1. Heroes and Villains of Ancient Africa: The Paleolithic Era (c. 300,000 BC – c. 10,000 BC)

- Zack Edwards

- Aug 5

- 44 min read

My Name is Tika the Fire-Keeper (Teen Inventor and Communicator)They call me Tika the Fire-Keeper, but I wasn’t always that. I was born during a season of storms. Thunder rolled across the sky, and lightning split the trees. Some say that’s why I’m so restless—why my hands always move and my mind runs ahead of my words. My mother told me I never cried as a baby, only watched the fire with wide eyes. She says I laughed the first time the flames danced.

Fire became my friend early. While other children played with sticks and mud, I sat near the coals, poking, shifting, feeding the flames. I learned what made it grow and what made it die. I learned the heat of dry wood versus green, the power of wind, the danger of letting it run wild. Fire spoke to me—not in words, but in flickers and crackles and warmth. And I listened.

Curiosity and Cuts

I ask questions. Too many, according to Omu. “Why do leaves curl when they burn?” “What happens if you hit bone with stone?” “What if we tied the stone to the stick with sinew instead of plant cord?” I broke more tools than I fixed. I burned my fingers more times than I can count. Once I cut my leg trying to sharpen a flint blade in a new way. The others laughed—until the tool worked better than the old one.

Sena says I’m reckless. He’s right. But he also says I see what others don’t. I once made a throwing stick that curved in the air. Useless for hunting, but it made the children laugh when it came back to me like magic. Maku said maybe it was a message from the spirits. Maybe. But I think it’s just fun.

Keeper of the Flame

I earned my name the day the fire nearly died. We were traveling, following the herds, and a cold rain soaked our coals. Everyone panicked. No dry wood. No spark. We huddled together, wet and shivering. That night, while others slept, I stayed awake, breathing into a tiny ember buried in dry moss under my cloak. I fed it gently, whispered to it, shielded it from the wind with my hands and breath. By morning, it caught flame.

They gave me the name Fire-Keeper. Not just because I saved the warmth, but because they saw how I tend it—with care, wonder, and stubbornness. Fire is alive, and I am its friend.

Ideas That Burn Bright

I don’t just keep fire—I play with it. I use it to shape new tools, to harden wooden points, to test stones. I discovered that when you heat certain rocks, they crack better. When you drop water on hot stone, it explodes—dangerous, yes, but thrilling. One day, I hope to shape fire itself—to make it travel without wood, or light without smoke.

I dream of things the others haven’t seen yet. I once tied a shell to a hollow reed and blew into it until it howled like a beast. The children scattered, and the elders told me to stop summoning spirits. But Maku smiled. She said dreams begin in sounds like that.

Words in the Wind

They also ask me to speak. I tell stories around the fire—of how Sena fought the bear, or how Omu healed a hunter with a crushed foot using moss and willow bark. I act them out, use my voice to mimic the roar of beasts and the whisper of leaves. I don’t just tell stories—I become them.

Maku says this is the beginning of language beyond survival. She says I’m a bridge between what was and what could be. I like that. I don’t want to just repeat what the elders did—I want to go further, burn brighter.

The Road Ahead

I’m still young. I know I’ll make mistakes. My hands are scarred from burns. My legs are scratched from running where I shouldn’t. But I wake up every day eager to try again, to test, to ask, to build. I want to see beyond the next fire, to know what’s waiting in the smoke.

Someday, I’ll teach others. I’ll show them how to ask questions, how to fail and try again. I’ll pass on the fire—both the one that warms and the one that drives us forward.

Because to be Paleolithic isn’t just to survive. It’s to wonder. And for me, wonder burns hotter than any flame.

The First Sparks of Stone: Making and Using Stone Tools – Told by Tika

I was never one to sit still, especially not when there was something sharp nearby. As a child, I watched Sena chip stone under the sun, shaping it into a hand axe. The clink of stone against stone filled the air, steady and careful. I sat beside him, mimicking the motion with my own rounded rock. My fingers were clumsy at first. I bloodied them more than once. But something about the rhythm caught me—the way a single strike could split stone, the way a dull edge could be coaxed into something sharp.

Our tools were not born perfect. They came from mistakes. From cuts and splinters and wasted pieces. But we kept trying. We had to. Because without tools, we had no claws, no fangs, and little hope of keeping up with the great beasts that roamed the world.

Hand Axes: The Foundation of Fire and Flesh

The hand axe was our oldest friend. A chunk of flint or basalt, shaped on both sides to a point—wide in the palm, narrow at the edge. We used it to cut meat, scrape hides, split wood. Some were as big as my forearm, others small enough for a child to carry. I made my first working one when I was seven summers old. It wasn’t pretty, but it sliced through bark, and I carried it with pride.

We shaped them using percussion flaking. That’s a fancy way of saying we struck the stone with another, often a round hammerstone. Sometimes the flakes came off just right—thin, curved, like sharp petals. Other times, the rock would crack wrong or shatter entirely. But over time, I learned to feel the grain of the stone. To strike not too hard, not too soft, but just right. The rock speaks if you’re patient.

Scrapers: The Silent Workers

After the hunt, the scrapers came out. These tools were smaller, flatter, with an edge like a crescent moon. We used them to strip flesh from bone, to clean hides, to smooth wood. I liked making scrapers more than axes. There was elegance in them. Precision.

The best ones came from flint and obsidian, though obsidian was rare and dangerous—it shattered into razor-like shards. I once cut a line across my palm trying to shape it. Omu wrapped it in moss and muttered about foolish hands. But even she admitted later: the tool I made from that stone could clean a hide twice as fast.

We discovered better edges by breaking things. That’s the truth. By failing again and again. Then someone—maybe by accident—struck a core stone at a new angle, and a perfect blade slid off like magic. We learned to look for that angle, to repeat it, to pass the technique on.

Spears: The Leap to the Hunt

But it was the spear that changed everything. Tying a sharpened stone point to a wooden shaft turned us from scavengers into hunters. It let us strike from a distance, pierce thick hides, and defend ourselves from beasts with teeth longer than a hand.

At first, we just wedged sharp flakes into notches. But they slipped. So we used sinew—twisted strips of animal tendon—to bind the stone to the shaft. Then came pitch, heated and sticky, to glue it in place. Fire helped here too. Everything was better with fire.

The first time I made a spear that flew straight and stuck deep into a straw-stuffed hide, I felt like the stars had opened. It meant we didn’t have to get so close. It meant we could chase bigger prey. It meant fewer broken ribs and more meat in the cook pit.

Stone That Taught Us

Every chipped edge, every bloodied thumb, every broken blade taught us something. We learned which rocks shattered too easily, which held their edge, which sparked when struck. We came to favor flint, chert, quartzite—and in the rarest times, obsidian. Each tool we made made us more than we were before.

I still sit by the fire sometimes, chipping at stone, dreaming up new shapes. A curved blade that fits the hand better. A smaller, lighter spear point. A scraper with a notched grip.

Because even now, we’re still learning. Still shaping. Still striking stone and listening for the right sound. In every tool, there is a story. And every story begins with the spark of an idea—and the courage to try, and fail, and try again.

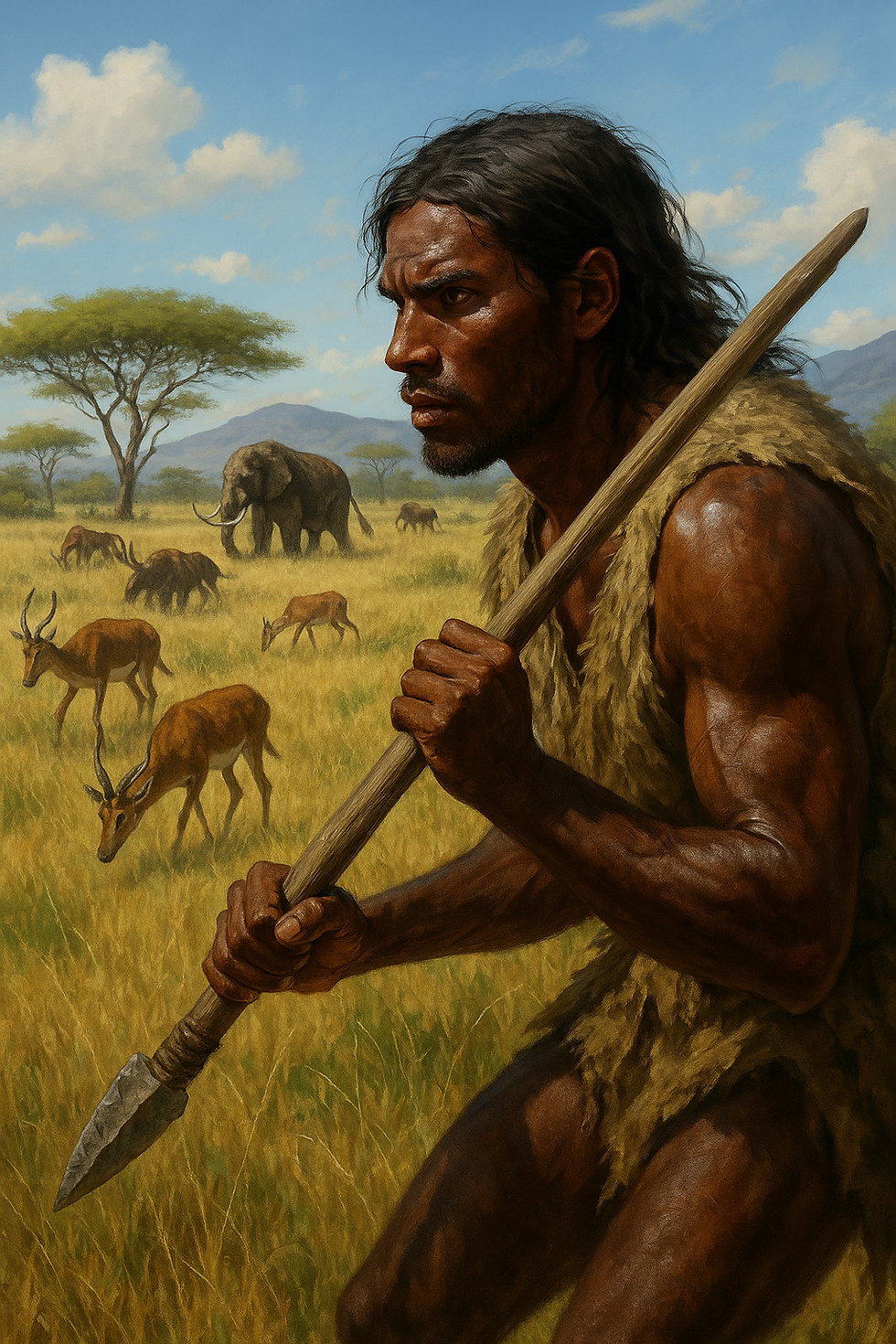

My Name is Sena the Tracker (Hunter)

I was born in the shadows of towering glaciers, when the earth still groaned with cold and the breath of winter filled every cave. My mother said the sky wept snow the day I arrived, and that a fire had to be kept burning day and night just to keep me alive. We lived near the edge of a forest that never stopped whispering, where great elk left their tracks in soft moss and the wolves followed close behind.

From the time I could stand, I followed my father and uncles, their legs strong as tree trunks and their eyes sharp as hawks. They were the hunters, the providers, and I wanted nothing more than to run beside them, spear in hand, through the fog-draped mornings of our world.

Learning the Ways of the Hunt

I learned first by watching. How they crouched beside broken twigs or fresh dung and saw stories in the dirt that I could not yet see. How they could smell the air and know if the bison were near, or if danger stalked us instead. I practiced with a short spear, tossing it at logs and stumps until my arms ached and my shoulders burned.

Then came my first hunt. I was ten summers old, and it was for a wild boar—fierce, tusked, fast. I trembled behind the brush while my uncle circled it, driving it toward me. When the moment came, I threw true. The spear struck its shoulder. It did not fall—but it slowed. My father finished the kill. He gave me the tusk to wear around my neck. I still do.

The Long Walks

A hunter does not stay in one place. Seasons shift. Herds move. So we followed. Across wide plains, up rocky hills, along frozen rivers that cracked beneath our feet. Each step, we listened to the earth. We watched the skies, read the wind, marked the movement of birds and insects. The world spoke, and over time, I learned its language.

Some lands were kind—rich with red deer and rabbits. Others tested our will—scarce, dry, crawling with snakes and shadows. I’ve seen men fall from hunger. I’ve buried a friend whose foot slipped on a cliff's edge. The land gives, and it takes.

The Beast and the Boy

There was one winter, perhaps ten years ago, that marked me more than any other. We had tracked a giant cave bear for three days. The beast was old, scarred, and clever. It doubled back. When I entered the cave mouth, it was waiting. My spear struck, but the creature surged forward. It slashed my leg, sent me crashing into the rocks. I would have died, had not a boy—Tika, barely thirteen—lit a firebrand and waved it in the beast’s face. Fire frightened it long enough for the others to return.

I still limp in the cold months. But that scar reminds me: survival is not about strength alone. It is about trust, timing, and the courage of those beside you.

Hunting with Respect

I have killed many animals. But I do not do so in hatred or waste. Each kill is followed by ritual. A word of thanks. A touch to the earth. We use the whole creature—the meat, the hide, the bones, the sinew. Nothing is taken without giving.

Maku the Dreamwalker says the animals speak to the stars, and their spirits follow us. I do not know about stars, but I have felt the gaze of a great stag as it fell, and I knew I had taken something sacred.

Teaching the Next

Now I teach the young. I show them how to move without sound, how to find water when the rivers vanish, how to read a trail and feel the presence of a hidden predator. Some are eager. Some too proud. But all must learn that hunting is not about domination—it is a dance, one as old as fire.

Omu teaches them the plants. Tika shows them fire and tools. Maku shows them dreams and visions. I show them how to move through the world without becoming lost in it.

My Place in the Circle

I do not know how long I will walk these paths. My joints ache. My eyes are not as sharp. But each morning I wake to the scent of smoke and the sounds of life—children laughing, fire crackling, elders murmuring. I know the clan endures.

And when my body returns to the earth, I hope my stories remain. That the young ones remember Sena, who once ran with the wolves, followed the bison, and listened to the wind.

For in the Paleolithic world, to live is to listen—to the land, the animals, and the silence between them.

The First Track: Tracking and Hunting Game – Told by Sena

The first time I followed a trail, I was barely old enough to carry a spear. My father pointed to the ground and asked me what I saw. I said, “Nothing.” He said, “Look again.” I looked harder. The earth was soft with recent rain, and I noticed a single hoofprint pressed into the mud, half full of water. Then I saw the broken grass, the rub of fur on a low branch, the faint scent of musk in the air. That was the first lesson: the animal does not want to be found, but it leaves its story behind anyway.

Tracking is not a skill you learn in a day. It is a conversation with the ground, the trees, the wind. You have to ask questions with your eyes and ears, and listen with your whole body. It begins with a print and ends with a heartbeat.

Stalking the Prey

Once you find the trail, you must become a shadow. No snapping twigs. No sudden moves. You step where the prey stepped, feel where it felt heavy or frightened. A frightened animal runs in a straight line. A calm one meanders. If the prints change, if they deepen or space out, you know something spooked it—maybe a scent, a sound, or your presence.

When I stalk an animal, I breathe slowly, like I’m sleeping. My feet roll from outer edge to toe. I blend into the brush, becoming a part of the forest, not an intruder. If a bird calls out in alarm, I stop. If the wind shifts against me, I wait. Animals live by their ears and noses. You must move like the wind and smell like the earth.

Once I followed a deer for a full day, moving when it moved, resting when it rested. I only threw my spear when I could see the breath rise from its nostrils in the cold air. And when it fell, I whispered thanks, because I had learned more from that deer than from many men.

The Traps We Set

Not every kill comes from a chase. Some come from patience and clever hands. We set traps—pits covered with branches and leaves, snares woven from sinew or vine, deadfall logs that crush with weight and speed. But traps only work if you understand the path of your prey. Where does it drink? Where does it sleep? Where does it feel safe?

I once built a snare near a berry patch where I saw fresh droppings. It caught nothing for three days. On the fourth day, I noticed the tracks had shifted—just a few feet, where the animals had begun to walk around the scent of my presence. I moved the snare and caught a rabbit the next morning. The lesson was simple: they’re always watching too.

The Dance of the Group Hunt

Some hunts are too dangerous for one hunter alone. That’s when the group comes together. We plan the movement like a dance—two approach from the east, where the sun blinds the prey. One drives the herd from the back. One waits in silence near the river crossing. Every step is part of a larger picture. Every shout, every footstep, every pause has meaning.

We use hand signals, whistles, bird calls. We mimic the sounds of animals to distract, to calm, to confuse. When the bison herd moves, we move with it. When they turn, we guide them into a narrow pass or toward the trap we’ve dug days before.

The kill in a group hunt is not just for the one who throws the final spear. It belongs to all—those who drove the herd, those who stayed up late watching for movement, those who made sure the spears were sharp. A successful hunt is not about pride. It’s about survival.

Patience is the Sharpest Weapon

There are days when we return with nothing. The prey vanished. The weather turned. The scent betrayed us. But we don’t complain. We wait. We learn. We prepare for the next time. That is the way of the hunter.

Impatience makes noise. Impatience spooks prey. I have seen young hunters rush in, heart racing, only to throw too early or too far. The animal escapes, and the silence afterward is heavier than stone. But patience—that brings the kill. Patience sharpens the eye and stills the breath.

Knowing the Animal

To hunt is to know. You must know the animal not as an enemy, but as a brother. Know its habits, its fears, its strength. The boar charges when cornered. The elk runs into the wind. The rabbit freezes before it flees. If you know what it will do, you already know where to be.

I once sat for hours watching a wounded fox limp to a burrow. I did not kill it. I just watched. When it died days later, I buried it with my own hands. That, too, is part of the hunt—knowing when not to throw.

The Hunter’s Way

I walk in silence. I breathe with the wind. I watch the earth for its stories. When I hunt, I do not see beasts. I see teachers.

In the Paleolithic world, the hunter is not a killer alone. He is a listener, a learner, a guardian of his people. My spear is sharp. But sharper still is the stillness I carry within me. And when the prey falls, I do not cheer. I kneel, and I remember that it gave its life so we could live. That is the hunter’s way.

My Name is Omu the Gatherer (Elder Mother/Knowledge Keeper)

I was born beside the river where the bark peels like sunburnt skin and the frogs sing louder than the wind. My mother named me Omu, after the low sound she made when she hummed to me as a baby. She said I was quiet, but I watched everything. While others crawled toward firelight or food, I reached for leaves. I pulled them close and tasted them when no one was looking. I learned early what made the tongue sting, the belly cramp, or the skin itch.

Our clan wandered then, like all clans do, but the river always called us back. It was my first teacher. I followed its bends and banks with bare feet, collecting berries, seeds, bark, and roots. I asked questions—not with words at first, but with hands. I crushed leaves. I sniffed sap. I watched the bees, and they taught me where sweetness lived.

The Plants and Their Secrets

Not all learning comes from people. The plants speak, too. Some shout with bright berries, others whisper through scent or sting. My aunt taught me the first rules: if it smells like death, trust your nose. If the birds don’t eat it, neither should you. If it burns your tongue raw, spit and run for the river.

I was fifteen when I found a vine that bled red. I ground its root, boiled it with willow bark, and gave it to a boy burning with fever. The next day, he stood and ate a full meal. My aunt smiled, but said nothing. That night, she placed her herb pouch in my lap. The next morning, she walked into the woods and did not return. Her way of saying I was ready.

Mother to Many

I had children of my own—three strong girls and one quiet boy—but I mother more than I birthed. In the clan, the young crawl to me when their stomachs ache or when they find a strange nut they want to chew. I scold them, laugh with them, feed them. When a woman gives birth, I am there. When someone dies, I clean their skin with oil and leaves.

I watch the seasons and know when the tubers swell, when mushrooms rise after rain, when the bitter greens turn sweet. I carry the knowledge of the land in my bones. And now, I teach others to carry it, too.

The Rhythm of the Earth

There is a rhythm to life that few hear anymore. The young run fast, chase the hunt, shout into the wind. But the earth moves slowly, patiently. I walk with that rhythm. I feel when it is time to dig and when it is time to let the roots rest. I feel when a storm is coming in my knees, and when the river will flood in my dreams.

I’ve seen many moons. I’ve buried lovers and friends. I’ve held dying hands and new breath. Life and death walk side by side, and both deserve care.

The Fire of Memory

Tika says fire is life. He is right. But memory is fire, too. The memory of how to prepare bark poultice, how to mash acorns so they don’t poison us, how to grind seeds with stone and patience. I am the fire of memory. When I die, some flames may fade—but I do not fear death. I only fear forgetting.

That is why I speak. I speak to the girls when we walk the woods, to the boys when they cut themselves with sharp stones. I speak to Maku when she paints the walls, so the plants are remembered in color and form. I speak to Sena when he brings me fresh meat, so I can tell him which leaves will keep it from rotting. I speak to the wind, sometimes, when no one listens. But even then, I hope the trees hear me.

The End is Also a Beginning

One day, my pouch will pass to another. My knees already ache in the cold, and my fingers don’t grip like they used to. But I still walk. I still gather. I still hum the old songs as I grind roots into powder.

I am Omu, child of the river, speaker of plants, mother to many. My story is not one of great hunts or fires saved from rain—but it is a story of care, of wisdom, of things that grow in silence.

In the Paleolithic world, it is not only the hunters who keep the clan alive. It is also those who listen to the leaves, who know which berry feeds and which one kills, who teach with hands and with love. And when my body returns to the soil, I hope the seeds I planted—in earth and in minds—will still grow.

The Plants Speak First: Foraging and the Plant World – Told by Omu

Before the hunters bring meat and before the fire roasts bone, there are always the plants. They are quiet, patient, and everywhere. The land offers them freely, but only to those who listen. I have listened all my life. The plants have been my teachers, my healers, my companions. When I was a girl, too small to carry tools, I carried a basket. I followed my mother through meadows, riverbanks, and forests, and she whispered to me the names of things. Bitterroot, yarrow, wild onion, elderberry. Some were friends. Others were dangerous strangers.

The Taste of Life and Death

A mistake with plants can bring sleep that never ends. I remember the first time I saw a child with foaming lips, eyes wide with fear. She had eaten red berries that grew in a cluster low to the ground—bright, beautiful, and deadly. Her mother screamed. I ran for the willow bark and ground it into a bitter tea, hoping it would draw out the poison. She lived, but barely. After that day, I never forgot the lesson. Color and sweetness do not always mean safety.

We learn the plants through testing, but also through watching. What do the birds eat? What do they avoid? Which berries stain the tongue? Which roots give energy, and which twist the belly? My tongue has known pain more than once from tasting unknown greens. But with each mistake, I added to my memory. Now, when I walk, I see not just plants, but stories. This leaf cools a fever. This bark stops blood. This flower draws bees and can soothe the eyes.

Gathering with Purpose

Foraging is not a scramble. It is a rhythm. Each season brings different gifts. Spring gives us fresh greens—nettle, dandelion, wild garlic. Summer bursts with berries—blue, black, red, each with their own time. Autumn fills our baskets with roots and seeds—acorns, cattail, wild carrots, the swollen bulbs of camas and onion. We never take everything. We leave some for the animals, some for next year. The land must always be thanked.

I carry a digging stick, smooth and worn with age. It is my companion. With it, I lift roots gently, so as not to break them. I shake soil back into the earth and speak soft words as I gather. My basket is woven with care, wide at the mouth and strong at the base. It has held thousands of meals.

The Circle of Sharing

What we gather is never ours alone. Everything is shared. After the morning forage, we return to the camp and spread our harvest on hides or mats. Children help sort the berries. The old ones inspect the roots. Seeds are ground on stones by steady hands. Some are roasted, some boiled, some dried for the cold moons.

In our world, there is no hoarding. If a person gathers only for themselves, the land will stop speaking to them. I’ve seen it happen—those who forget others find only bitter leaves and empty soil. But those who share are always guided. When someone is ill, we prepare medicine from the plants. When a child is hungry, the best nuts and fruit are given to them first.

Teaching the Young

Now, as my hair turns white and my hands tremble slightly, I walk with the youngest ones beside me. I show them which plants to pick and which to leave. I teach them the feel of good bark and the smell of rot. I let them taste small bites under my watchful eye. I test their memory with songs—each plant has a song—and they hum as we walk.

I tell them stories. Like the time Tika nearly poisoned himself with red nightshade berries until I slapped them from his hands. He still blushes when I mention it, but he also knows now how to spot them by the shape of the leaf.

The Gift of the Earth

We are not just gatherers of food. We are caretakers of the land’s wisdom. Every root dug, every seed planted, every berry picked and shared is part of a long conversation between people and earth.

In the Paleolithic world, the hunt may feed the belly, but the plants feed everything else—our health, our rituals, our quiet moments by the stream. And in those quiet moments, when the wind stirs the grass and the trees sway like old mothers dancing, I feel the plants still whispering to me.

I listen, as I always have. And I teach, so their voices never fade.

The First Flame I Called: Fire and Shelter – Told by Tika

The first time I made fire, real fire, on my own, I cried. Not because I burned myself—though I did—but because I had made something alive. I was twelve. Sena had taken the hunters out. Omu was gone gathering. A storm was coming, and our fire had died during the night. The coals were cold. Everyone looked to me. I took my fire kit—a dry spindle, a fireboard, and a nest of dry grass—and worked until my palms blistered.

At first, nothing. Then, smoke. Then a spark. Then the grass glowed and flared. I blew gently, whispering like Omu taught me. The flame rose, orange and proud. I fed it bark and sticks and soon, the cave was filled with light again. That night, the elders called me Fire-Keeper. And I have never let that flame die since.

How We Start the Flame

Fire does not come easily. It must be earned. We use a bow drill now—easier on the hands, faster to spin. I twist a cord of sinew around a straight stick, place one end in the notch of a fireboard, and draw the bow back and forth. The stick spins fast, grinding into the base. Smoke curls upward, and if you’re lucky—or patient—a coal forms. You drop that glowing coal into a nest of bark, moss, dry grass, and blow. Slowly. Gently. Fire is a baby when it’s born.

There are other ways too. Flint and pyrite can spark if struck just right, but the spark must catch on something very dry. Omu says long ago, someone saw lightning strike a tree and carried the flame. Maybe that’s where it all began.

Keeping the Fire Alive

Starting fire is hard. Keeping it alive is harder. We protect it like we protect the youngest child. In wind, we build a wall of stone. In rain, we shield it with hide or bring it deep into the cave. At night, we cover the coals with ash, keeping them warm but quiet. In the morning, we blow gently to wake them again.

When we travel, we carry the fire in hollow horns filled with embers and moss. I walk near the front, checking it constantly. If it dies, we must stop and make another. And if the wood is wet or the wind unkind, we may be cold a long while.

What Fire Gives Us

Fire is more than heat. It is light. It pushes back the dark. Before fire, the world ended at the edge of sunset. With fire, we can see, speak, and dream long after the sun sleeps.

It cooks our food. Meat is no longer just blood and bone—it becomes soft, rich, warm. We boil roots to soften them, roast nuts to crack them. Fire makes bitter things sweet and hard things edible. We burn bones for warmth and chew the soft ends to draw out the marrow.

Fire protects us. No beast comes too near the flame. Even the great cat with glowing eyes stays in the shadows. Around the fire, we are not just safe—we are together. Stories live by firelight.

Building the Shelter

When we settle for more than a night, we build. The land tells us how. In the forest, we use bent saplings lashed with vine to make a dome. We cover it with bark or hide. On open plains, we build low and wide, anchoring with stones and staking hides against the wind. In cold places, we use bones—mammoth ribs curved into arches—covered with thick furs.

Inside, we spread soft grass or woven mats. We dig a shallow pit for the fire, with a hole at the top to let the smoke rise. The heat stays close, bouncing from hide to stone to skin. When the cold howls outside, the inside stays warm, glowing like a quiet sun.

The Shelter Is the Heart

I love the fire, but the shelter is its shell. Without one, the wind steals your warmth, and rain laughs at your spark. A well-built shelter hums in the wind but does not fall. It is where we rest, love, eat, and wait. It is where new life begins and old life passes.

When I build a shelter now, I think not just of bones and hide, but of who will sit inside it. Will a mother warm her baby by the flames? Will Omu grind seeds in the corner? Will Sena return with blood on his spear and stories in his eyes?

Home Is Where the Flame Breathes

Fire and shelter. One breathes, the other protects. Together, they are life. They are more than survival. They are comfort. Memory. Home.

In the Paleolithic world, we may not have stone walls or towers. But we have fire. We have warmth. And wherever we carry that spark, and wherever we build around it, we make a home. Even in the coldest dark.

The Sky Changes Everything: Migration and Climate Change – By Sena and Omu

The sky was gray that morning. Not the usual kind of gray—the soft, gentle one that brings mist and the scent of wet earth. No, this was a cold gray, sharp and biting, with wind that carried the smell of distant ice. I sat sharpening my spearhead when Omu joined me, a basket of roots on her hip and her cloak drawn tight.

“You feel it too?” she asked.

“I do,” I said. “The air smells of change.”

She sat beside me, staring at the horizon. We’d seen it before—cold seasons that stayed too long, warm ones that vanished too quickly. But this one felt different. We both knew it.

When the Ice Came

Omu’s voice was quiet, like wind through dead leaves. “I remember, long ago, when the rivers stopped flowing and turned to stone. The earth cracked beneath our feet. We had to leave the valley. The berries shriveled. Even the moss died.”

I nodded. “The herds left too. We followed, but the snow kept falling. It took my brother that year. We found no firewood. No shelter. Just wind and white.”

She looked at me, her eyes lined with years. “We forget that the land is not ours to stay on forever. When the cold comes, we must move. When it warms, we must move again.”

I looked to the north, where the old trails had vanished beneath thick snow. “The world breathes,” I said. “In and out. Ice comes like a long breath in. And when it exhales, the rivers return and the animals walk again.”

Chasing the Herds

I threw a small stone, watching it skip. “We follow the herds because they know what we do not. They feel the grass rise before it does. They sense the water beneath the soil. If the reindeer turn west, we turn west. If the bison move to the hills, we move too.”

Omu smiled. “They are our guides, though we pretend we guide them.”

I thought of last spring, when the mammoths returned after two years gone. Their paths carved deep grooves into the thawing ground. We had waited and watched the skies. And when they came, we rejoiced—not for the meat alone, but because they brought the rhythm of the world with them.

Omu placed a hand on my knee. “It is not just the hunters who watch. The gatherers do too. The roots grow where the sun lingers. When the sun shifts, so do the plants. The food moves, and we follow.”

Across the Continents

I’ve walked far in my life—across plains that stretched longer than a full moon’s rise, through forests older than my clan’s memory. I’ve seen rivers frozen so hard you could walk across them like dry stone, and I’ve seen those same rivers turn to raging floods when the warm winds came back.

Omu added, “My mother told me that her people once came from beyond the great water. They followed the land bridge, chasing beasts and summer berries. When the ice grew again, it swallowed the path. That bridge is gone now, beneath the waves.”

I looked at her in surprise. “So even the sea once gave us roads?”

She nodded. “Everything changes, Sena. What is dry now may flood. What is cold now may burn. We do not own the land. We walk it, for a time.”

Teaching the Young

Later that night, I sat by the fire and watched Tika ask Omu where we would go next if the hills stayed dry. She told him gently, “You listen. To the wind, to the animals, to the plants. They will tell you when to leave. Not all at once. But if you listen, you’ll know.”

I added, “And don’t fear the path. We've walked paths since the beginning. Every place we’ve called home was once new, once strange.”

Tika nodded, wide-eyed. He would learn. He already had the fire in his hands. He would need the patience in his feet.

The Path We Walk Together

In the Paleolithic world, the land is not still. The earth shifts. The sky changes. The cold returns, then fades. And we move—not because we are weak, but because we are wise. To follow is not to flee. It is to live.

Omu and I rose together that night and looked out over the hills. She placed her hand on my shoulder and said, “When we leave this place, we will find another. And there, the fire will burn again. The roots will grow. And the stories will continue.” And so they do.

My Name is Maku the Dreamwalker (Spiritual Leader)

They say I was born beneath a moon that vanished. The sky was dark, the stars hidden, and a strange stillness sat over the land. My mother cried in silence. My father stood at the cave mouth, watching for signs. When I came into the world, no one spoke. The fire flickered blue. They named me Maku, which means silence after thunder.

Even as a child, I heard things others didn’t. Not voices, not exactly—more like feelings that pressed into my chest. When someone was about to fall sick, I felt it. When a hunt would fail, I dreamed it. I would wake before sunrise and sit in the ashes of the fire, drawing shapes in the dirt that I didn’t understand but couldn’t stop drawing. The elders watched me from the corner of their eyes. Some feared me. Some just waited.

The Cave of Paint and Smoke

My first vision came during a fever. I was nine. My body burned like a dry log in flame. They thought I would die. But instead, I rose in the night and wandered to the far end of our cave, where even the bravest children wouldn’t go. I crushed charcoal with a stone, mixed it with spit, and painted a spiral on the wall. When they found me, I had collapsed beneath it.

That morning, I spoke of things I couldn’t know—of a great storm that would drive the elk west, of a mother who would birth twins, one still and one screaming. Both things came true. After that, they stopped calling me strange. They started calling me Dreamwalker.

Between the Worlds

I do not hunt, though I’ve tracked the blood trail of a wounded stag. I do not gather, though I know the root that opens the mind and the mushroom that closes it. My task is to walk between. I sit by the fire and listen to its stories. I watch the flicker of flames and see the shapes of things to come.

When the clan prepares to move, they ask me to dream. When someone dies, they ask me to speak their name to the sky. When the children cry in the night, they come to me, and I mark their brows with soot and tell them the spirit of the river watches over them.

I do not command. I do not rule. I remind. I connect. I carry the breath of the past into the present.

The Spirits in All Things

To me, the world is not dead. The wind listens. The stones remember. The fire sings. Even the silence between footfalls has a voice. The animals do not just live—they teach. The raven speaks riddles. The bear brings power. The deer shows gentleness.

I teach the young ones that we are not above the world. We are inside it. Like marrow inside bone, or breath within lungs. The mistake is to think we own the land, or that death is the end. Nothing ends. It only changes shape.

The Walls That Speak

Sometimes, I paint. Not for beauty, but for memory. I mix red ochre, black soot, white chalk, and yellow clay. My fingers remember dreams better than my tongue. I paint the shape of the great hunt, the eyes of the snow cat, the hand of the child who did not return. The walls are our storybook. They are where we speak to the ones not yet born.

Tika helps me sometimes. He is clever. His hands are restless like mine were once. He paints with energy. I paint with stillness. Together, we make the future and the past meet in color.

A Life Between Moments

I do not know how long I will be the Dreamwalker. The spirits do not tell me everything. Sometimes they are quiet, and I must learn to wait. Sometimes they shout, and I must choose whether to listen.

I have no children of my own, but I have many children in spirit. I leave behind not flesh, but stories, symbols, songs. I will be remembered not for what I did, but for what I helped others see.

The Dream Continues

One day, when my bones rest in the earth, I hope they will say this of me: Maku walked the edge of the firelight. He saw what others could not. He spoke softly and listened deeply. He reminded us that we are not alone in this world.

For in the Paleolithic world, the dream is just as real as the hunt. The unseen shapes the seen. And the spirit, like the wind, leaves its mark even when it cannot be held.

The Walls Remember: Cave Art and Early Symbolism – Told by Maku

I first pressed my hand to stone when I was very young. It was deep in a cave where the fire’s light barely reached and the air was thick with dust and breath. My fingers were covered in red ochre, and I held my hand steady against the rock. Then, with a mouthful of pigment, I blew around it. When I pulled my hand away, the mark remained—bright, alive, and larger than me. That was the first time I realized something sacred: stone could remember.

Since then, I’ve left many handprints. Not just mine, but those of others—children, hunters, mothers. Each one says, I was here. But it also says something more: We are together. A handprint is not only a mark of being. It is a connection across time, a silent greeting to those who will come after.

The Spirit of the Beast

You’ve seen the animals—painted in charcoal and ochre, in sweeping shapes along the cave walls. Bison with curved horns, horses with flared nostrils, mammoths heavy with age and wisdom. I’ve painted many of them, but never with the intention to simply show them. No, we paint what we dream. We paint what we honor. These are not just animals—they are spirits, guides, forces that walk with us even when they are not near.

When we prepare for the hunt, I often paint the animal before we leave. Not as a way to boast, but as a way to call its spirit. We show it respect. We ask for its strength. Sometimes the hunters will touch the painted form with their fingers, whisper to it, or offer it a bit of dried meat before they go. It is not magic. It is memory made sacred.

Marks That Mean More

Not all marks are creatures. Some are spirals. Some are dots in rows. Some are zigzags or concentric circles. The children ask me what they mean. I tell them, “That is the storm that never came. That is the path of the elk herd five winters ago. That one is the song my mother sang before she left her body behind.”

Symbols are the bones of our stories. They hold meaning we cannot always say out loud. They are not just for beauty. They are for memory. They hold what words forget.

Sometimes I add a mark after a dream. Sometimes after a death. Sometimes I paint in silence, not knowing why until later. The spirits speak in many ways, and I have learned not to ask too many questions when they do.

Telling Without Speaking

There are children in the clan who cannot speak. There are elders who have forgotten names. But when they look at the walls, they understand. They touch the painted stories and smile. They hum a tune that matches the brushstrokes. They remember what it means to belong.

That is why we paint—not just to tell others, but to tell ourselves. When we are afraid, the cave holds us. When we are lost, the art shows us where we’ve been. It is our map, our song, our storybook. It tells of births, hunts, storms, and visions. It tells of love. It tells of sorrow.

The Ritual of Painting

I do not paint alone. Often, others help. Tika brings me fresh pigment—red from crushed rock, black from burnt wood, yellow from clay. Omu blesses the spot before I begin, murmuring thanks to the earth. Sometimes the hunters gather, watching, silent as I paint the beast they seek. The fire flickers, and the shadows move with the paint, making the wall come alive.

Before I begin, I sit. I breathe. I listen to the stone. Not every wall wants to hold a story. Some echo cold. Others sing when touched. When I find the right one, I begin, slowly. My fingers know what to do.

More Than We Seem

We are not just creatures of bone and blood. We are story. We are memory. We are meaning. The cave walls prove it. No beast leaves a message in red ochre. No bird paints its wings in charcoal. But we do. We reach beyond ourselves. We stretch into the unseen.

In the Paleolithic world, the cave is more than shelter. It is the place where spirit meets stone. Where dream meets hand. Where silence speaks.

And when I am gone, long after my fire has died, I know someone will walk into that cave, place their hand in the same spot I did, and say, without words, I remember.

The Breath Beyond Breath: Spiritual Life and Rituals – Told by Maku

When I was very young, I asked my grandmother where people go when they die. She looked at me, long and quiet, and said, “They go back to the breath of the world.” I did not understand then. But now, I have seen the breath leave many mouths—young and old, hunter and child—and I have felt that breath move through the air long after the body is still. Death is not the end. It is the turning of a circle. This is what I have come to know.

I am called Dreamwalker, not because I sleep often, but because I listen to what is spoken in silence. The spirits do not shout. They whisper. And if you are quiet enough, they will tell you where the lost ones walk.

Burial Beneath the Earth

When someone dies, we do not burn them. We give them back to the ground. We dig a deep place—near the river, in the hills, or sometimes inside a cave if the spirit prefers stone. We wrap them in hide, place with them a tool or token—something they touched often, something they might need on the path beyond. A spear for a hunter. A carved bead for a child. A bowl for one who gathered.

We paint the face with ochre, red like the first fire. Red like blood. It is a color of life, but also of return. Then we speak their name, not loudly, but gently, as if we are placing it into the wind. Omu sings. I speak to the sky. We cover the body with earth and stones, but the spirit rises. Always rises.

Afterward, we sit together in silence. We share food. We tell stories. We speak of what the person did, what they loved, what they feared. And we laugh. The dead do not like to be mourned with only tears. They lived. That is worth remembering with joy.

The Spirits That Walk Among Us

We do not believe that the world is made only of things we can see. The world is full of spirit. The wind has voice. The fire has mood. The animals dream and speak to us, even if their mouths do not move. The bison carries strength, the owl brings warning, the wolf teaches loyalty. When we see them in the waking world, we learn from their movement. When we see them in dreams, we listen even closer.

Once, I dreamed of a bear with white fur. The next day, a storm came and flooded the valley. I had told Sena to move the camp higher, and he listened. I do not claim to control the storm, but the spirits had given warning. That is their way. They speak in signs, not commands.

Even the rocks hold spirit. Some glow when touched. Some feel warm though the sun has left. We do not carve every stone. Some are left as they are, sacred and watching. When we sit by a special place—like the painted cave walls—we speak softly. The spirits are always listening.

The Ancestors Still Watch

Our ancestors do not leave us. Their bodies may rest beneath earth, but their voices rise with the wind, and their thoughts live inside us. Sometimes when I hum, I hear the melody of my grandmother’s voice. When I walk the old paths, I feel her feet beside mine.

Children are born with old souls sometimes. Tika, I believe, carries the eyes of a maker from long ago. He sees beyond tools. He sees into things. When he speaks to the fire, I hear an echo of someone who lived before even Omu’s time.

We honor the ancestors with food offerings, with whispered stories, with silence. When we eat the first berries of the season, we leave some beneath a tree. When the moon is full and the fire high, we dance their names into the night. They do not ask for much—only that we remember.

The Role of the Dream

Dreams are not empty. They are not tricks of sleep. They are the place between places. I do not know why some dreams speak true and others fade, but I know that when I see the same image more than once, I listen. When someone comes to me saying they dreamed of their mother’s face in a fire, I sit with them. We talk. We watch the flames. And often, we find the message hidden in the glow.

Some fear dreams. I do not. I believe they are gifts—heavy gifts, yes, but gifts nonetheless. They guide. They warn. They heal.

Living in a World of Spirit

In the Paleolithic world, nothing is without meaning. The stone, the stream, the wind, the creature that walks past the cave mouth—they all carry spirit. And so do we. We walk with ancestors behind us, spirits beside us, and dreams ahead.

When I speak to the fire, I am not just talking to myself. I am speaking to everything that came before me, and everything that will come after. I am a voice in the long song of the world.

And when I leave this world, I will join the wind. I will rest in the roots. I will whisper in the dreams of those who still walk. Because the spirit never ends. It only changes shape.

Web That Holds Us Together: Community Roles and Cooperation – Told by Omu

People think strength is in the spear, in the chase, in the fire that roars. But I have lived long, and I know this: true strength is in the bond between us. We are not beasts who walk alone. We are a people—a circle, woven like the baskets I carry. Every strand matters. Every hand plays a part. And when one hand fails, we all feel the break.

When I was young, I believed that only the fastest mattered—the strongest, the boldest, the ones who brought down the bison. But it was my grandmother who taught me to see more. She said, “The spear feeds, but the hand that cooks, the one that heals, the one that sings when the dark comes—that hand saves lives too.”

Roles Chosen by Wisdom, Not Rule

We do not place people in roles by force. We watch. We listen. We learn what each person is good at, and we honor that skill. A small child with quiet feet may one day be the best tracker. A boy with a gentle voice may be the one who soothes a dying elder. A girl who climbs trees like wind may be the first to spot berries no one else can reach.

Tika, full of energy and fire, was never strong enough to carry a kill. But give him stone and spark, and he’ll invent something no one else dreamed. Sena, though fierce in the hunt, listens before he speaks. That is why we follow him. Maku sees what others miss. So we trust him with our dreams.

Old ones like me—we carry memory. We don’t run anymore. We guide. We teach. We sing the stories into the firelight so they won’t be forgotten.

Strength Comes in Many Forms

Strength is not only in muscle. It is in hands that weave tight, in feet that move steady, in backs that carry the sick without complaint. When someone is hurt, it is not only the hunter who matters. It is the one who chews bark into medicine. It is the one who gathers wood for warmth. It is the one who holds the child until the crying stops.

We do not say, “You are man, so you do this,” or “You are woman, so you do that.” We say, “You are skilled. Show us what you can do.” There are women who hunt better than many men. There are men who raise children with hands as soft as mine. What matters is the care, the contribution, the heart behind the task.

The Circle of Work

In the morning, the camp stirs together. Some go to gather. Some prepare tools. Some tend the fire or teach the young. No one is idle unless they are ill or grieving. And when they are, we carry their weight. We cook their meals. We bring them water. Because we know—tomorrow, it could be us in need.

Even the children work. They carry kindling. They fetch water. They listen to the stories, learning when to laugh, when to sit still. This is how they grow into their roles—not by age alone, but by watching, helping, becoming.

When We Walk, We Walk Together

When we migrate, it is not one person’s burden. We pack as a family. The strong carry more. The weak carry less. But all carry something. Even the oldest among us tie a pouch to their belt, full of herbs or stones or memory.

We take turns watching the fire, guarding the food, carrying the youngest. No one is forgotten. No one is left behind. If a leg breaks, we build a litter. If a heart breaks, we sit in silence and let it mend.

To Survive Is to Share

Without cooperation, we would not last a season. The world is too harsh. The cold too deep. The beasts too strong. But together, we find warmth. Together, we find the trail. Together, we share what we have, and no one goes hungry while another feasts.

In the Paleolithic world, survival is not about the loudest voice or the sharpest spear. It is about the quiet strength of many hands working as one. That is what I teach. That is what I have seen. That is what I know.

And as long as the fire burns and the stories are told, our people will endure—because we do not stand alone. We stand together. Always.

Night of Firelight and Voices: Oral Tradition and Storytelling – Told by All Together

The hunt had gone well, and the air was thick with the smell of roasted meat. Children laughed between bites, and the elders sat near the fire, backs straight, eyes watching. As the last of the bones were tossed into the flames, Sena stood and looked across the circle. The wind was still. The fire crackled softly.

“It’s time,” he said, his voice low and steady.

Tika grinned, already gathering sticks and stones for props. Maku sat cross-legged near the fire’s heart, tracing a spiral into the dust. I, Omu, settled onto my mat of woven grass, my hands resting in my lap, ready to speak when it was time.

This was our tradition. Not just food, not just fire—but story. The binding of all that we are.

Omu Speaks: The Memory of the Old

I have seen many moons rise and fall. Faces have changed, bones have returned to the soil, but the stories remain. That is how we live beyond our bodies. I speak first tonight, not because I know more, but because I remember those who came before us.

When I was a girl, my grandmother told me of the flood that swallowed the forest. Of how the birds flew inland days before, and how her father watched the ants build their mounds higher than ever before. “The world speaks before it moves,” she told me. And now, I tell that story to every child who listens. So when they see the birds take wing without a sound, they know to prepare.

Stories are not just for delight. They are our memory. They warn. They teach. They keep the dead alive.

Maku Speaks: Dreams in Movement

Stories are not only spoken. They are danced. Sung. Drawn into the earth with fingers or painted on cave walls. When I dream of the wolf spirit that walks between the worlds, I do not just say the dream. I howl it. I move like him. I drag my shadow along the rock face and leave a streak of ash behind.

We paint the great hunt with ochre and charcoal. But around the fire, we become the bison. We stomp and snort and charge. The young ones learn not only what happened—but what it felt like. What it meant.

I have seen Tika leap across the fire, howling like a jackal to tell the story of the time the moon disappeared. His body speaks louder than words. That is the power of story—when you feel it in your bones.

Tika Speaks: The Fire of the Young

I don’t remember every lesson Omu taught me. I wish I did. But I remember the stories. I remember her voice when she told of the girl who touched the sun and returned with gold in her eyes. I remember pretending to be the boy who tricked the river spirits by walking backward through the reeds.

When I tell stories, I move. I jump. I sing. I use stones as animals and sticks as spears. The little ones sit wide-eyed, not blinking. And when they sleep, I hear them whispering parts of the story to themselves.

That’s how we remember. Not by keeping the words still, but by breathing them. By living them again and again.

Sena Speaks: The Truth in the Telling

When I was a boy, my father told me of the bear that would not die. It stalked the hunters for days, and only when they sang to it—offering respect—did it finally fall. I asked him if the story was true. He said, “Every word, and none of it.”

Stories are not always fact. But they carry truth. They teach us what is dangerous, what is sacred, what is foolish, and what is wise. I’ve seen young hunters make mistakes—then stop, mid-step, because they remembered a story. They remembered how the fool in the tale stepped too close to the cliff, or how the clever one listened to the wind before chasing prey.

A good story is sharper than any spear. It stays with you longer than any wound.

Together: The Song of the People

And so we speak. We sing. We dance. We mimic voices. We act with our hands and our eyes. Because without stories, the knowledge dies with the body. Without stories, the children grow without roots.

Every story we tell is a path back home. Every tale is a spark carried forward.

In the Paleolithic world, the fire may warm the flesh—but the story warms the soul. And as long as we tell them, as long as the fire still burns, we are never lost.

Beside the Fire, Beneath the Stars: The First Migrations Out of Africa – Discussed by Sena and Tika

The fire had burned low, casting long shadows against the cave walls. Most of the clan had drifted to sleep, but Tika sat beside me, his fingers playing with a bone carving, eyes still wide with the energy of a restless mind. I, Sena, stared into the coals, remembering a story that had been passed to me not through words, but through footsteps—long and ancient. A story of movement. Of leaving. Of becoming.

“You ever think,” Tika said, voice quiet, “about the first ones? The first ones who walked out into the unknown?”

I looked over at him, the firelight flickering across his young face. “Every time I follow a trail I’ve never seen before.”

The Long Walk Begins

The story begins in the heart of Africa. Not in our time—but far, far before. When the rains fed great green valleys, and the sky sang with birds whose names no one speaks anymore. That was where our oldest ancestors lived—beneath trees, beside rivers, walking upright with fire in their eyes.

“They didn’t leave all at once,” I said, stirring the coals. “The land changed. The rains pulled away. The trees thinned. The animals moved. So they followed.”

“Like we follow the mammoths,” Tika said.

I nodded. “Exactly. Not because they wanted to conquer new places. But because they had to eat. To live.”

Crossing the Threshold

“They crossed into the north,” I continued, “through narrow valleys and dry stone passes, their feet calloused, their arms cradling children and bundles of flint. The first to leave Africa didn’t know what lay ahead. But still, they walked.”

Tika leaned in, eager. “What did they see?”

I smiled. “New things. Terrible and beautiful. Lions that hunted at night and snakes longer than a man. Forests so thick the sun barely touched the ground. Ice, later. Cold that bit into their bones. And animals they had never imagined—giant elk with crowns of antlers, shaggy beasts with curled horns, saber-toothed cats waiting in the snow.”

Tika’s mouth twisted in a grin. “And they didn’t run back?”

“They didn’t even know how far back was. They just kept walking.”

New Lands, New People

From Africa they spread into what we now call the Middle World—Eurasia. Some followed the coastlines, fishing and foraging where the water met the land. Others wandered inland, over mountains and through deserts. Each group faced its own challenges—cold winters, predators, strange plants that poisoned the unwary.

“They had to learn fast,” I said. “New tools, new shelters, new ways of tracking. What worked in the warm forests didn’t work on the wind-blasted plains.”

Tika added, “They probably made new stories, too. About the beasts with glowing eyes, the mountains that growled in the night.”

I nodded. “And they remembered. Passed those stories down. Like we do.”

To the Ends of the Earth

“Some of them crossed the land bridge to a world no one had ever seen,” I said, my eyes drifting beyond the fire. “Across the ice, over into the farthest reaches—what we now call the Americas. Imagine that, Tika. Looking across frozen sea and deciding to walk anyway.”

He shivered despite the fire. “Why would they do that?”

“Because they were searching for food. For space. Or maybe they were just following the stars. Some people are born with restless feet.”

Tika smiled. “Like me.”

I laughed. “Yes, like you.”

The Price of the Journey

“Not all made it,” I said, my voice softening. “Some froze. Some starved. Some disappeared into forests that swallowed them whole. But many did make it. And with each step, they became something new.”

Tika tossed a twig into the fire. “So we carry them. All of them. Their walks, their fights, their dreams.”

“Yes,” I said. “In our feet. In our hands. In the way we make tools and speak stories and track animals across rivers.”

Still Moving Forward

We sat in silence a while, watching the flames dance.

“They were brave,” Tika finally said.

“They were us,” I replied. “And we are them.”

In the Paleolithic world, to move is not to wander. It is to survive, to grow, to change. The first migrations out of Africa were not escapes. They were beginnings. And every step we take now—across river, across plain, across time—is a step on that same path. The path of becoming human.

The Role of Women in Paleolithic Societies – Told by Omu and Sena

The sun had nearly slipped behind the ridge when Sena returned with the hunters. The air smelled of blood and pine—signs of a good hunt. I, Omu, was kneeling by the fire, grinding dried herbs with a flat stone, when he sat beside me, laying his spear across his knees. His eyes were tired, but there was something thoughtful behind them.

“You know,” he said after a long silence, “some say the women only gather and raise children.”

I didn’t look up. “Some say that. But they weren’t there when I pulled my own daughter out of a pit full of thorns while her brothers waited for someone else to act.”

He chuckled, rubbing his hands. “I know. I’ve seen it too. But not everyone wants to remember.”

Not Just Baskets and Babies

In my youth, I climbed trees higher than any boy in my band. I knew which birds guarded their nests and which vines could support my weight. I chased wild goats until my legs bled. And yes—I hunted. Not every day, but often enough. There was no rule that said I couldn’t throw a spear or set a trap.

The truth is, women do what they’re able to do. Some are quick and quiet enough to track a deer. Others have hands built for weaving tight baskets or crafting tools so fine even Tika stares in awe. It was never about woman or man. It was about who could do the task, who had the spirit for it.

Sena nodded. “In the last hunt, we followed a boar into a thicket. It circled back, came at us from behind. It was Dena—the youngest girl in our group—who dropped it with a perfect throw. If she hadn’t, we’d be nursing broken ribs.”

Who Leads the Spirit?

Sena glanced over to where Maku sat in stillness, his eyes closed, speaking softly into the wind. “They say only men can be spirit walkers. That’s not true either, is it?”

I shook my head. “The best dreamer I ever knew was my aunt. She painted symbols before she could speak. She led rituals when her hair was still black as night. People followed her because she saw things others could not. Maku follows in her footsteps.”

There have always been women who see beyond the veil. Women who dream, who heal, who bless the dead and name the living. Some carry fire. Some carry herbs. Some carry silence and the wisdom inside it. The spirits do not care about gender. Only about the weight of a person’s heart.

Age, Skill, and the Way of the Camp

Sena picked up a twig and began to draw in the dirt. “So why do some still think in parts? Men do this. Women do that.”

“Because it’s easier,” I said. “Simple rules comfort simple minds. But life is not simple. Not when you’re cold, hungry, and chased by a beast. Then you stop asking who’s supposed to do what. You ask who can do it.”

We divide tasks by age, skill, and need. The youngest learn by watching. The swift hunt. The wise teach. The patient care for the sick. If a man knows how to wrap a broken ankle, we don’t turn him away from the healer’s fire. If a woman can run all day and strike like lightning, we don’t keep her from the hunt.

Stories That Forgot the Women

Later, by firelight, I told the children of Lura, the spear-thrower who once brought down an elk alone. Of Nali, who led the crossing of the frozen river when the men hesitated. Of Yaya, who kept the fire burning through the winter storms when others had given up.

Sena sat beside me and added his own memories. He spoke of Mira, who taught him how to follow tracks in soft moss. Of elder Na, who pulled him from the river when he slipped during a crossing. “They say men lead the hunt,” he told the children, “but I’ve followed women who walked straighter and saw farther than I ever could.”

Comments