Chapter 28 – Your AI Portfolio and Capstone Project

- Zack Edwards

- Dec 20, 2025

- 24 min read

Defining Your AI Identity and Career Narrative – Told by Zack Edwards

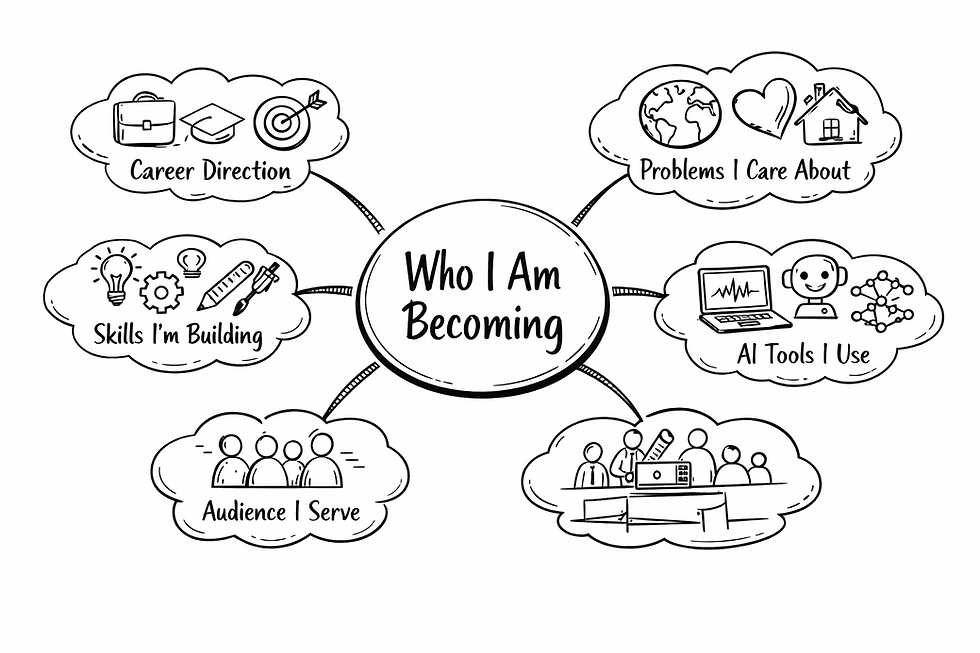

Before you choose platforms, prompts, or projects, you must decide who you are becoming. AI is not a career on its own; it is an amplifier. Without direction, it turns portfolios into scattered proof of activity instead of evidence of purpose. I have watched students create impressive work that says nothing about their future because they never paused to define their role in the world. Identity gives AI direction, and direction gives your work meaning.

Choosing a Future Self, Not a Job Title

This is not about predicting the perfect career. It is about selecting a narrative thread you are willing to grow into. Entrepreneur, designer, analyst, educator, marketer, engineer—each of these identities asks different questions of AI. When you choose who you are becoming, you also choose what problems you care about solving. Your portfolio should feel like early chapters of that story, not disconnected experiments.

Your Portfolio as a Story, Not a Storage Folder

A strong AI portfolio reads like a journey. Each project should answer a silent question from the viewer: why does this person keep making work like this? When projects connect to a central theme, they begin to reinforce one another. Random excellence is forgettable. Consistent purpose is memorable. The goal is not to show everything you can do, but to show why you do what you do.

Aligning Projects With a Mission Statement

A mission statement does not need to sound corporate or grand. It needs to be honest and clear. It can be as simple as helping people understand complex ideas, building systems that save time, or designing tools that make learning accessible. Once defined, every project should either advance that mission or challenge it in a meaningful way. If it does neither, it does not belong in the portfolio.

Building a Personal Brand Without Pretending

Personal brand is not a logo or color palette. It is the pattern people recognize in your thinking. AI makes it easy to imitate styles, voices, and aesthetics, which makes authenticity more valuable, not less. Your brand forms when you make consistent choices about tone, ethics, depth, and intent. AI should help you express that more clearly, not hide it.

Letting Identity Guide Growth

Your AI identity is not permanent. It will evolve as your skills deepen and your interests sharpen. That evolution should be visible in your portfolio. Early work may explore broadly, later work narrows and strengthens. This progression signals maturity. It tells colleges, employers, and collaborators that you are not collecting tools, but building a trajectory.

My Name is Benjamin Franklin: Printer, Inventor, Publisher, and Practical Thinker

I was not born into wealth, privilege, or inherited titles, but into curiosity, discipline, and the belief that ideas are only valuable when they can be used. Everything I accomplished came from applying knowledge to real problems, presenting it clearly to others, and ensuring that good ideas could sustain themselves through usefulness and profit.

Learning by Doing, Not Waiting

I left formal schooling early, yet I never stopped learning. As an apprentice printer, I discovered that knowledge trapped in books helps no one unless it is shared. Printing taught me discipline, accuracy, deadlines, and the importance of audience. Each pamphlet, almanac, or essay was a test of whether my ideas could survive public scrutiny. If people did not read, understand, or care, the work failed. This mindset shaped everything I later built.

Practical Application as a Way of Life

My experiments were never conducted for vanity. When I studied electricity, it was not to impress scholars but to prevent houses from burning. The lightning rod exists because theory alone is insufficient. If an idea cannot improve safety, efficiency, or daily life, it is unfinished. I believed strongly that intelligence without application is indulgence. Every invention I pursued answered a question people were already asking.

Monetization Without Shame

I never believed earning money from useful work was immoral. On the contrary, monetization ensured sustainability. My printing business funded my experiments. Poor Richard’s Almanack was profitable because it provided value people returned to year after year. Profit was not the goal; it was the proof that the work mattered. If people paid for it, they found it useful. If they did not, I improved it.

Public Presentation and Persuasion

I learned early that the best idea dies in silence if it is not communicated well. Writing clearly, speaking plainly, and appealing to common sense allowed me to persuade across class and education. I avoided arrogance and invited readers into the conversation. Whether presenting scientific findings or political arguments, I treated communication as a craft equal to invention itself.

Ethics, Responsibility, and Public Good

I refused to patent many of my inventions because I believed society benefited more from shared progress than personal monopoly. This was not self-denial but strategy. Trust builds influence, and influence multiplies impact. Innovation carries responsibility, and the public must be able to understand and trust what is being introduced into their lives.

A Portfolio of Usefulness

If you were to examine my life as a portfolio, you would not see a single masterpiece but a collection of applied works, experiments, publications, and civic projects. Each built upon the last. Each was tested by real people in real conditions. That is the measure of success I leave behind: ideas that lived beyond me because they served others.

Portfolio Architecture and Visual Design – Told by Benjamin Franklin

When a stranger encounters your work, they do not arrive with patience. They arrive with judgment already forming. I learned this early as a printer and publisher. A pamphlet unread is no better than one never written. Your portfolio must speak before you do, and it must do so quickly. In the first moments, the reader decides whether you are worth further attention, so structure is not decoration—it is survival.

Order Is a Form of Respect

I always believed that clarity is an act of courtesy. A portfolio should guide the reader without effort. Sections must appear where one expects them. Headings should announce purpose plainly. If a viewer must hunt for meaning, they will abandon the search. Good architecture allows the mind to focus on ideas rather than navigation.

Design Serves the Message, Not Vanity

Excess ornamentation weakens trust. In my own publications, I favored balance, white space, and readable type because they allowed ideas to travel unhindered. Visual design exists to remove friction. Every color, image, and layout choice must answer one question: does this help the reader understand faster? If not, it is indulgence.

The Sixty-Second Reader

I assumed most readers would skim before committing. You should do the same. A portfolio must be scannable. Clear titles, brief summaries, and visible outcomes allow someone to grasp your value in under a minute. Those who find relevance will then slow down. You must earn their time before you are granted it.

Navigation Is Silent Persuasion

When movement through a portfolio feels effortless, confidence is communicated without words. Logical flow suggests disciplined thinking. Inconsistent layout suggests confusion. I learned that how something is presented often persuades more effectively than what is said. Navigation is argument made invisible.

Accessibility Is Part of Credibility

If your work cannot be understood or accessed by a broad audience, its usefulness shrinks. I always wrote for common readers, not elites. Clear language, readable text, and inclusive design expand reach. A portfolio that excludes by accident damages trust by design.

Leave the Reader Wanting More

A portfolio is not an autobiography. It is an invitation. Give enough structure and clarity to prove competence, but allow curiosity to do the rest. When architecture and visual design are done well, the reader closes the portfolio with one thought lingering: I would like to hear more from this person.

Portfolio Architecture and Visual Design

When students begin building a portfolio, the instinct is often to start with colors, fonts, and images. I always encourage the opposite. Architecture comes first. Before opening any platform, you should know what sections you need, what story they tell in order, and what you want a viewer to understand within the first minute. A strong structure makes every design decision easier later.

Choosing the Right Platform for the Right Story

Different tools support different kinds of thinkers. Notion excels at showing process, systems, and layered thinking. It is ideal for portfolios that emphasize documentation, iteration, and long-term projects. Google Sites works best when clarity and simplicity matter most, especially for public-facing portfolios meant to be shared widely. Canva shines when visual storytelling, branding, and presentation are central. The platform should reinforce your narrative, not fight it.

Designing for Flow, Not Features

A portfolio should move the reader smoothly from one idea to the next. I advise students to imagine guiding someone through their work in person. What would you show first? What context would you give? What would you save for later? Good navigation mirrors that conversation. Clear menus, consistent layouts, and predictable section placement reduce cognitive load and increase trust.

Thinking Like a Viewer, Not a Creator

One of the hardest shifts is designing for someone who does not know you. You understand your work deeply; your viewer does not. Section titles should explain themselves. Short summaries should appear before long explanations. Visual hierarchy matters because most people skim before they read. If your key ideas are buried, they may never be found.

Balancing Personality and Professionalism

Your portfolio should feel human, but it should not feel chaotic. Personality comes through tone, examples, and choices, not clutter. Consistent spacing, readable text, and restrained color use signal seriousness. This balance tells the viewer that you are creative and reliable at the same time.

Making the Portfolio Easy to Update

A portfolio is not a finished object. It is a living system. I encourage students to build with growth in mind. Leave room for new projects. Use templates or repeating layouts. When architecture is sound, adding new work does not require redesigning everything. This habit mirrors how professionals actually work over time.

Design as Silent Communication

Long before anyone reads your words, your portfolio is already speaking. It communicates how you think, how you organize information, and how much you respect the viewer’s time. When architecture and visual design work together, your portfolio becomes more than a container for projects. It becomes evidence of clear thinking.

Showcasing AI-Assisted Writing and Research

When students first use ChatGPT, the temptation is to treat it like a shortcut to a finished product. That mindset weakens both learning and credibility. AI-assisted writing should look less like magic and more like collaboration. The goal is not to hide the tool, but to show how it strengthened thinking, clarity, and structure while leaving judgment firmly in human hands.

Choosing Work That Deserves to Be Shown

Not every AI-assisted piece belongs in a portfolio. The work you showcase should solve a real problem or communicate something meaningful: an essay that clarifies a complex issue, a lesson plan that improves learning, a proposal that persuades, or a historical narrative that brings the past to life. Strong portfolio pieces answer the question, why did this need to exist?

Documenting the Conversation With AI

What separates ethical collaboration from shortcutting is documentation. I encourage students to show how prompts evolved, how responses were evaluated, and where the AI fell short. This does not require revealing every word exchanged, but it does require transparency. Brief notes explaining why certain suggestions were accepted, revised, or rejected demonstrate control rather than dependence.

Highlighting Human Decision-Making

AI can generate options, but it cannot choose purpose. In every showcased piece, students should clearly point to moments where human judgment mattered most. This might include reorganizing arguments, correcting inaccuracies, adjusting tone for a specific audience, or adding original insight drawn from experience. These moments are the proof that the work is authored, not automated.

Revision as Evidence of Skill

First drafts are rarely impressive. What matters is refinement. Showing before-and-after excerpts or explaining how feedback, both human and AI-generated, shaped the final version reveals maturity. Revision signals ownership. It shows that AI accelerated improvement without replacing effort.

Maintaining Voice and Integrity

One of the easiest mistakes to spot is writing that sounds polished but hollow. A strong portfolio piece still sounds like the person who made it. I tell students to read their work aloud. If it feels foreign, it likely is. AI should help sharpen voice, not overwrite it.

Framing AI Use as a Strength

Used well, AI-assisted writing demonstrates modern literacy. By clearly explaining how the tool was used responsibly, students show adaptability, ethical awareness, and process discipline. These qualities matter more than flawless prose. Employers and educators are not looking for perfection; they are looking for thinkers who can work well with powerful tools.

When AI-assisted writing is presented with honesty and intention, it becomes more than content. It becomes evidence of how a student thinks, learns, and collaborates—skills that endure long after the tools change.

Visual Creation and Image-Based Projects

Visual work is often judged faster than any other medium. Before a word is read, an image has already communicated mood, clarity, and intent. When students include AI-generated visuals in a portfolio, they are not just showing what looks good—they are showing how they think visually. Images should represent ideas, not decoration, and every visual choice should have a reason behind it.

Prompt Engineering Is Visual Thinking

Tools like DALL·E reward specificity. A vague prompt produces a vague image. A thoughtful prompt reveals intention. I teach students to think of prompts as design briefs. Subject, setting, style, lighting, perspective, and emotion all matter. Writing strong prompts is not about knowing secret words; it is about knowing what you want the image to communicate before it exists.

Iteration Is Where Skill Appears

The first image is rarely the best one. Strong visual projects show refinement over time. Small adjustments to prompts—changing composition, removing distractions, altering tone—demonstrate control. I encourage students to save and reflect on earlier versions, not hide them. Iteration shows growth, and growth is more impressive than instant perfection.

Explaining Visual Intent

An image without explanation leaves interpretation entirely to the viewer. In a portfolio, that is a missed opportunity. Students should briefly explain why an image was created, who it is for, and what problem it solves. In marketing, this might be capturing attention or conveying trust. In education, it might be simplifying a complex idea. In product design, it might be testing form or function. Intent turns images into evidence of thinking.

Using Visuals to Support a Narrative

Images should connect to the broader story of the portfolio. Random styles or disconnected visuals weaken identity. Consistent themes, color choices, or illustrative approaches help reinforce personal brand. Visual work should feel like part of the same voice that appears in writing and projects, not a separate experiment.

Ethical and Responsible Use of AI Imagery

AI-generated visuals require honesty. Students should clearly note that AI tools were used and explain their role in directing the output. This transparency builds trust and avoids confusion about authorship. The value lies not in claiming to have drawn the image by hand, but in demonstrating the ability to guide powerful tools responsibly.

From Image to Impact

When visual projects are chosen carefully, refined intentionally, and explained clearly, they become more than art. They become proof of communication skill. Whether the goal is persuasion, instruction, or exploration, AI-generated visuals belong in a portfolio when they show purpose, process, and understanding.

That is what transforms images from eye-catching artifacts into meaningful work.

Audio, Video, and Multimedia Production

When ideas move, they reach people differently. Audio and video add timing, emotion, and emphasis in ways text alone cannot. In a portfolio, multimedia projects signal that a student understands modern communication. They show not just what someone knows, but how well they can explain, persuade, and guide an audience through an idea from beginning to end.

Choosing the Right Medium for the Message

Not every idea needs video, and not every explanation benefits from narration. The first decision is always purpose. Explainer videos work best when clarity is the goal. Narrated lessons serve teaching and training. Ads focus on emotion and brevity. Documentaries emphasize depth and storytelling. Students should choose formats intentionally so the medium strengthens the message rather than distracting from it.

Using AI Tools as a Production Team

Tools like Runway ML, ElevenLabs, and Hedra allow students to think like directors instead of technicians. AI handles the heavy lifting of editing, voice generation, or animation while the student focuses on structure, pacing, and clarity. The value lies in decision-making, not button-clicking.

Voice as Part of Identity

Narration is not just sound; it is personality. Whether students use their own voice or AI-assisted narration, they must consider tone, speed, and emotion. A calm instructional voice communicates trust. A dynamic voice captures attention. I encourage students to test multiple versions and choose the one that best fits the audience. This choice reflects communication awareness, not technical skill.

Visual Flow and Story Structure

Good multimedia work follows a clear arc. An opening that sets context, a middle that delivers substance, and an ending that reinforces meaning. AI can generate visuals and transitions, but structure must come from the creator. I tell students to outline their story before opening any tool. When structure is strong, production becomes refinement instead of rescue.

Polish Signals Professionalism

Clean cuts, balanced audio, readable text overlays, and consistent pacing matter. These details signal care. A portfolio artifact does not need to be cinematic, but it should feel finished. Students learn that polishing work is not about perfection; it is about respecting the viewer’s time and attention.

Explaining the Process Behind the Product

As with all AI-assisted work, transparency matters. Students should briefly explain what tools were used and why. This framing shifts attention from novelty to intention. It shows that AI was used strategically to support communication goals, not to replace effort or creativity.

When audio, video, and multimedia projects are presented thoughtfully, they demonstrate a powerful combination of storytelling, technical awareness, and audience understanding. In a portfolio, that combination speaks clearly: this student knows how to make ideas move.

My Name is Buckminster Fuller: Designer, Systems Thinker, and Solver of Global Problems

I did not set out to become famous, wealthy, or celebrated. I set out to answer one question that haunted my life: what can one individual do to improve the chances of humanity’s survival? Every project I undertook was a capstone, not because it concluded my learning, but because it demanded that everything I knew be applied at once.

Failure as the Beginning of Purpose

Early in my life, I failed repeatedly. I lost businesses, status, and nearly lost my will to live. Standing at the edge of despair, I made a decision that changed everything. I would treat my life as an experiment, devoting it entirely to solving problems for all humanity, not for personal gain. From that moment forward, I stopped asking what would succeed in the market and began asking what was truly needed.

The Capstone Is the Problem, Not the Product

I never believed in isolated inventions. A chair, a house, or a dome means nothing unless it fits into a system. Every major project I pursued required mathematics, engineering, material science, economics, energy efficiency, and human behavior to work together. A true capstone project is not judged by appearance but by performance. Does it use fewer resources? Does it serve more people? Does it fail less often than what came before?

Design Science and Real-World Constraints

I called my approach design science. This meant solutions had to obey the laws of physics, economics, and human reality. A good idea that could not be built was not a good idea. The geodesic dome emerged not from artistic ambition, but from studying nature’s efficiency. I observed how strength could be maximized while material use was minimized. This is the discipline of capstone work: elegance born from constraint.

Serving Humanity, Not Institutions

Many of my proposals challenged governments, corporations, and traditions. I was often ignored or misunderstood because my work threatened established systems. Yet I persisted, because capstone projects must answer to outcomes, not approval. Housing shortages, energy inefficiency, and waste were not abstract problems. They were measurable failures demanding redesign.

Iteration Without Ego

Very few of my ideas worked perfectly the first time. I documented everything, improved relentlessly, and invited critique. I did not see revision as weakness. I saw it as proof that the system was alive. A capstone project that cannot evolve is already obsolete.

The Responsibility of the Solver

I believed deeply that technology is neutral, but intention is not. Powerful tools placed in careless hands can accelerate collapse as easily as progress. Therefore, every solution carries moral weight. If you design something that works, you must ask whom it serves and whom it excludes. The true success of a capstone project is measured by how many lives it quietly improves.

A Life as a Living Capstone

My work never ended, because the problems never ended. I leave behind not a single monument, but a framework for thinking. Start with the biggest problem you can responsibly address. Gather every discipline required. Respect constraints. Design for efficiency, equity, and resilience. Then release the solution to the world and let it be tested by reality.

Building a Capstone AI Project with Real-World Impact – Told by Fuller

If you start by asking what an AI tool can do, you have already limited yourself. I always began with the problem that refused to go away. Hunger, inefficiency, wasted effort, lack of access—these are not technical curiosities, they are system failures. A true capstone project does not exist to showcase capability. It exists to relieve pressure on reality where reality is failing people.

Choose One Problem Worth Finishing

Many students scatter their effort across many small ideas. That may feel productive, but impact comes from concentration. A capstone demands commitment to a single, clearly defined problem. Whether the challenge is financial literacy, education access, small business automation, historical preservation, or community engagement, it must be specific enough to measure and broad enough to matter. If the problem is vague, the solution will be decorative.

Think in Systems, Not Features

Real-world problems do not live in isolation. They exist inside systems of people, resources, incentives, and constraints. A strong capstone project connects multiple AI tools because the problem itself demands it. Writing, visuals, data analysis, automation, and communication are not separate tasks; they are interdependent functions. The goal is not to stack tools, but to integrate them so each supports the whole.

Design for Reality, Not Ideal Conditions

I never trusted solutions that worked only in perfect environments. Your capstone must survive limited budgets, imperfect users, incomplete data, and changing conditions. Ask what breaks first and redesign accordingly. AI makes iteration faster, but it does not excuse fragility. A project that works imperfectly in the real world is more valuable than one that works flawlessly in theory.

Measure Impact, Not Effort

Effort feels meaningful, but outcomes matter more. A capstone project should define what success looks like in measurable terms. Did understanding increase? Did time decrease? Did access expand? Did waste shrink? Impact turns a project from an assignment into a contribution. Without measurement, improvement cannot be verified.

Document Decisions, Not Just Results

A finished product tells only part of the story. What matters equally is why decisions were made. Which approaches failed. Which assumptions were wrong. Which tradeoffs were accepted. Documentation transforms a project into a learning system others can build upon. Progress accelerates when thinking is visible.

Release the Project to Be Tested

A capstone that never meets the public is incomplete. Once released, the project will encounter feedback, misuse, and unexpected outcomes. This is not failure. This is validation. Reality is the final reviewer. The purpose of design is not approval, but adaptation.

Responsibility Is the Final Requirement

Every powerful solution carries consequence. AI increases scale, and scale increases responsibility. Before calling a capstone complete, ask who benefits, who is excluded, and what happens if it spreads widely. A project that solves a problem while creating a larger one has not finished its work.

A capstone worthy of the future does not ask, what can I build? It asks, what must be improved—and am I willing to take responsibility for the answer.

Hosting and Deploying Interactive AI Projects

A screenshot proves something existed once. A live project proves it works. When portfolios move beyond images and descriptions into interactive experiences, they cross a threshold. Hosting and deployment turn ideas into systems that can be tested, shared, and improved. This shift is what separates a learner from a builder.

Why Hosting Matters

Publishing work publicly introduces accountability. When someone else can click, type, or explore your project, assumptions are tested immediately. Errors surface. Clarity matters more. Hosting forces precision, and precision sharpens thinking. This is why live demos carry more weight than polished explanations alone.

Understanding Repositories Without Fear

At first, repositories feel intimidating. In reality, they are simply organized records of work over time. GitHub allows students to show not only what they built, but how it evolved. Version control tells a story of iteration, problem-solving, and persistence. Each commit is evidence of progress, not perfection.

Turning Models Into Experiences

Some projects are best shared as interactive demos rather than raw code. Hugging Face makes it possible to present models, chatbots, or AI-powered tools in a way others can actually use. This accessibility shifts focus from technical complexity to practical usefulness.

Rapid Prototyping and Live Testing

For students who want to move quickly from idea to execution, Replit removes many barriers. Code runs instantly, collaboration is simple, and updates appear in real time. This environment encourages experimentation and makes iteration visible, which is exactly what a strong portfolio should highlight.

Linking Projects Into a Cohesive Portfolio

Live links transform a portfolio into a map of experiences. Each project becomes a doorway rather than a description. I encourage students to explain what the viewer should try, what problem the project addresses, and what stage it represents in their growth. Context turns exploration into understanding.

Embracing Imperfection in Public Work

Public projects do not need to be flawless. In fact, visible limitations often strengthen credibility when they are acknowledged honestly. Explaining what is unfinished or experimental shows awareness and maturity. Growth-oriented builders are trusted more than those who pretend completeness.

Deployment as a Skill, Not a Finish Line

Hosting a project does not mean it is done. It means it is alive. Updates, fixes, and refinements are part of its story. When students treat deployment as an ongoing process, their portfolios reflect real-world practice rather than classroom simulation.

Interactive work invites interaction. When someone can use what you built, your portfolio stops asking for attention and starts earning it.

Documenting Process, Not Just Results

A finished product is easy to admire and easy to misunderstand. Without context, it looks effortless or accidental. What employers, educators, and collaborators truly want to see is how you think when things are unclear. Process reveals judgment, adaptability, and persistence—qualities no final result can fully capture on its own.

Drafts Are Evidence of Intelligence

Early drafts are not embarrassments; they are proof that thinking occurred. I encourage students to keep versions that show ideas taking shape, changing direction, or being refined. These drafts demonstrate growth. They show that clarity was earned, not generated instantly. In a portfolio, this history builds credibility.

Failure Is Data, Not Disqualification

Most meaningful projects fail before they succeed. Tests break. Prompts misfire. Assumptions collapse. Documenting these moments transforms failure into insight. When students explain what did not work and why, they show analytical maturity. Avoiding failure hides learning. Naming it reveals competence.

Prompt Evolution Shows Control

With AI-assisted work, prompts rarely start strong. They improve through experimentation. Showing how a prompt changed over time demonstrates understanding of both the tool and the problem. This evolution proves that AI did not lead the project; it responded to it. Control is visible when refinement is intentional.

Testing Logs Tell the Real Story

Testing is where theory meets reality. Logs that record what was tried, what happened, and what was learned reveal discipline. Even brief notes show that results were examined rather than accepted blindly. This habit mirrors professional practice across fields and signals readiness for real-world work.

Reflection Turns Activity Into Insight

Reflection is where meaning forms. Asking what worked, what surprised you, and what you would do differently connects action to understanding. These reflections do not need to be long. They need to be honest. A few thoughtful sentences can transform a project from output into learning.

AI Amplifies Thinking, It Does Not Replace It

When process is documented well, it becomes obvious that AI is a tool, not an author. Good thinking leads to good outcomes faster. Weak thinking still produces weak results, only more quickly. Showing process makes this distinction clear and protects the integrity of the work.

Trust Is Built Through Transparency

Transparency builds confidence. When viewers can see how decisions were made, they trust the results more. Documenting process is not about exposing flaws; it is about demonstrating responsibility. In a portfolio, this openness sets serious thinkers apart.

Results may impress. Process convinces.

Ethics, Transparency, and AI Disclosure Statements – Told by Zack Edwards, Benjamin Franklin, and Buckminster Fuller

Zack Edwards begins by reminding readers that in an AI-driven world, trust is no longer automatic. When tools can generate text, images, code, and voices at scale, credibility comes from openness. Ethics cannot live quietly in intention alone; they must be demonstrated. A portfolio that explains how AI was used shows maturity. One that hides its methods invites doubt.

Franklin on Honesty as a Practical Advantage

Benjamin Franklin adds that transparency has always been a form of persuasion. In his time, trust determined whether ideas spread or failed. He argues that clear disclosure is not a confession of weakness, but a signal of confidence. When readers understand how a tool contributed and where human judgment took over, they are more likely to believe the outcome. Openness simplifies regulation because it leaves little to question.

Fuller on Responsibility at Scale

Buckminster Fuller widens the lens. AI increases reach, and reach increases consequence. A single project can now affect thousands. With that power comes responsibility to explain systems clearly. Fuller insists that disclosure is part of design itself. If users cannot understand how a system thinks, they cannot safely rely on it. Transparency is not optional when scale is involved.

What a Clear AI Disclosure Actually Includes

Together, they agree that a strong disclosure statement answers three questions. How was AI used? Where did human judgment matter most? What safeguards were applied? A brief explanation of prompts, revisions, and decision points is enough. The goal is clarity, not technical overload. Readers should walk away knowing who was in control and why.

Addressing Bias and Hallucinations Honestly

Zack emphasizes that AI is not neutral simply because it is automated. Bias and hallucinations are known risks. Ignoring them weakens credibility. Portfolios should briefly note how outputs were checked, corrected, or constrained. Acknowledging limitations shows responsibility, not incompetence. Franklin agrees, noting that admitting uncertainty has always been wiser than pretending certainty.

Future-Proofing in a Regulated World

Fuller points out that regulation always follows impact. Clear disclosures prepare students for a future where accountability will be expected, not optional. A portfolio that already documents AI use will age well. One that hides it may need rebuilding. Designing for transparency today avoids friction tomorrow.

Ethics as a Competitive Advantage

The discussion closes with a shared conclusion. Ethics are not a barrier to opportunity; they are a foundation for it. In a crowded AI landscape, trust differentiates serious thinkers from careless users. A portfolio that explains its methods signals readiness for responsibility.

When ethics are documented, transparency is practiced, and AI use is disclosed clearly, the work does more than impress. It earns confidence—and confidence is what allows innovation to last.

Presenting, Pitching, and Monetizing the Portfolio – Told by Zack Edwards, Benjamin Franklin, and Buckminster Fuller

Zack Edwards opens by framing the portfolio not as an archive, but as an invitation. Whether the audience is a panel, an employer, an admissions committee, or a potential sponsor, the portfolio’s job is to guide attention. A clear opening narrative, a concise walkthrough, and a defined outcome help the audience understand what problem was solved and why it matters. Presentation is not performance; it is orientation.

Making Value Obvious

Benjamin Franklin leans into practicality. He argues that a pitch succeeds when value is unmistakable within moments. The presenter should be able to answer three questions without hesitation: what did you build, who does it help, and why is it worth attention or investment? He cautions against jargon and excess detail. Brevity, clarity, and relevance convert interest into opportunity.

Demonstrating Systems, Not Slides

Buckminster Fuller insists that the strongest pitch shows a system at work. Live demonstrations, interactive elements, and measurable outcomes speak louder than claims. A portfolio that can be used, tested, or explored communicates readiness. Fuller emphasizes that a capstone defense is most convincing when the project survives real-world conditions, even imperfectly.

Adapting the Same Work to Different Audiences

Zack highlights that one portfolio can serve many doors if it is framed correctly. For a job interview, focus on skills and collaboration. For college supplements, emphasize growth and reflection. For business pitches, center outcomes and scalability. The work stays the same; the story adapts. This flexibility is itself a professional skill.

Turning Projects Into Paid Value

Franklin introduces monetization as proof of usefulness. A portfolio project can become a service offered to local businesses, a pilot startup, or a subscription-based tool. Even small revenue validates demand. He reminds readers that ethical monetization sustains good ideas and allows them to improve rather than disappear.

From Demonstration to Sponsorship

Fuller connects monetization to mission. Some projects are best supported through sponsorships or grants because their value is communal rather than commercial. Clear demonstrations of impact make it easier for organizations to support work aligned with their goals. A portfolio that shows results invites partnership.

Scholarships, Recognition, and Long-Term Growth

Zack notes that portfolios increasingly replace test scores and resumes. Clear documentation, live projects, and thoughtful presentation position students for scholarships and recognition. Over time, the portfolio evolves, but its role remains constant: it tells the story of capability becoming contribution.

Confidence Comes From Clarity

The discussion closes with agreement. Presenting well is not about confidence alone; it is about clarity. When the work is real, the impact is measured, and the purpose is clear, pitching becomes a natural extension of the project itself.

A portfolio that can be presented, pitched, and monetized is no longer just proof of learning. It is proof of readiness.

Vocabular to Learn While Learning About AI Portfolio and Capstone Project

1. PortfolioDefinition: A curated collection of work that demonstrates skills, growth, and capability over time.Sample sentence: My AI portfolio shows how my projects improved from early drafts to finished capstone work.

2. Capstone ProjectDefinition: A major, culminating project that applies multiple skills to solve a real-world problem.Sample sentence: Her capstone project combined AI writing, visuals, and data analysis to improve financial literacy.

3. NarrativeDefinition: The story that explains the purpose, direction, and meaning behind a body of work.Sample sentence: The narrative of his portfolio made it clear he wanted to become an AI-assisted educator.

4. IterationDefinition: The process of improving work through repeated testing, feedback, and revision.Sample sentence: Each iteration of the project solved a flaw discovered in the previous version.

5. DocumentationDefinition: Written records that explain how a project was developed, tested, and revised.Sample sentence: His documentation showed how human judgment guided every major AI decision.

6. Disclosure StatementDefinition: A brief explanation describing how AI tools were used and where human control mattered.Sample sentence: The disclosure statement explained which parts of the project were AI-assisted.

7. Version ControlDefinition: A system for tracking changes and updates made to a project over time.Sample sentence: Version control allowed reviewers to see how the project evolved.

8. DeploymentDefinition: Making a project live and accessible for others to use or test.Sample sentence: Deployment turned the chatbot from a concept into a usable tool.

9. Live DemoDefinition: A working version of a project that others can interact with in real time.Sample sentence: The live demo impressed employers more than screenshots alone.

10. MonetizationDefinition: Turning a project or skill into something that can generate income or funding.Sample sentence: She explored monetization by offering her AI tool as a paid service to small businesses.

Activities to Demonstrate While Learning About AI Portfolio and Capstone Project

Build a Mini Capstone Pitch – Recommended: Intermediate to Advanced Students

Recommended Age: 13–18

Activity Description: Students design a simplified capstone project focused on solving a real problem using AI tools.

Objective: To teach systems thinking and problem-first project design.

Materials:AI brainstorming toolPaper or slidesOptional visual or audio AI tools

Instructions: Students identify a real-world issue such as budgeting, learning access, or community awareness. They outline a solution using at least two AI tools. They prepare a short pitch explaining the problem, solution, tools used, and impact.

Learning Outcome: Students learn that capstone projects are about impact and integration, not isolated features.

Live Link or It Didn’t Happen – Recommended: Intermediate to Advanced Students

Recommended Age: 14–18

Activity Description: Students experience the difference between static work and interactive projects.

Objective: To introduce hosting, deployment, and accountability.

Materials:Computer with internetSimple coding or no-code platformAI assistant for troubleshooting

Instructions: Students create a simple interactive project such as a chatbot, calculator, or explainer page. They publish it so others can access it. Peers test the project and give feedback on clarity and function.

Learning Outcome: Students learn that deployment changes how work is judged and that live projects reveal strengths and weaknesses.

Portfolio as Opportunity Map – Recommended: Intermediate to Advanced Students

Activity Description: Students explore how portfolios can lead to jobs, scholarships, businesses, or sponsorships.

Objective: To connect learning with real-world outcomes and motivation.

Materials:Portfolio draft or project summaryAI brainstorming tool

Instructions: Students identify three possible outcomes for one project: academic, professional, and entrepreneurial. They outline how the same work could be presented differently for each audience.

Learning Outcome: Students learn that presentation and framing turn learning into opportunity.

Comments