoffed. I had sailed farther and with more resolve than any had dared before. And still, I waited for the world to understand what I had seen.

I am Christopher Columbus. My fourth journey was not a triumph, but it was a testament—to endurance, to vision, and to the tides of destiny.

Comentarios