8. Heroes and Villains of the Industrial Revolution - The Communication Revolution

- Zack Edwards

- Jul 17

- 40 min read

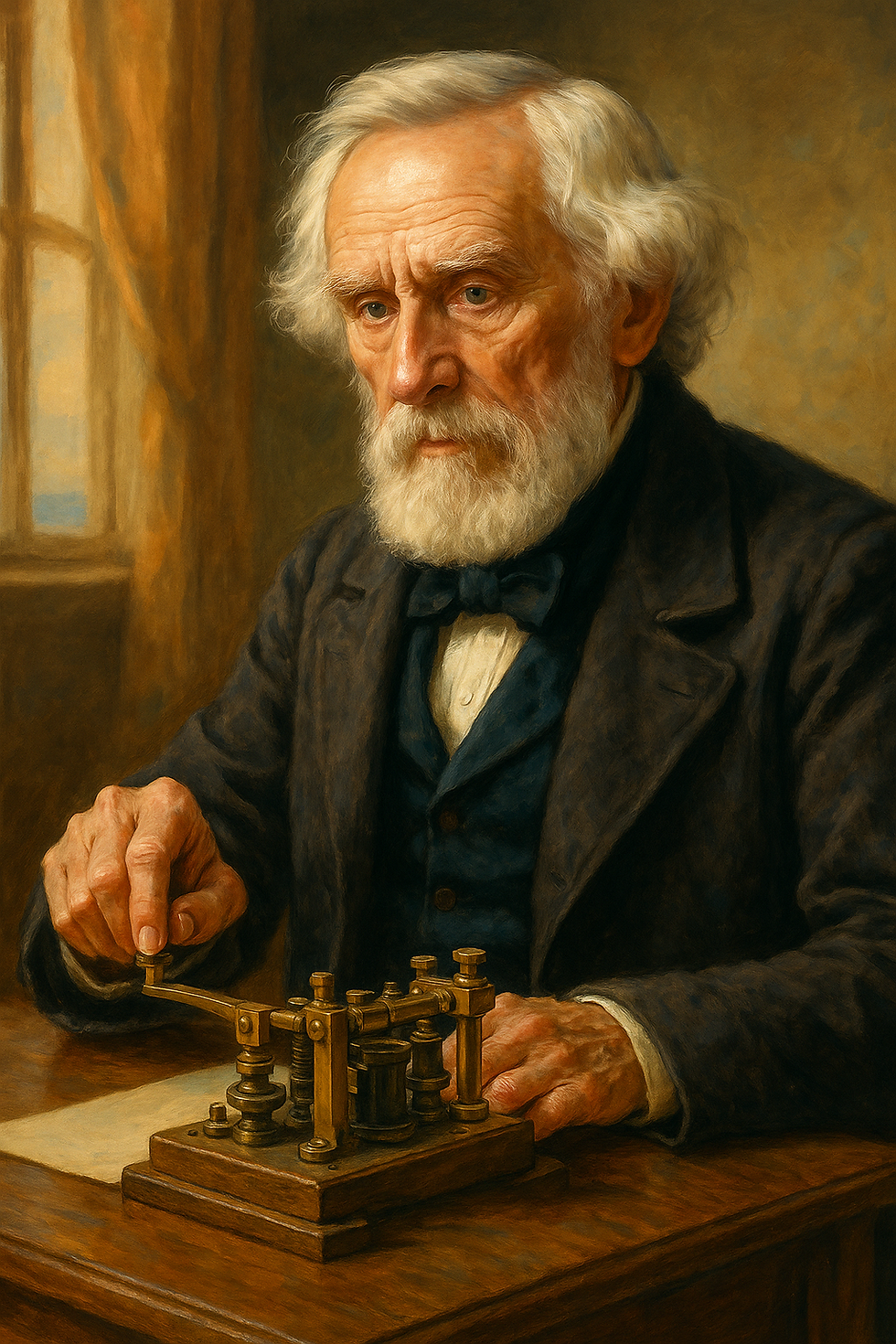

My Name is Samuel Morse: The Man Who Started to Revolution

I was born in 1791 in Charlestown, Massachusetts, the son of a clergyman and geographer. From an early age, I found myself pulled in two directions—art and invention. My father hoped I’d follow the intellectual path, and I did attend Yale College, where I studied religious philosophy, mathematics, and the newly emerging science of electricity. But while I was fascinated by science, it was art that first captured my heart. After graduation, I pursued painting with passion, studying under the great masters in England. I even painted portraits of Presidents and prominent citizens. Yet, deep within me, a spark of mechanical curiosity refused to fade.

A Tragedy That Changed Everything

My life as an artist was satisfying, but it was during a voyage home from Europe in 1832 that everything changed. I overheard a conversation about electromagnetism—how electrical pulses could travel through wires. That simple idea hit me like lightning. I became obsessed with the notion that electricity could carry messages. But what drove me even more was a heartbreak. While I had been painting a commission far from home, my wife, Lucretia, had fallen ill and died before I could return. The news came too late. I remember thinking: if only I had known sooner. If only there were a faster way to communicate.

Building the Telegraph

Driven by grief and inspired by science, I began building a machine that could send messages instantly. I envisioned a single wire system and a simple language—dots and dashes that could be interpreted into letters. But I was not an engineer by trade. I needed help. With the assistance of the brilliant Alfred Vail, who refined my ideas and built working models, we developed a working telegraph system. The road was hard. We faced disbelief, mockery, and, more than once, empty pockets. But I was persistent, and in 1843, Congress finally granted me $30,000 to build an experimental telegraph line from Washington, D.C. to Baltimore.

"What Hath God Wrought"

On May 24, 1844, I sent the first official telegraph message. Standing in the Supreme Court chamber of the Capitol, I tapped the key and sent a message chosen by Annie Ellsworth, daughter of a friend: “What hath God wrought.” It arrived in Baltimore in seconds. The crowd was stunned. This single moment opened the door to a revolution in communication. People could now send news, business transactions, even personal messages across vast distances in real time. The world would never be the same.

Legacy of the Wire

After the telegraph proved itself, lines stretched across the country and soon under the oceans. My system of Morse code became the language of wires around the world. Though others tried to claim credit, I never forgot the struggles we overcame. I wasn’t just proud of the machine—we had changed how people lived. The telegraph connected stock markets, warned of danger, reunited families, and altered the speed of war. I had once grieved that a message came too late. Now, late messages were a thing of the past.

Reflections at the End

In my later years, I was honored for my invention, even receiving tributes from kings and scientists. Still, I remained a simple man—more artist than tycoon. I never lost my faith, nor my wonder at what electricity could do. I died in 1872, knowing that my work had stitched a new thread into the fabric of humanity—one that hummed with pulses, not ink. I was not just a painter of portraits, but of possibilities. And through every dot and dash, I believe I helped the world speak a little more clearly.

Spark of Inspiration: The Invention and Impact of the Telegraph – Told by Samuel

It was during a long voyage home from Europe in 1832 that the idea first seized my mind. I had been mourning the loss of my wife, who died while I was far away, painting a portrait. The news had taken days to reach me—days too late. On that ship, I overheard a conversation about recent discoveries in electromagnetism. I asked questions, listened closely, and began to wonder: could electricity be harnessed to send messages over long distances? Could we bridge the miles in moments instead of days? That idea settled deep inside me, and I knew I would not rest until I found a way to make it real.

Designing a New Language

The first challenge was not just to send a signal, but to send meaning. I needed a way to represent letters and words using electrical pulses. So I created a code—simple, rhythmic, elegant. A system of dots and dashes, short and long signals, that could be tapped out and instantly translated by anyone who learned the pattern. Morse code, as it came to be known, was not tied to any spoken language. It was universal, mechanical, and, most importantly, fast. With each signal, a message could leap from one end of a wire to the other.

The Wire Stretches Forward

Building the device itself took years of effort, support, and partnership. I worked with Alfred Vail, whose mechanical skill turned my ideas into reliable machines. We demonstrated it in lectures, trying to win over skeptics, including those in Congress. Finally, in 1843, we secured funding to build the first telegraph line between Washington, D.C. and Baltimore. On May 24, 1844, I sent the first official message: “What hath God wrought.” It traveled forty miles in an instant. What once took couriers hours or even days now happened in the blink of an eye.

Changing the World Overnight

The telegraph caught fire across the world. Businesses used it to coordinate shipments and markets. Newspapers used it to report breaking news. Governments used it to issue commands and receive reports without delay. Railroads synced their schedules with its help. And most importantly, people could reach across cities, states, even oceans to share news, love, or warning. Telegraph wires spread across the country like veins in a living thing—then leapt across the Atlantic with undersea cables. Messages that once journeyed on horseback or steamship now traveled invisibly, in pulses of energy.

A Legacy in Every Dot and Dash

By the time I passed from this life in 1872, the telegraph had become the nervous system of modern civilization. War, trade, diplomacy, journalism—nothing was untouched. I had set out to shrink the space between people, and in doing so, helped to reshape time itself. I never imagined I’d see such speed become ordinary. But I believed, from the start, that communication could save lives, change destinies, and connect hearts. And that belief hummed in every signal tapped out in Morse code—each one echoing across the wires like a voice carried by lightning.

A Language of Signals: Morse Code and the Global Messaging – Told by Samuel

When I first began working on the telegraph, I quickly realized that sending electricity down a wire was only half the battle. The real challenge was giving that signal meaning. How could we turn electric pulses—simple interruptions of current—into language? How could a spark stand for a letter, a word, a thought? I needed to create a system that was simple, efficient, and capable of carrying the full weight of human communication. That was when I began designing what would later be known as Morse code—a language not of ink or sound, but of rhythm.

Dots, Dashes, and Precision

I studied the frequency of letters in the English language and began assigning shorter signals to the most commonly used characters. An “E,” the most frequent letter, became a single dot. Less common letters received longer combinations of dots and dashes. It wasn’t random—it was logic and efficiency. The code could be tapped out with a key, written with a pen, or even sounded through clicks. It didn’t rely on pronunciation, dialect, or spelling. It was, in its own way, pure. Whether you were in New York or New Delhi, a dot and a dash always meant the same thing.

The Rise of a New Standard

As the telegraph expanded across the United States and then the world, the need for a standardized system became urgent. Businesses were trading across borders. Armies were coordinating over vast territories. News was breaking faster than it could be printed. Everyone needed a common language—and Morse code provided it. It became the first truly global messaging format. Operators from different countries could tap out and understand each other’s messages without ever sharing a mother tongue. It was a language of pulses, unburdened by accents or alphabets.

A Foundation for the Future

Looking back, I see now that Morse code was more than just a tool for communication. It was the world’s first digital language. Each dot and dash was a binary signal—on or off, short or long, yes or no. It worked much like the ones and zeros used in modern computing. We didn’t have microchips, of course, but we had the idea: that information could be broken down into basic units and transmitted rapidly, accurately, and universally. It was, unknowingly, the foundation for all future digital systems.

The Music of Connection

There was something beautiful in the code, too. Operators could hear it like music, feel it in their fingertips. Entire conversations flowed through the ticking of a telegraph key. A skilled hand could tap out joy, sorrow, urgency, or relief with just a rhythm. It brought a kind of poetry to technology. And while it took time to learn, those who mastered it became part of a silent brotherhood—speaking through electricity, across mountains and oceans, often without ever seeing each other’s face.

What the World Understood

Today, we take instant communication for granted. But Morse code was the first time the world agreed on how to speak through machines. It was the start of a global conversation—one made possible not by noise or paper, but by pattern and pulse. I never imagined it would last into the age of radio, or be used in times of war and rescue long after I was gone. But I am proud to have given the world a common tongue in the language of sparks, and to have helped it speak more clearly across the silence.

My Name is Rowland Hill: The Man Who Reformed the Postal Service

I was born in Kidderminster, England in 1795, into a family that valued reason, discipline, and education. My father was a schoolmaster with progressive ideas, and from him I inherited both a strong sense of social responsibility and a love of structure and logic. As a young boy, I was drawn not just to books, but to the systems behind things—how they worked, how they could be improved. By the age of twenty, I was helping run a school with my father and brothers, where we taught science, mathematics, and moral philosophy. Even then, I was thinking about efficiency—not just in machines, but in the very way people lived and communicated.

The Problem with the Post

By the 1830s, I had left teaching and begun to explore public administration and reform. That’s when I turned my attention to the British postal system. It was a mess. Rates were wildly inconsistent, often calculated by distance and number of sheets. Many ordinary people simply couldn’t afford to send or receive letters. Worse, recipients—not senders—paid the postage, and many refused to accept letters because they couldn’t afford the cost. I believed communication was a public good. If we could reform the post, we could connect families, grow the economy, and foster a better-informed society.

One Penny, One Rate

In 1837, I published a pamphlet titled Post Office Reform: Its Importance and Practicability. In it, I laid out a simple idea: reduce postage to a single, affordable rate—one penny per half-ounce—regardless of distance. Make the sender pay. And, to make it even easier, create something entirely new: a prepaid adhesive label. The postage stamp. Many dismissed me as a dreamer, but I wasn’t alone. Public support for the reform swelled. In 1840, the government adopted my plan, and the first stamp—the Penny Black—was issued. It bore the image of Queen Victoria and changed the world overnight.

Facing Resistance

Though my plan succeeded, not everyone welcomed it. I was met with suspicion and bureaucratic resistance. I briefly left government service but returned in 1846 as Secretary to the Postmaster General. Over time, I oversaw further improvements: faster deliveries, clearer organization, and wider access to the mail for people across the British Isles and beyond. Under my leadership, the mail became a tool of the common person, not just the wealthy or powerful. It thrilled me to see working-class people sending letters to loved ones and businesses booming through correspondence.

Global Ripples

What began as an English reform soon inspired the world. Other nations adopted uniform postal rates and stamps. Suddenly, the world was more connected than it had ever been. Commerce, family, and governance all benefited from reliable communication. In many ways, I believe this humble piece of paper—the postage stamp—helped pave the way for the modern information age. It wasn’t just a token; it was a symbol of fairness, access, and dignity.

A Quiet Legacy

I was knighted in 1860, which was a great honor, but I remained a modest man at heart. I never sought fame, only function. I wanted systems that worked well and served people equally. I died in 1879, not long before the telephone and other marvels would emerge. But I believe my reforms laid the groundwork for them. Communication should not be a luxury—it should be a right. And I am proud that my life's work helped bring that idea closer to reality.

A Broken System: Postal Reform and the Penny Post – Told by Rowland Hill

In the early part of the 19th century, I watched with growing frustration as the British postal system faltered under its own weight. It was expensive, complicated, and deeply unfair. The cost of sending a letter depended on the number of sheets of paper and the distance it had to travel. Worse still, the person who received the letter—not the sender—was responsible for the fee. Many refused to accept letters because they couldn’t afford them, and messages were often left unread or went undelivered. To me, this wasn’t just inefficient—it was unjust. Communication is the thread that holds families, commerce, and governance together. I believed it should be within reach of every citizen, not just the wealthy.

A Radical Proposal

I was not a postman or a politician by trade. I was a schoolmaster and a man of logic. But I applied the same principles of fairness and simplicity I taught in the classroom to the problem at hand. In 1837, I wrote a pamphlet titled Post Office Reform: Its Importance and Practicability, which laid out my ideas plainly. My plan was to standardize the cost of postage to a single, low rate—one penny for any letter weighing up to half an ounce, regardless of distance. To simplify payment, I proposed a revolutionary idea: an adhesive label, prepaid and placed on the envelope. Thus, the postage stamp was born.

Facing Resistance

My proposal was met with skepticism and resistance from many corners of government and society. Critics warned it would bankrupt the postal service. Some laughed at the idea of ordinary people sending so many letters. But the public supported me, and so did members of Parliament who believed in progress and equity. After three years of debate and planning, the Penny Post was officially launched in 1840. The first stamp—the now-famous Penny Black—bore the profile of Queen Victoria and cost exactly one penny. It was the first time in history that anyone, from a wealthy merchant to a rural farmhand, could send a letter anywhere in the country for the same low price.

Communication for the People

The effect was immediate and profound. Letter writing exploded. Families separated by distance could now stay in touch regularly. Workers in the cities could write home to their parents in the countryside. Soldiers and sailors could send news without fear of placing a burden on their loved ones. Businesses thrived on the fast, affordable exchange of contracts and orders. Schools encouraged writing letters as part of literacy education. For the first time, communication became truly democratic—an everyday right, not a privileged act.

A Model for the World

Other countries quickly took notice. The principles behind my reform—uniform rates, prepaid postage, simple weight-based fees—were adopted across Europe, and eventually around the world. Nations created their own postage stamps and modernized their delivery systems, inspired by the success of the Penny Post. What began as a British innovation became a global standard. Borders did not disappear, but the distance between people began to shrink.

A Legacy of Connection

When I look back on it now, I do not see the stamp as just a square of paper. I see it as a symbol of access, fairness, and progress. It connected grandparents to grandchildren, farmers to markets, lovers across cities, and citizens to their governments. It gave a voice to people who had long been silent. My reform was never about profit—it was about principle. I believed that a nation strengthened by connection was a stronger, kinder nation. And in helping people put pen to paper without hesitation, I believe we unified hearts as much as we did lands.

My Name is Friedrich Koenig: Inventor of the High-Speed Steam Printing Press

I was born in 1774 in Eisleben, Germany—a place best known for Martin Luther, not for machines. But from a young age, I was fascinated not with theology, but with how things worked. My parents were farmers, and I was expected to follow in their path, yet my heart was drawn to the hum of presses and the scent of ink. I apprenticed at a local printer’s shop, where I first saw the ancient, hand-powered press in action. It was slow. It was laborious. And I couldn’t help but wonder—why hadn’t it changed in centuries? Why were we still printing as if Gutenberg himself were watching?

A Dream of Steam

As the Industrial Revolution took hold, steam began powering everything from looms to locomotives. I wondered, could it not also power the press? I knew such an invention could transform the speed of communication—faster books, faster newspapers, faster exchange of ideas. But turning that dream into a working machine was no easy task. I worked in secret, perfecting a design that used cylinders instead of flat plates, and steam instead of hand labor. I left Germany for London in 1804, hoping for better opportunities, but the British printing establishment was wary—afraid my machine would put workers out of jobs. Still, I pressed on.

The Machine Comes to Life

At last, I found a supporter—Thomas Bensley, a forward-thinking printer who believed in my vision. Along with engineer Andreas Bauer, I built the first successful steam-powered printing press. In 1814, our invention was secretly installed in the offices of The Times of London. One morning, without warning, the paper came out printed not by hand but by machine—1,100 sheets per hour, instead of a few hundred. The pressmen were stunned. The age of mechanical printing had arrived, and nothing would ever be the same.

Spreading the Word

The new press wasn’t just faster—it was more consistent, more efficient, and far cheaper in the long run. Soon, my machines were printing newspapers across Europe. Literacy rates were rising, and now printed material could keep up with the public’s hunger for news, knowledge, and stories. My invention helped newspapers go daily. Books became more affordable. Pamphlets, educational texts, political materials—ideas could now spread with a power and speed never seen before. It was not just a mechanical change, but a social revolution.

Returning Home

Though I found success in England, I eventually returned to Germany and founded Koenig & Bauer with my loyal partner. Together, we built more advanced machines, and our factory became a cornerstone of European printing innovation. I died in 1833, just as the power of mass communication was beginning to ripple through every part of society—from politics to education, business to art. I had not invented printing, but I had reimagined it for the modern world.

A Legacy on Every Page

Looking back, I do not measure my success in wealth or accolades. I measure it in the printed word—in the newspapers read by factory workers, the novels devoured by young minds, the scientific journals passed between scholars. I believed that faster printing could make the world smarter, more connected, and more just. If a single pressman could reach thousands with truth or imagination, then progress was not just mechanical—it was human. And that was the revolution I wanted to power.

The Rise of the Newspaper and Political Journalism – Told by Friedrich

In my younger years as a printer's apprentice in Germany, I found myself staring with disbelief at the sluggish, hand-operated presses we used—devices barely changed since Gutenberg’s time. I admired the craft, but I grew restless with its limits. Newspapers took hours, even days, to print in any quantity, which meant only the wealthy could afford to publish, and the working class remained largely uninformed. It troubled me. Ideas were being generated faster than they could be shared. What good was freedom of speech, I thought, if the very tools of communication were bottlenecked by outdated machines?

Powering the Press with Steam

After years of development, experiments, and many setbacks, I designed a press that could do what no other had: use steam power to drive a rotary cylinder, pulling paper through and printing both sides at astonishing speed. With the help of my brilliant partner, Andreas Bauer, and the brave support of Thomas Bensley in London, we installed the machine in secret at The Times newspaper. In 1814, it printed over a thousand copies per hour—an unimaginable speed at the time. When it was revealed, the world took notice. And suddenly, the rules of publishing began to change.

A New Era of Daily News

With steam at their side, newspapers were no longer luxury items printed weekly or in small batches. They became daily, affordable, and widespread. What once took a dozen men to print in an hour could now be done by one machine in minutes. This wasn’t merely a technical advancement—it was a social one. Now, printers could serve vast urban populations. Readers in Liverpool or Leipzig could hear about events in London or Paris that very morning. The public didn’t have to wait for rumor or word of mouth—they could hold the news in their hands before the ink dried.

Fueling Political Awareness

As newspapers became faster and cheaper, political journalism exploded. Editors and reporters began shaping public opinion in ways never seen before. Ideas about reform, labor rights, monarchy, and democracy filled the columns. Debates that once happened in quiet salons were now published for the streets. Political movements found allies in journalists. Ordinary people, reading the paper by candlelight, began to form opinions, write letters to editors, and even gather in protest. I saw with my own eyes how a faster press meant a faster, sharper society. We were no longer whispering ideas—we were printing them in bold.

The People's Voice in Print

Before the steam press, news belonged to the few. After it, it belonged to the many. Workers, students, shopkeepers—all could access information and join the conversation. In some countries, governments feared this power and tried to censor the presses, but the machine had already done its work. It was no longer possible to turn back the tide. Once the people had a taste for the daily paper, they would never go without it again.

A Revolution Beyond Gears

When I reflect on my invention, I know it was more than a marvel of engineering. It was a force for democracy. My steam press did not just multiply pages—it multiplied voices. It allowed for disagreement, debate, and discovery to happen faster and more widely than ever before. And while I may not have written the editorials or reported from the fields, I gave those brave writers the means to speak loudly and often. That, I believe, is the quiet power of invention: to hand others a louder pen and watch the world begin to answer back.

My Name is Elizabeth Gaskell: Rise of Mass Literacy

I was born in 1810 in London, but my earliest memories are not of the bustling city, but of the calm countryside of Knutsford in Cheshire, where I was sent to live after my mother died when I was just a baby. My father, a stern man of letters, felt unequipped to raise a child alone. In Knutsford, under the care of my aunt, I grew up surrounded by quiet gardens, provincial manners, and the rhythm of small-town life. Those years would later shape my novels, which often balanced gentility with the grit of real struggle. I watched people carefully, listened to their stories, and absorbed their pain and joys like sunlight soaking into cloth.

Marriage and Manchester

In 1832, I married William Gaskell, a Unitarian minister in Manchester. It was there that I was truly awakened—not only to the trials of the working class, but to the power of words as a means of understanding and change. Manchester was a city swollen by industry, smoky with progress, and divided by class. While my husband ministered to the poor and taught at working men's colleges, I walked among the factory streets and sat with the sick and struggling. The stories I heard did not leave me. They begged to be told. And so, I began to write.

Mary Barton and the Voice of the Working Class

When our infant son died in 1845, I turned to writing as a way to grieve and heal. The result was Mary Barton, my first novel, published anonymously in 1848. It told the story of a working-class girl caught in the web of poverty and love in industrial Manchester. It shocked many. Some accused me of being too political, too sympathetic to the poor. But others—Charles Dickens among them—saw in me a new kind of voice. I wasn’t merely telling stories. I was shining a light on the injustice that modern England often tried to ignore.

Writing for Change

Dickens invited me to write for his magazine, Household Words, and through that platform I published Cranford, North and South, and many of my best-loved stories. I tried always to blend storytelling with truth—to show not just what people did, but what they felt. In North and South, I gave voice to both factory owners and workers, exploring their conflicts with honesty and compassion. I did not write to preach, but to build bridges. Literature, I believed, should open the heart before it changed the mind.

A Woman Among Giants

As a female author in a world still hesitant to take women seriously, I found myself both celebrated and scrutinized. I counted Charlotte Brontë among my dearest friends, and after her death, I was honored—and burdened—with the task of writing her biography. It was a challenge to capture her truth while protecting her dignity, but I did what I believed was right. My own life was filled with balancing acts: wife and writer, mother and moralist, friend and reformer. Yet through it all, I kept writing.

The Power of the Printed Word

What I witnessed during my lifetime was nothing short of a revolution—not just in factories and locomotives, but in minds. Printing presses multiplied, books became cheaper, literacy spread, and women began to read and write in greater numbers. I believed communication could be a force for empathy, for justice, for human connection. That is why I told stories of the overlooked, the overworked, the misunderstood. Through characters like Margaret Hale and John Barton, I tried to let readers hear the voices they’d never listened to before.

A Life of Letters

I died in 1865, never quite believing how far my stories had reached. I was not loud or radical, but I believe I was firm and faithful to what I saw. I loved people, even in their contradictions. And I believed that if we could just speak to one another, really speak, the world might soften its sharp edges. That, after all, is the true revolution—not of machines, but of hearts made wiser by words.

Role of Women in Publishing and Communication – Told by Elizabeth Gaskell

In the early years of my life, it was often said that women should be silent in public matters and speak only in the realm of the home. But even in those narrow spaces, women read. We read in parlors, in dim kitchens, on back steps between chores. We read novels passed hand to hand, borrowed from circulating libraries, or tucked secretly beneath sewing baskets. Reading gave us more than escape—it gave us knowledge, imagination, and the confidence to ask questions. As literacy spread during the Industrial Age, it was women who often consumed the printed word most hungrily, and in doing so, prepared themselves to shape it.

Pen Names and Private Pages

When I first began to write, like many women of my time, I did so anonymously. It was safer that way. Critics were less likely to dismiss or mock if they thought the words came from a man. But even hidden behind initials or pseudonyms, we were there. Writing novels, articles, poems, and letters that carried truth and experience from the private world to the public one. Women wrote of work and hardship, of loss and loyalty, of injustice and faith. We did not yet stand at pulpits or podiums, but through the printed word, we found our stage.

Editors, Publishers, and Partners

As the century turned, more women began not only to write but to shape what others read. Some became editors of household magazines or literary journals. Others influenced their husbands’ editorial work or ran publishing ventures themselves. Even if they remained behind the curtain, their presence was felt. I was fortunate to work with Charles Dickens, a man who, while often impatient with my caution, understood the importance of women's voices in storytelling. Through publications like Household Words, I—and many other women—found a way to share what we saw in the shadowed corners of factory towns and rural homes.

Teachers and Letter-Writers

Outside the world of print, women became powerful communicators in more personal ways. As teachers, we shaped young minds. As mothers and aunts, we taught reading and writing by the hearth. As letter-writers, we kept families connected across distances that had grown vast due to migration and war. A single woman’s letter could carry comfort, guidance, or protest. Women may not have held office, but we kept the emotional infrastructure of society alive through correspondence, education, and storytelling. We passed down history and preserved relationships in ink.

Finding a Public Voice

Over time, more women began to write under their own names. Their novels tackled labor issues, child welfare, moral struggles, and even politics. Some, like Harriet Beecher Stowe in America or the Brontë sisters here in England, stirred whole nations with their prose. As printing became faster and books more affordable, our audience grew. No longer limited to the drawing rooms of the upper class, our words reached factories, farms, and schoolhouses. We were still told to mind our place—but our place now included the bookshelf, the magazine stand, and the newspaper column.

The Power of Shared Words

I always believed that storytelling could soften hearts and strengthen minds. That belief was not mine alone—it was shared by countless women who picked up the pen and spoke through fiction, essay, or memoir. During the Industrial Age, communication expanded, and so did our voices. We did not shout. We whispered, wrote, taught, and endured. And slowly, those whispers became impossible to ignore. The world began to listen—not just to what women felt, but to what we thought, believed, and dreamed.

A Legacy Still Unfolding

As I reflect on my life and the world I lived in, I see how far we came and how much further there is to go. The presses kept turning, and with each new edition, more women found the courage to speak. We were once only readers. Then we became writers. And now, we are architects of communication itself. That is the story I am proud to be part of—not just my own, but a chorus of women whose words built bridges where there were once walls.

Industrial Printing and the Democratization of Books – Told by Friedrich

In my youth, I worked among the clatter of hand-operated presses, where each page had to be inked and pressed manually. The process was beautiful, but painfully slow. A skilled printer might produce a few hundred sheets in a day. Books were precious and expensive, often locked behind glass or reserved for the wealthy. The common laborer could barely afford a newspaper, let alone a full volume of literature or science. I saw knowledge caged by mechanics, limited by muscle and time. And I believed it was time to set it free.

A Machine for the Masses

My dream was not just to speed things up—it was to break open the world of books and place it in the hands of ordinary people. With my partner Andreas Bauer, I built a steam-powered press that could print thousands of pages per hour, consistently and affordably. Instead of printing one sheet at a time, our press used rotating cylinders to pull paper through, printing both sides as it passed. What once took days could now be done in an hour. The cost of producing a book dropped dramatically. For the first time in human history, mass printing became truly possible.

Opening the Gates of Learning

With faster presses, publishers began to rethink their business. It no longer made sense to print only for the elite. They could now produce hundreds—then thousands—of copies for a growing reading public. Novels, histories, religious texts, educational primers—these could now be printed in bulk and sold cheaply. Lending libraries expanded. Bookstores filled their shelves with volumes priced for the middle class. Schools could afford more materials. Children grew up with stories in their hands. The printed word was no longer a treasure hoarded by the few—it was a tool shared by the many.

A Reader in Every Home

I saw firsthand how the spread of books changed daily life. Families read aloud in the evenings. Factory workers brought slim paperbacks on their lunch breaks. Farmers, shopkeepers, and students all gained access to ideas and inspiration. Books no longer waited for scholars in quiet studies—they lived on crowded shelves, in coat pockets, beside bedside lamps. And with every new print run, more people found a voice, a hero, or a truth that spoke to them. We were not just printing pages. We were printing possibility.

The Spread of Ideas

As books became more available, their influence multiplied. Political ideas reached distant towns. Scientific discoveries crossed borders. Literature helped people see the lives of others with empathy. A novel might soften hardened opinions. A history book could reshape a young mind. And as books traveled, they wove a web of shared knowledge, across class and continent. The steam press did not just make printing faster—it made it louder, broader, and more inclusive. The world began to think in common texts.

My Part in the Revolution

I was no great author. I did not write the words that filled those pages. But I gave those words wings. And that, to me, is enough. I built the machine, but it was society that ran with it. I believe that printing, once powered by steam, became something more than mechanical—it became democratic. No longer locked behind wealth, books belonged to everyone. And in the hum of those machines, I heard the sound of progress. I did not invent literacy, but I helped speed it forward, page by page, press by press, until no voice had to remain unread.

Communication Across Empires: Telegraph and Global Control – Told by SamuelWhen I first imagined the telegraph, my thoughts were humble—letters sent faster, news arriving in time, families no longer torn by delay. But as wires stretched farther and faster than I ever anticipated, I watched something remarkable unfold. The telegraph did not merely connect towns or nations. It connected empires. The same simple pulses I tapped out in Washington now coursed through cables under oceans, across deserts, and through jungles. It was as if a nervous system had been laid across the world, and for the first time in human history, distant powers could speak to their outposts instantly, no matter how far.

The Empire and the Wire

Nowhere was this more evident than in the British Empire. With colonies scattered across continents—from India to Africa to the Caribbean—the British faced a problem of distance. Decisions made in London could take weeks to reach Calcutta, and responses just as long to return. But once telegraph cables were laid, first across Europe, then across the Mediterranean, and finally under the sea to India, everything changed. Governors no longer acted with outdated instructions. They received orders almost in real time. Rebellions, trade disputes, treaties—London could respond within hours rather than months. The empire gained a kind of speed it had never known before.

Trade at the Speed of Signal

Beyond politics and war, commerce felt the transformation just as powerfully. Merchants and investors no longer waited for ships to carry market reports. A change in cotton prices in Bombay could be known in Manchester that same day. The telegraph allowed businesses to adjust their shipping schedules, move goods more efficiently, and trade in ways that demanded precision. Banking, insurance, and global stock exchanges flourished under the certainty of fast information. Entire economies began to operate at the pace of the telegraph’s tick.

The Telegraph as a Tool of Control

But this power was not evenly shared. The same cables that brought connection also reinforced control. Colonies that once operated with a degree of local autonomy found themselves tethered tightly to imperial headquarters. Local governors had to answer quickly, armies moved under instruction from afar, and native voices were often drowned beneath foreign orders that arrived at lightning speed. I had hoped the telegraph would bring people together in understanding, but I could not ignore that it also made domination more efficient. Technology, I learned, has no morality of its own—it serves the hand that holds it.

A New World Order in Code

As other empires—French, Russian, Ottoman—saw what Britain achieved through wires, they followed suit. Telegraph stations became critical outposts, as important as forts or ports. Submarine cables turned oceans from barriers into corridors of command. The world began to shrink—not in size, but in delay. With this compression came a new kind of empire: one ruled not only by force or flag, but by information. And at the center of it all, the quiet, steady rhythm of Morse code.

What the Wires Whispered

In the final years of my life, I stood in wonder at what we had made. The telegraph did not just alter communication—it reshaped diplomacy, warfare, trade, and authority. It made the globe feel smaller, but also more complex. I had once sent a message from Washington to Baltimore and marveled at the speed. Now, governments sent messages from London to Singapore and expected replies before the sun rose again. This was no longer science fiction. This was reality. The world had become wired, and with every pulse that raced along those cables, the age of empires found a new rhythm—measured not in months, but in moments.

Letter Writing as a Social Art and Lifeline – Told by Elizabeth

It was on a rainy afternoon in London, at a quiet gathering hosted by a mutual friend, that I, Elizabeth Gaskell, first had the pleasure of speaking at length with Sir Rowland Hill. Though I had admired his reforms from afar, I had never expected the man who had reinvented the post to be so soft-spoken and thoughtful. We sat near the fire, teacups in hand, and naturally, our conversation turned to the subject of letters—their meaning, their magic, and their place in a world now spinning faster than ever.

The Power of the Personal

“Mrs. Gaskell,” Rowland began, “when I proposed the Penny Post, many thought it a matter of mathematics. But to me, it was always about people. Letters are lifelines. A farmhand writing home, a soldier’s message to his mother, a child’s scribbled greeting—these are no less vital than any parliamentary report.” I smiled and agreed. “Indeed, Sir Rowland. I have seen women in Manchester clutching letters as if they were treasures. Their husbands away at war, their sons off at sea, and the only thread between them is ink on paper.” We both understood that a letter could contain far more than words. It held breath, presence, hope.

Letters of Love and Longing

Courtship by letter, I told him, had always fascinated me. Before the telephone, before the telegram, young men and women sent their hearts folded in envelopes. Their feelings matured slowly, wrapped in careful phrases and elegant penmanship. “It was a dance of patience,” I said. “One waited weeks for a reply, yet the anticipation made the love deeper, perhaps more poetic.” Rowland chuckled. “And now that we’ve shortened that waiting with affordable postage, we’ve changed the tempo of romance forever. But the letter still remains, does it not? Even in speed, there is charm.”

The Soldier’s Ink-Stained Voice

Rowland’s face grew more solemn when I mentioned war. “During the Crimean campaign,” he said, “we received countless accounts of the importance of letters to morale. Men in trenches waited desperately for news from home. It was often the only connection they had to peace, to purpose.” I recalled scenes I had heard and written about—wives reading aloud to children, fathers passing around the only page they’d received in months. “And the letters going the other way,” I said, “they were lifeboats for those left behind. A single line from the front could calm a household or shake it.”

Business by Post and the Pulse of Commerce

“Not every letter stirs the heart,” Rowland said, with a small smile. “But even those that merely confirm a shipment or settle a debt carry a different kind of weight. Commerce, like affection, depends on trust—and trust needs communication.” His system had allowed merchants to negotiate from afar, employers to hire through correspondence, and newspapers to grow through subscriptions delivered by post. “It turned ink into industry,” he added. “And yet, it remained intensely human.” I agreed. “Even in business, the tone of a letter reveals much. Character can live between the lines.”

The Family Thread

We both paused when the conversation turned to family letters. “The first time I sent my daughter away for schooling,” I said softly, “it was the arrival of her letters that kept me from mourning too deeply. Her words were like her voice in the room again.” Rowland nodded. “And imagine how many thousands feel the same, thanks to a penny stamp. Parents writing to children, siblings keeping in touch across towns, emigrants sending updates from foreign lands. The post has become a map of the heart.”

A Lasting Legacy

As the fire burned low and guests began to leave, I turned to Rowland with gratitude. “You gave us more than a stamp. You gave us back our words, our relationships, our stories.” He looked down, humbly. “And you, Mrs. Gaskell, gave those words their rightful beauty. I merely carried them.” We parted with a handshake and a shared understanding—that in a world of steam and wires, the handwritten letter still held a place of quiet power. It was not just paper. It was presence. And in every folded page was the shape of a life reaching out to be remembered.

Communication and Social Reform Movements – Told by ElizabethI came of age in a time when the printed word was growing louder, faster, and more urgent. The Industrial Age had given us machines, but it also gave us questions—about justice, humanity, and the future we were building. In the smoky cities and quiet towns of England, a new force was rising—not one of arms, but of ideas. It began in pamphlets passed hand to hand, in letters read aloud by candlelight, and in serialized stories tucked into family journals. Communication became a vessel for reform. And in this rising tide, I found my place—not as a politician, but as a storyteller who could carry truth into parlors and into hearts.

Abolition and the Call for Humanity

Among the most powerful movements I witnessed was the cry for the end of slavery. Though Britain had outlawed the slave trade in 1807 and slavery itself in 1833, its legacy lingered. The suffering of Black men and women in the colonies was still too often hidden from view. But stories—true stories, raw stories—began to emerge. Abolitionist tracts, slave narratives, and fierce essays crossed oceans, landing in the hands of readers hungry to understand. Frederick Douglass came to speak in Britain, and his words echoed in churches and lecture halls. I remember hearing his voice and feeling the power of a life shaped by injustice—and the courage it took to tell it. Communication gave the movement its heartbeat. With every newspaper article, letter, and book, the world grew less willing to look away.

The Working Class Finds Its Voice

In Manchester, where I lived much of my life, I saw the struggles of the working poor daily. Children blackened with soot. Mothers with empty pantries. Men bent under the weight of factory discipline. For too long, their pain was invisible to those in power. But the press began to change that. Reformers published essays in working-class newspapers, arguing for labor rights, education, and fair wages. I did my part through fiction. In Mary Barton and North and South, I gave faces and names to the invisible—tried to help my readers see that beneath the grime and weariness were souls as worthy as any aristocrat’s. I received letters from readers—some angry, some grateful—but all engaged. And that, I believed, was progress.

The Long Road Toward Women's Suffrage

The question of women’s place in society lingered like smoke after a fire. We were readers, writers, mothers, and workers, yet still treated as second-class citizens in law and public life. The movement for women’s rights, especially the vote, was just beginning to stir in my lifetime. But already, it had found its wings through print. Women like Harriet Martineau and others used their pens to challenge assumptions. Magazines and journals offered space for women to speak to each other and to the world. I did not march or organize rallies, but I tried to show, through characters and quiet moments, the dignity of a woman’s inner world—her intelligence, her resilience, her need to be heard. Words paved the road before the votes arrived.

Stories That Stoked the Fire

Communication didn’t always come through manifestos or speeches. Sometimes it came through stories. A novel could do what a sermon could not—it could soften the hard-hearted and stir the indifferent. I saw this in readers’ responses to Ruth, my novel about a fallen woman. Some were outraged, yes, but others wrote to thank me for telling a story of mercy. Fiction opened doors for conversation. It allowed people to sit with difficult truths, not as abstract ideas, but as living human realities. And every printed page, every bound volume passed hand to hand, added another spark to the slow-burning fire of reform.

The Printed Word as a Mirror and Lantern

I came to believe that the printed word was both a mirror and a lantern. It showed us who we were—and who we could become. Whether a poem against child labor, a pamphlet on prison reform, or a serialized tale of an impoverished family, communication helped turn private sorrows into public causes. It connected people who had never met, gave courage to those afraid to speak, and reminded the comfortable that silence is its own kind of cruelty.

My Quiet Part in a Loud Chorus

I never shouted from a stage. I did not lead rallies or write laws. But I told the stories I had seen, and I trusted them to do their work. I believed that if I could help one reader feel empathy where before there was judgment, then I had done something worthwhile. Social reform is not just made by policy—it is made by changed hearts. And those hearts, I found, are often opened by a letter, a line, a paragraph that speaks when no one else will. In a time of machines and progress, I chose to believe that human connection—through words—was the most powerful invention of all.

Labor Exploitation in Print Shops and Telegraph Offices – Told by Samuel and Rowland

It was a quiet evening in London when I, Samuel Morse, found myself seated beside Sir Rowland Hill at a private gathering of reformers and inventors. The conversation drifted from the marvels of our work—the speed of the telegraph, the reach of the penny post—to the cost that came with it. We had both helped revolutionize communication, but we couldn’t help reflecting on those whose hands kept our machines and systems running. As the tea cooled on the table before us, we spoke not of cables or codes, but of the people whose lives played out in the shadow of our inventions.

Children Among the Presses

“I have walked through the print shops of Fleet Street,” Rowland began, “and while I marvel at the precision of the steam presses, I cannot ignore the sight of young boys wiping rollers, hauling reams of paper, their faces smudged with ink and exhaustion. Some no older than ten.” I nodded slowly. “In New York, it is the same. The printing press demands speed, and speed demands bodies—cheap, tireless, and small enough to fit between machines. Children work twelve-hour days, sometimes longer, barely stopping to eat.” He sighed. “We made communication faster, but we did not think enough about those who now bear its weight.”

Operators in the Shadows

“The telegraph office,” I added, “has become a place of quiet endurance. The operators—mostly young men, but also women, especially in rural areas—sit hunched over keys and wires for hours, their ears tuned to the ticking language of dots and dashes. There’s great skill in it, but little recognition. They are expected to be fast, accurate, always alert. One mistake could send the wrong message to a general, a banker, a grieving family.” Rowland leaned forward. “And the women?” I looked at him. “They are often paid half the wage of the men, despite doing the same work. Some are praised for their delicacy with the key—quick, nimble fingers—but not respected as equals.”

The Price of Progress

“We thought we were bringing knowledge to the people,” Rowland said, almost to himself. “And we did. But perhaps we underestimated how industry consumes effort without always returning dignity.” I agreed. “Progress has two faces. One speaks to the public, promising a better tomorrow. The other whispers behind closed doors, where laborers sweat and strain to meet the speed we set.” He tilted his head thoughtfully. “We celebrated how the post brought families closer, how the telegraph shortened distances. But what of the children who never read the papers they print? What of the girls who tap messages they’ll never be able to afford to send?”

A Hope for Reform

“We cannot undo the machines,” I said. “But we can speak, as men of influence, about how they are used. We can advocate for education, fair wages, protection for workers.” Rowland straightened. “Yes. Communication must not be built on silence. If we give voice to the exploited, if we help ensure their labor earns respect, then our inventions may yet serve their highest purpose.” I looked at the flickering lamplight and imagined a world where the hum of progress did not drown out the whisper of justice.

The Unseen Hands

That night, as we parted, we did so not just as inventors, but as men burdened with a new responsibility. The telegraph and the postal system had transformed the world. But the world, in turn, had revealed its fragile seams. Beneath every stamp and wire were hands—young, weary, and often unheard. And if our work was to mean anything lasting, it must eventually lift not just the minds of nations, but the lives of those who made it all possible.

Censorship and Government Control of Information – Told by Friedrich and Elizabeth

It was late in the day when I, Friedrich Koenig, found myself in conversation with Mrs. Elizabeth Gaskell during a visit to Manchester. She had come to see one of the newer presses I’d helped design—machines now churning out books and newspapers by the thousands. As we stood near the great iron frame, its gears silent for the moment, we fell into a conversation not just about the power of the printed word, but about the troubling ways that power could be manipulated. Elizabeth, always thoughtful, raised a point that hung heavily in the air.

The Watchful Eyes Behind the Curtain

“You know, Mr. Koenig,” she began gently, “as much as I value the written word, I worry about who decides what may be read. I’ve heard from friends in Ireland and abroad that letters are often opened by authorities—intercepted and scrutinized before they ever reach their intended hands.” I nodded solemnly. “Indeed, madam. In Germany, and elsewhere, governments have come to fear the very machines they once embraced. They approve newspapers one day, and shutter them the next if the ink turns against their interest. In Prussia, I once saw a journal confiscated for printing a student’s harmless essay—too bold for the Minister’s liking, apparently.”

The Empire’s Grip on the Wire and the Mail

Elizabeth’s brow furrowed. “It is the same with the post,” she said. “Sir Rowland Hill’s reform made letters affordable, yes—but also easier to monitor. I have heard whispers that during times of unrest, especially in the colonies, the British government seizes mail without warrant, searching for signs of dissent or rebellion.” I nodded again, deeply troubled. “And with the telegraph, it is no different. Messages travel faster, but they pass through central stations—many of them watched by state-appointed clerks. Cables meant for love or truth are often interrupted by silence or punishment. In France, entire regions have seen the telegraph wires used only to carry orders, never questions.”

Controlling the Conversation

Elizabeth sighed, her voice quiet. “What frightens me is how quickly we have begun to accept this—how easily people believe only what is printed, without asking who approved its printing.” I replied, “And how some governments use presses not to inform, but to flood the people with what they want them to believe. During uprisings, I’ve seen pamphlets spread like wildfire—some real, some false, most printed under orders. When information moves fast, it becomes a tool of command as much as connection.” She shook her head. “Even fiction is not safe. When Mary Barton was first released, I was accused of fanning flames, simply for portraying the lives of the poor with honesty.”

Hope Between the Lines

“But surely,” I offered, “the very act of printing gives us a chance to resist. A banned article today may return tomorrow under a new name. A censored letter may be rewritten in metaphor. The truth has a way of slipping through.” Elizabeth nodded. “Yes, and stories, even if not political on their surface, can carry truth quietly. A character’s sorrow may mirror the injustice of a nation. A family’s letter may carry more than affection—it may carry warning or courage.”

A Duty to Protect the Word

As the press hummed back to life, we stood in silence for a moment, watching the pages emerge—clean, sharp, and full of potential. “It is our task,” she said softly, “to ensure that communication does not become a weapon of control, but a tool of empathy.” I agreed. “And it falls to both the printer and the writer to guard against silence—not the kind born of peace, but the kind imposed by fear.”

What the Machines Cannot Silence

As we parted, I looked once more at the press, now rolling with rhythm and purpose. The machines we built had given voice to millions. But they could not decide what was spoken—that responsibility remained with us. And if we hoped to keep that power in the hands of the people, we would have to speak boldly, write carefully, and always remember that the cost of silence is often greater than the cost of speech.

Colonialism and the Telecommunication Infrastructure – Told by Samuel

When I first sent a pulse of electricity through a wire and watched it form a message—simple, immediate, unmistakable—I saw a tool of progress. The telegraph, I believed, would knit together distant families, bring nations into peaceful dialogue, and deliver knowledge where ignorance once stood. Yet even as I marveled at what we had made, I could not help but watch, with growing unease, how others used it not only to connect, but to control.

The Empire’s New Artery

It was the British who moved most swiftly. Once convinced of the telegraph’s power, they laid wire not just across their own countryside, but across continents. From London to Calcutta, from Cairo to Cape Town, the empire planted poles and buried cables—lines of communication that looked, on the surface, like modern marvels. But beneath them, deeper than the wires, ran currents of authority. These were not merely tools for talking—they became chains of command. Governors in the colonies no longer had space for reflection or negotiation. Orders came fast, firm, and final from the imperial center.

Wires Laid by the Weary

What disturbed me further were the conditions under which these networks were built. In the heat of Africa, under the canopy of Southeast Asia, and across the deserts of Australia, local populations were conscripted—sometimes hired, sometimes forced—to dig trenches, clear forests, and string cable across unforgiving landscapes. Many labored under brutal supervision. Some died under the weight of imperial ambition. The telegraph may have been mine in concept, but the lines were built on backs not my own, and the burden was heavy.

The Cable Beneath the Sea

One of the greatest feats of engineering in my lifetime was the laying of the transoceanic cables. When the first successful message crossed the Atlantic, the world celebrated. But few noticed the silent spread of similar cables stretching from Britain to its colonies. The All Red Line, they called it—a web of telegraph cables connecting the empire in real time. These cables turned the oceans from barriers into fast lanes of command. Uprisings could be reported instantly. Naval fleets could be redirected in hours. The colonies, once allowed moments of delay and autonomy, now lived in the constant shadow of surveillance.

A Voice That Could Not Speak Back

The irony that pained me most was this: the very technology meant to give voice to the world often silenced those on the far end of the wire. The colonized were not sending messages across the oceans—they were receiving them. Edicts, policies, demands. Their responses, if they were permitted at all, were filtered through British agents or suppressed entirely. The telegraph had the potential to be a bridge between peoples, but in practice it too often became a whip disguised as wire.

Reflections on My Invention’s Reach

I do not regret creating the telegraph. I still believe it is one of the great instruments of human progress. But I have come to understand that no invention exists in isolation. The telegraph did not arrive in a vacuum. It was seized by empires, woven into strategies of expansion, and made to serve ambitions far different from my own. I wanted to unite hearts. Others wanted to tighten reins. And in the clash between ideal and reality, it was the silent laborer, the colonized subject, and the unheard voice who bore the cost.

A Caution in Every Current

As wires continued to circle the globe, I often wondered: can any tool remain pure when placed in human hands? Perhaps not. But we must remember, as inventors, leaders, and citizens, that speed is not justice, and power is not peace. The telegraph changed the world—but it did not change human nature. That work, I think, still lies ahead.

Media Bias and the Rise of Propaganda – Told by Friedrich and Elizabeth

The printing press had finished its daily run when Elizabeth Gaskell arrived at the workshop. I, Friedrich Koenig, had invited her to see how quickly stories could now reach the public thanks to my steam-powered press. The floor still smelled of ink and oil, and sheets of newsprint lay scattered like fallen leaves. As we walked among the machines, their clatter replaced by quiet hums, our discussion turned not to the power of print—but to its growing dangers.

Speed Without Restraint

“These machines,” Elizabeth said softly, running her fingers along a freshly printed newspaper, “have given voice to so many. But I fear they have also given too much voice to too few.” I knew exactly what she meant. “When a single publisher can print tens of thousands of papers in a morning,” I replied, “they do not just report the news—they create it.” The ability to produce and circulate papers with such speed had outpaced society’s ability to question what it read. The press, meant to inform, now too often persuaded with bold headlines and half-truths.

The Influence Behind the Ink

Elizabeth shared how some reformers she knew had been smeared in the pages of city dailies. “A man calling for better wages is called a radical. A woman speaking for the vote is painted as hysterical. And yet these papers sell more with each attack.” I nodded grimly. “In Berlin, in Vienna, in Paris—there are editors who serve not the truth but their patrons. Political parties, industrial tycoons, and even monarchs slip coin beneath the table in exchange for favorable headlines.” What had once been a tool of public education had, in many cases, become a mouthpiece for power.

Sensationalism Over Substance

“It is not just who pays for the story,” Elizabeth continued, “but how the story is told. Every accident becomes a scandal. Every disagreement becomes war. It is easier to sell fear than fact.” I agreed. “Sensationalism has become its own industry. The presses that once printed philosophy now churn out gossip. A single dramatic headline can sway an election, ignite a riot, or ruin a man’s name before he speaks in his own defense.” The faster we printed, the less time readers had to reflect—and reflection, we both knew, was the heart of wisdom.

The Public's Shifting Appetite

We paused by the press as its gears cooled. “And the public?” I asked. “Do they not bear some responsibility?” Elizabeth was quiet for a moment. “They do—but how can they know better if all they are given is noise? There are still honest papers, yes, but they are drowned in shouting. The line between reporting and entertainment is blurred. People crave distraction more than truth.” It saddened us both. The same press that once printed Dickens and Darwin now favored rumors and political cartoons designed to provoke rather than enlighten.

A Shared Duty to Speak Carefully

“Invention,” I said, “is not the final step. The machine is neutral—it is the hand behind it that determines its purpose.” Elizabeth looked at me and said, “And so it is with writing. Every word carries weight. We must teach readers to ask who is speaking, and why.” It became clear to us that the future of communication depended not just on those who built the presses or wrote the words, but on those who read them. The public must become more discerning—or risk becoming puppets to those who write for profit, not principle.

The Page as a Battlefield

As we parted ways that evening, the sun slipping behind Manchester’s smoky rooftops, we both felt the heaviness of our era. We had helped give rise to voices across the globe—but also to echoes that deceived. Propaganda now rode on the back of invention. Bias wore the cloak of truth. Yet, we were not without hope. “The answer,” Elizabeth said before stepping into the street, “is not to silence the press—but to strengthen the mind that reads it.” I nodded, believing she was right. The power of the page had grown—but so must the wisdom of those who turned it.

Commentaires